It turns out, there’s a nice Halloween field experiment. Here’s the setup: On Halloween, a woman answers the door and invites the trick-or-treaters in. She tells them to “take one,” and then leaves the room leaving the bowl of candy and a bowl of nickels and pennies (adjusting for inflation: dimes and quarters, maybe even half-dollars). They did this experiment at 27 houses with a total of 1,300 kids.

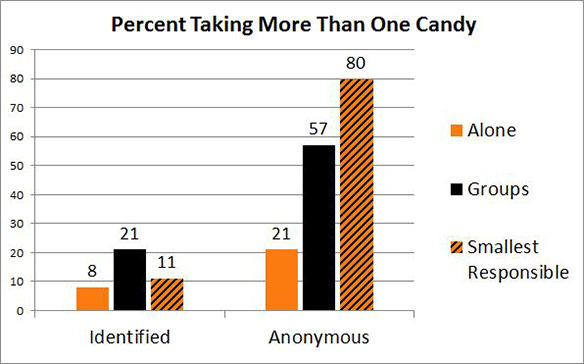

Overall, most kids (69 percent) took one. But conditions mattered.

In one experimental manipulation, the woman either asked the kids who they were and where they lived or she allowed them to be anonymous. Experimenters also noted whether the kids were trick-or-treating alone or in groups. For some groups, the woman designated the smallest kid in the group as being in charge of making sure that kids took only one. All these variables made a difference.

The greatest rate of cheating (80 percent) occurred when the smallest child was being responsible but everyone was anonymous. Diener reasoned that with responsibility shifted to the smallest link, the other kids would feel freer to break the rule.

Those who did cheat usually took only an additional one to three candies. But, of those who did grab more than what was offered, 20 percent took both candy and coins. Unfortunately, the Snickers study is not like the marshmallow study, so we don’t know where those greediest kids are now.

This post originally appeared onSociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.