Ten years ago this month, Howard Dean burned his famous scream into the brains of American political junkies. It was the night of the Iowa Caucus on January 19, 2004. Dean was seeking to rally his supporters for the upcoming contests. He promised to be competitive in all of them, and then go to Washington, D.C., to win the White House, adding, for good measure, “Byaaaaah!” The collective recounting of this story is that the scream cost Dean the nomination. As Kenneth Walsh wrote in U.S. News & World Report, the scream “lives on as a case study of how a brief gaffe, given saturation coverage by the media, can cause deep damage to a politician’s image.” But is that accurate? A decade hence, this seems like a good opportunity to discuss whether the lesson we drew from this event is the right one. Two quick points:

1. Dean’s Support Was Crumbling Before the Scream

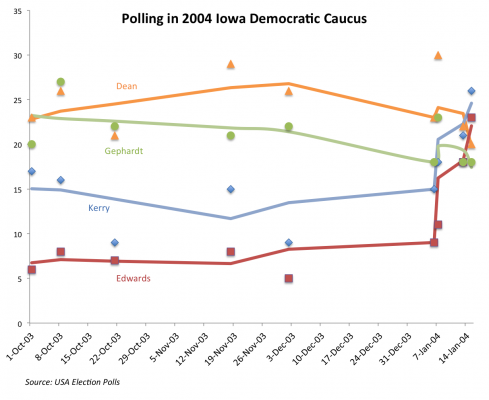

A feature of the scream that often goes unmentioned was that Dean was trying to energize his supporters after a loss. He had been the poll leader in the Iowa Caucus for months, as the graph below shows, but his support began to fade in the days before the contest, while the fortunes of John Kerry and John Edwards rose. There are a number of explanations for Dean’s fall, including a failure to be embraced by party insiders, an inability to convert online national support into on-the-ground organization, and an ad war with Richard Gephardt that pulled both of them down. But it’s key to remember that the Dean Scream occurred only after his disappointing finish in Iowa, the place where he’d concentrated most of his campaign efforts. A presidential candidate can certainly survive a third-place finish in Iowa, but it’s damaging to do so when you were widely expected to come in first and when you have little organization elsewhere.

2. Dean Was Unlikely to Win the Nomination Anyway

The winner of a presidential nomination contest tends to be the candidate with the most insider support, and Dean simply didn’t have that. He had generated the ability to raise money, largely with the help of the Internet, and he could make a lot of noise. But as Iowa demonstrated, he had a hard time translating that support into actual votes.

Sometimes, party insiders converge on a candidate long before the contests ever begin. That didn’t happen in 2004. A lot of Democratic governors and members of Congress waited to issue endorsements because they wanted to see how the candidates did in the early contests. Dean’s failure in Iowa demonstrated to them that he wasn’t a closer. (Contrast that experience with 2008’s Iowa Caucus, when Barack Obama demonstrated that a candidacy with celebrity-like appeal could actually translate hype into votes.)

Why didn’t insiders flock to Dean? Keep in mind the nature of his candidacy. He described himself as representing “the Democratic wing of the Democratic Party,” suggesting that others were not quite Democratic enough. He referred to the Democratic members of Congress who had voted with Republicans to support the Iraq War as “cockroaches.” He notably made enemies of many of the party elites. This is a terrific strategy to generate press but a terrible pathway to win a party’s nomination. Party insiders were far more impressed with John Kerry’s steady ability to generate votes and his longstanding party bona fides.

Why is it important to review these events from 10 years ago? Because myths generate their own reverence when repeated over time, causing us to learn the wrong lessons from history. The belief that Howard Dean would have been the Democratic nominee if he’d just given a calmer speech in Iowa ignores political realities and gives other candidates the wrong idea about how to succeed or fail in politics. And it contributes to the perverse conclusion that The Speech Is Everything. Ronald Reagan and John Kennedy gave important speeches against Soviet tyranny, but those speeches did not bring down the Berlin Wall. Barack Obama is a wonderful orator, but his exhortations have not ended racism, and no speech would have given us single-payer health care. Speeches can be beautiful and inspirational, but they rarely change our minds—we are actually much more discerning than we think.