Starting in 2007, Dr. Daniel Budnitz, a scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medication Safety Program, began tracking an obscure but unsettling statistic about children’s health.

Each year, more and more kids were being rushed to emergency rooms after swallowing potentially toxic doses of medication. By 2011, federal estimates put the figure at about 74,000, eclipsing the number of kids under six sent to ERs from car crashes.

In most cases, children experienced no lasting harm from accidentally ingesting pills or liquids from the family medicine cabinet, but about one in five had to be hospitalized for further evaluation. About 20 children died each year from such accidents, CDC data showed.

As an epidemiologist and the father of two kids, including one who had a penchant for putting things in his mouth, Budnitz became fixated on reducing drug overdoses.

In particular, he saw an easy solution for the roughly 10,000 emergency room visits a year involving liquids, such as over-the-counter pain relievers and prescription cough syrups.

It was a type of safety valve called a flow restrictor. The small plastic device fits into the neck of a medicine bottle and slows the release of fluid, providing a backup if caregivers leave child-resistant caps unfastened or kids pry them off.

In 2008, Budnitz persuaded drug makers, federal regulators, and poison experts to come together on an initiative to add flow restrictors, which cost pennies apiece, to medicine bottles.

Today, however, that promise to make medicine safer for kids remains largely unfulfilled, hindered by industry cost concerns and inaction by federal regulators, an examination by ProPublica found.

Honoring a pledge made in 2011, drug makers have added restrictors to infants’ and children’s acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol. That year, roughly one-quarter of kids’ ER visits for drug accidents involved pediatric or adult formulations of acetaminophen.

But the industry has neither promised nor delivered such protection on other medicines, which account for more than half of kids’ ER visits stemming from drug accidents, including antihistamines, ibuprofen, and cough and cold preparations. ProPublica purchased more than 50 pediatric versions of these products marketed by nine different brands at outlets in California, New York, and Washington, D.C. None of the products we bought had flow restrictors.

In some instances, companies that have placed flow restrictors on acetaminophen-only kids’ products have not put them on bottles of pediatric cough and cold syrup that contain the same amount of acetaminophen.

“If flow restrictors work, they should be placed on all liquid products,” said Dr. G. Randall Bond, a pediatrician and poison expert who has consulted with drug makers. “We need a technological change to get us to the next level of safety.”

Industry officials said that they were waiting for better data to quantify the extent to which restrictors mitigate kids’ risk from drug accidents before deciding whether to add the devices to more medicines.

“We will continue to evaluate whether other initiatives or interventions make sense,” said Barbara Kochanowski, the vice president of regulatory and scientific affairs at the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, an industry trade group for over-the-counter drug companies.

Industry leader McNeil Consumer Healthcare, the Johnson & Johnson unit that makes Tylenol, said it was committed to child safety, but said flow restrictors were only one part of the solution.

“We believe the first line of defense against accidental unsupervised ingestion is secure storage and immediately returning medicines to a high and out-of-sight location following each and every time the product is used,” the company said in a statement.

Makers of liquid acetaminophen started to add flow restrictors in 2011 and, in the absence of any government or industry standards, companies rolled out a variety of designs.

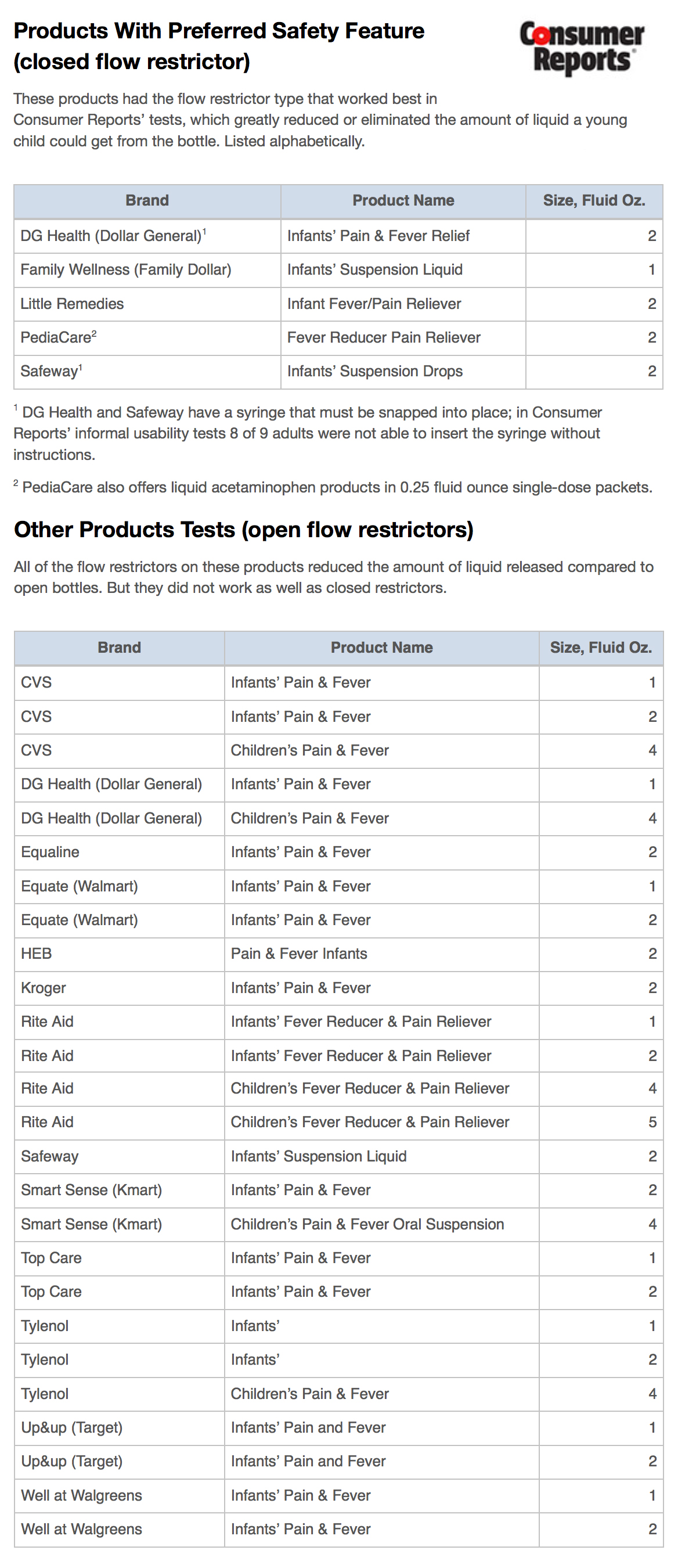

To gauge their effectiveness, Consumer Reports—an independent, non-profit testing organization—tested the devices found on 31 different products, duplicating the ways a child was most likely to squeeze, shake, or suck medicine from the bottle. The results, which were shared with ProPublica, confirmed that all models of flow restrictor reduced the amount of liquid that escaped under these conditions—an outcome Consumer Reports lauded.

This is critical with acetaminophen. While generally safe if taken as recommended, the drug can cause liver damage and death if taken in larger amounts. As ProPublica has reported, about 150 Americans die each year after accidentally overdosing on acetaminophen, and tens of thousands more are hospitalized, the vast majority of them adults.

But some of the restrictors used on bottles of liquid acetaminophen work better than others, Consumer Reports found. Bottles with so-called closed restrictors—covers with small holes that open when punctured by a syringe then reseal when it’s removed—outperformed those with open restrictors, hard plastic discs with holes that do not reseal.

PediaCare and store-brand acetaminophen from Safeway, Dollar General, and Family Dollar used the better-performing restrictor, tests showed. Many other store brands did not. Consumer Reports also found that McNeil, a company that has long promoted the safety of its products, does not use the “more effective” design. None of McNeil’s products were placed in the “preferred safety feature” category.

Consumer Reports and ProPublica contacted McNeil with questions about the test results. The company would not directly address why it has chosen a less effective flow restrictor. McNeil pointed to a recent study that showed 94 percent of kids tested were unable to empty an uncapped bottle within 10 minutes if it used any design of flow restrictor.

“The issue of accidental ingestion of medicine by young children is one we take very seriously,” said the company, which provided information on its product specifications for the study. “Each manufacturer makes its own decisions about safety designs that work best with its bottles and existing manufacturing process.”

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission has the power to set standards for flow restriction but, by law, must start by working toward voluntary guidelines. Though commission officials have participated in Budnitz’s initiative for years, the agency never instigated the standard-making process.

Instead, Budnitz did so. In early 2013, he contacted ASTM International, a leading standard-setting body.

“It is an active process that’s moving in a positive direction,” said Scott Wolfson, a spokesman for the CPSC. (Commission officials serve on the ASTM committee that is considering flow-restrictor standards.)

Officials with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which oversees drug safety, have long voiced support for flow restrictors, publicly urging companies to use them.

“Tens of thousands of children still overdose each year, and yet the technology used to prevent accidental ingestion has hardly changed for decades,” FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg told pharmaceutical company executives at an over-the-counter drug conference in Florida in 2010. “New tools—such as single-dose packs and flow restrictors—must be explored for their potential to prevent unnecessary suffering.”

But the FDA has not moved to require the devices; agency officials have offered differing opinions as to whether it has the power to do so. In a statement to ProPublica, the FDA said it “encourages companies to continuously improve the safety of their products and encourages discussions with manufacturers on measures that will help in this regard.”

The hands-off approach of the FDA and CPSC has left it largely to Budnitz to continue the campaign for flow restrictors. Trim and balding, with an abhorrence of confrontation, he has doggedly pressed forward, even though his own agency, the CDC, has no funding for his initiative and no regulatory authority over the products he is determined to make safer.

“This could be a win for everyone,” he said. “No one wants kids to be harmed.”

FOR PUBLIC HEALTH EXPERTS, the recent rise in pediatric drug accidents was an unexpected development.

Child poisonings, of which drug accidents are a subset, had been falling since the 1970s, when manufacturers introduced child-resistant caps. Poisoning deaths among children (PDF) had dropped from more than 200 a year in 1972 to 28 by 2000.

But over the next decade, Budnitz and others saw the total number of childhood accidents start heading back up, though poisoning deaths held relatively constant.

Budnitz analyzed federal data based on a sample from about 60 emergency rooms to generate an estimate of how many children were taken to ERs nationwide each year after drug accidents. He found that ER visits jumped by about 32 percent between 2004 and 2011. (Budnitz is studying the data more closely to determine if the increase is statistically significant and not the result of chance.)

Similarly, a 2012 study co-authored by G. Randall Bond, based on data from the American Association of Poison Control Centers, found that the number of children evaluated at health care facilities for drug overdoses increased sharply between 2001 and 2008. The preponderance of cases involved children getting into drugs unsupervised.

Both Budnitz and Bond found evidence that at least some accidental ingestions result in harm.

Budnitz’s analysis showed that in 2011 about 15,000 of the 74,000 children who went to the emergency room after a drug accident were admitted for further evaluation or treatment.

The poison control center data showed that of 450,000 children evaluated, more than 25,000 exhibited symptoms ranging from a faster heart rate to brief seizures to liver damage, a life-threatening condition.

Even in cases in which children suffer no ill effects, pediatric drug accidents have other costs, from the anxiety experienced by panicked parents to the expense of unnecessary trips to the ER, medical experts said.

Researchers suggest the increase in drug accidents might be tied to several factors, including that families have more, and more powerful, medicines in their homes. Most of the accidents involved pills, such as painkillers.

Though fewer accidents involved liquids, Budnitz focused on them because—inspired by automakers, which improved safety with seatbelts, improved car frames, and airbags—he thought it might be possible to make medicine bottles safer with better engineering.

He started Googling for ideas and came across an ad for flow restrictors.

The devices had mostly been used on prescription medications as a way to improve dosing accuracy. By sticking a syringe into a small opening, or self-sealing cap, a person could withdraw the exact amount of medicine required instead of relying on a teaspoon or cup.

Budnitz thought the devices could help with safety, too, slowing the flow of medicine and making it more difficult for a child to ingest a dangerous amount.

In 2008, when the Consumer Healthcare Products Association approached him for help with a campaign to teach parents to administer cold and cough medicines properly, Budnitz had a counterproposal: Gather officials from industry, government, and science to discuss safer packaging.

“I didn’t want to publish a paper just to publish a paper,” he said. “I wanted to do something.”

These groups were unlikely candidates to join forces—they often took opposite sides on regulatory matters.

But then Budnitz found an influential ally: Dr. Edwin Kuffner, the medical director of McNeil, whose flagship brand, Tylenol, had long been the market leader in over-the-counter pain relievers.

“It’s hard to move the industry,” Budnitz said. But “Kuffner said, ‘I want to make this happen.'” (Kuffner declined comment, referring questions to McNeil’s corporate spokeswoman.)

Thus was born what came to be known as the Preventing Overdoses and Treatment Errors in Children Taskforce—the PROTECT Initiative.

IN SOME WAYS, KUFFNER’S backing reflected McNeil’s history.

The company’s very first product was a liquid medication for children called Tylenol Elixir. From that, McNeil built Tylenol into a billion-dollar brand, principally by marketing its safety. The company was often an innovator on this front, developing tamper-proof pills and spending millions to help fund poison control centers and develop an antidote to acetaminophen poisoning.

Still, over time, regulators and researchers became increasingly concerned with the drug’s risks. In the mid-1990s, the FDA raised questions about the safety of acetaminophen for children.

In 1999, McNeil launched an early experiment in flow restriction, introducing a new cap for Infants’ Tylenol called the SAFE-TY-LOCK.

A dropper was slotted into a hole at the top of the bottle. Even with the dropper gone, the liquid would drip out through the hole slowly, reducing the chance that a child could swallow a toxic dose.

Anthony Temple, McNeil’s longtime medical director and Kuffner’s predecessor in that position, later testified at a trial that McNeil had a patent on SAFE-TY-LOCK, but the company offered to give it away to generic competitors to make all acetaminophen products safer.

Though generic drug makers often follow McNeil’s lead, few, if any, added SAFE-TY-LOCK.

Still, there were early signs that the device could make a difference. In 2002, McNeil provided the FDA with a company analysis showing that the number of consumer calls about mistakes made in dosing infants had “declined notably” since SAFE-TY-LOCK’s introduction. In a later presentation, Kuffner included a slide that said “flow restrictors will reduce accidental unsupervised ingestion for infants’ concentrated drops.”

McNeil stuck with its restrictor design even as other, more advanced models became available.

Dr. Abner Levy, an inventor and the president of Los Angeles-based Andwin Corp., had developed a resealing restrictor after having a frightening experience while babysitting his granddaughter. He’d taken the cap off a bottle of medicine, then left it to answer the phone. When he turned around, he saw the little girl had managed to drink some of the liquid. It wasn’t enough to harm her, but it could have been, he realized.

“I imagined, ‘What if she had drank the whole bottle?'” said Levy, now 85. “She was absolutely in danger of her life.”

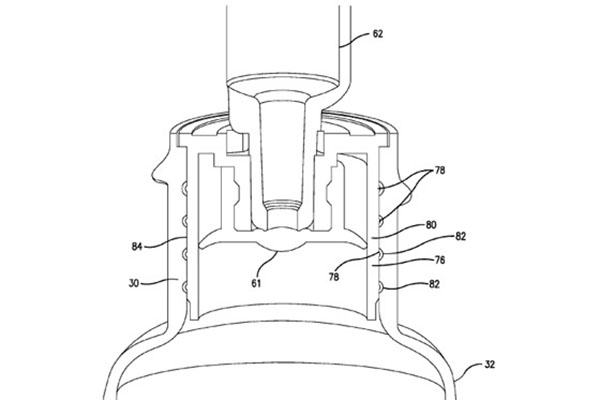

Levy’s flow restrictor allowed users to withdraw medicine by poking a syringe through an opaque, flexible protective seal over the bottle’s opening; when the syringe was withdrawn, the rubber would reseal.

In February 2008, he visited McNeil’s headquarters in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, hoping to persuade the company to buy his invention. The pitch seemed to go well enough, he recalled, but follow-up conversations went nowhere.

McNeil did not respond to questions about its dealings with Andwin.

Andwin received a similar response from most other drug makers. In the end, it managed to persuade only one company to use its restrictor: Prestige Brands, which makes PediaCare and Little Remedies.

“Even though you can show that it can help save lives, the pharmaceutical companies are looking at the bottom line,” said Ryan Smith, Andwin’s general manager.

“Change is driven by consumers or requirements set by the federal government,” he added. “Nobody wanted to be the first to do it.”

The experience left Levy bitterly disappointed.

“I have a belief: If you gain an understanding of a problem, then automatically you have a responsibility to fix the problem,” Levy said. “I had a responsibility to fix the problem.”

BUDNITZ CONVENED THE FIRST PROTECT meeting in November 2008 in a modern conference center with high windows at the CDC’s headquarters in Atlanta.

There were more than 30 participants, including executives from all the major over-the-counter drug manufacturers as well as experts in toxicology and public health. Bond, the pediatrician who later authored the 2012 study based on poison control center data, said attendees were initially wary.

“There were different perspectives on the size and causes of the problem, there were different ideas on the priorities for change and on which changes might work,” Bond said. “That made trust difficult.”

Flow restrictors were just one of three items on the agenda. Two initiatives rapidly gained support: a public-private educational campaign and a move to standardize bottle measurements.

Then Budnitz shared the eye-opening federal data on the rise of pediatric drug accidents and showed a slide about ketchup bottles, based on a Harvard Business Review case study.

Ketchup makers had moved from glass bottles that would not pour, to plastic containers that made an embarrassing noise when squeezed, to plastic bottles designed to be stored upside down to prevent noise and ensure an easy flow. If ketchup manufacturers could make a better bottle, why couldn’t the drug industry?

“I am not a packaging expert. I don’t know how production lines really work,” Budnitz recalled telling the group. “But I think there is something that can be better.”

Some drug makers voiced concern that consumers might resist packaging changes, especially if they had to use syringes instead of pouring liquid into cups.

Budnitz’s appeal resonated. One company, New Jersey-based Comar Inc., said it would begin work immediately to develop a safety valve for medicine bottles.

Momentum grew over the next few years. At one PROTECT meeting, Kuffner said McNeil was moving ahead with putting flow restrictors on its pediatric Tylenol products and was assessing specific design options, Budnitz recalled.

With the leading marketer of acetaminophen on board, the initiative had a place to start. Attention focused on the liquid forms of the drug and turned to the logistics of testing bottle designs and changing production lines.

But for McNeil, the linchpin of the push, this stage was complicated by a massive manufacturing disruption.

In April 2010, the company announced it was pulling 136 million children’s products from store shelves—the largest pediatric recall in history. The FDA had found minute traces of metal shavings and other contaminants during an inspection of the company’s manufacturing plants. The company was forced to shut down much of its production line.

Progress on flow restrictors didn’t resume until the following year, when it was nudged forward by the FDA scheduling a meeting of outside advisers on pediatric acetaminophen for May.

An analysis prepared for the meeting noted that 20 percent of 630 adverse medical reactions involving acetaminophen reported to the FDA over the course of a decade were the result of kids getting into medicine by mistake. The percentage was “alarming,” the analysis said.

A month before the meeting, McNeil announced it would put flow restrictors on Infants’ and Children’s Tylenol. A few weeks later, the industry group representing McNeil and other over-the-counter drug makers unveiled an agreement to do the same on all brands of pediatric acetaminophen.

“These enhancements are intended to help reduce the incidence and magnitude of accidental acetaminophen exposures in cases of unsupervised ingestions,” Kuffner said in a letter McNeil sent to health care professionals.

The companies made no public commitment to add safety valves to other liquid medications.

As it turned out, there was little pressure from federal regulators to do even as much as the industry had promised, let alone more.

FDA experts had recommended that manufacturers use flow restrictors, or similar barriers, to prevent accidental acetaminophen overdoses since at least 2001, according to a report obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. In 2011, in a summary of a decade’s worth of studies, the agency urged drug makers to investigate flow restrictors as among the measures “likely to have the greatest impact on patient safety.”

Yet when the FDA’s advisory committee met in May 2011, agency officials expressed caution about mandating flow restrictors and disagreed openly over whether they had the authority to require such a step.

Dr. Scott Furness, then director of the FDA division that regulates over-the-counter drugs, said they didn’t: “The short answer is, we cannot really make these restrictions,” he said.

Dr. Sandy Kweder, deputy director of the FDA’s Office of New Drugs, said the agency could set standards to slow the flow of medicine from bottles, but it shouldn’t do so, because establishing such regulations was so cumbersome.

“You have to remember, as has been pointed out adequately and then some, how long this process takes,” Kweder said. “The last thing we want is to be tied down.”

The advisory committee recommended that the agency look into whether drug makers should do what they’d already promised to do—use restrictors, or similar devices, on pediatric acetaminophen.

Two and a half years later, the FDA said it is studying the issue.

“These new strategies must be rigorously tested to show they work, and do so reliably,” the agency said in a statement. “The FDA believes the addition of accurate, well-tested flow restrictors should help make products safer by reducing the incidence of accidental pediatric ingestion.”

DRUG MAKERS STARTED INSTALLING flow restrictors on bottles of pediatric liquid acetaminophen later in 2011.

The devices were a small added expense, with basic models costing two to three cents apiece when purchased in bulk, manufacturers said. More advanced resealing designs cost eight to 10 cents apiece.

But companies also had to update production lines to put restrictors in bottles, said James Medford, until recently the owner and chief executive of Aaron Industries, which makes and packages acetaminophen for store brands. Medford said his company, which makes products that use both open and closed restrictors, invested more than $1 million on a new manufacturing line after the Consumer Healthcare Products Association announced the restrictor pact. (Aaron was recently purchased by PL Developments.)

These expenditures influence manufacturers’ decisions to expand the use of flow restrictors, Medford said.

“The next step is moving to other children’s products,” he said. “It’s going to be costly and time-consuming to do that.”

McNeil developed a restrictor system called SimpleMeasure. But in early 2012, it had to issue a recall for 574,000 bottles of Infants’ Tylenol that employed the system; some users had pushed the restrictor into the medicine bottle when applying pressure with the syringe.

When Infants’ Tylenol came back on the market in July 2013, McNeil chose to use older, open flow restrictors made by Comar, the company that began developing devices after the 2008 PROTECT meeting, rather than Comar’s newer resealing restrictor, which was advertised for sale earlier in the year.

In its statement, McNeil noted that each company had the freedom to pick a restrictor based on its manufacturing processes and bottle designs.

Walgreens and other store brands said they were using open restrictor designs in part because industry leader McNeil does so.

“Walgreens and its suppliers strive to offer products that are comparable to national brands. In this case, the national brand uses the earlier generation of flow-restrictor,” Walgreens spokesman Phil Caruso said in a statement.

When the drug companies announced they would install flow restrictors on pediatric acetaminophen products, they did not set a deadline. Manufacturers have deployed flow restrictors on infants’ acetaminophen, but some have not yet done so for children’s products, according to the Consumer Healthcare Products Association.

“While the vast majority of CHPA members’ children’s single ingredient products on the market also have incorporated the flow restrictors, some store brands of liquid children’s acetaminophen are in the process of the conversion now,” the organization said in a statement. “We understand that it should be another six to nine months until that happens.”

After completing its tests this fall, Consumer Reports recommended that drug makers both expand the use of restrictors to all adult and children’s liquid medications and switch to resealing flow restrictors.

McNeil said it was examining whether to use flow restrictors on its other pediatric medicines, such as Benadryl, an antihistamine, Sudafed PE, a decongestant, and Motrin, its brand with ibuprofen.

“McNeil continues to evaluate feedback and data on the effectiveness of flow restrictors and, based on the results of this data, will determine whether to extend the use of flow restrictors beyond Infants’ and Children’s TYLENOL,” the company said in a statement.

Those familiar with the industry said extending the use of the devices may be a tough sell, however, especially for store brands, which have less ability to pass on costs to consumers.

“Ultimately, it’s about making a profit,” said Clay Robinson, a packaging expert whose company tests safety devices for drug makers. “If it’s going to add cost, it’ll be hard to get industry interested.”

At the most recent PROTECT Initiative meeting in September 2013, Budnitz unveiled the 2011 pediatric drug accident data, charting another rise in ER visits.

The group agreed to continue working with ASTM International to develop voluntary standards for flow restrictors. (Consumer Reports has also joined the task group focused on this.) It remains unclear how long the process will take or how the Consumer Product Safety Commission will enforce them.

Budnitz—the doctor and the parent—wants to pick up the pace. His children are now nine and 12.

“I want to believe that before my kids have kids of their own, we will have made more progress to improve child safety packaging,” he said. He shook his head ruefully.

“More can be done. More can be done.”

This post originally appeared on ProPublica, a Pacific Standard partner site.