There is a universe where the sole purpose of sports is to win or lose games. Players are judged only on their ability to add to a team’s chances of winning. Fans of the sports are well-versed in all of the different metrics that best determine how well individual players are performing. They also judge players based on how they perform, and not how they think they performed. Everything is straightforward, fans are courteous, and the discourse is levelheaded.

We do not inhabit that universe.

Instead, in our universe, there’s too much happening both on and beneath the surface in a single game for anyone to accurately understand it all without further examination. The purpose of sports is then … well, whatever you want it to be. Want to blow off steam by screaming at a 27-year-old who can’t always throw a football where you want it every Sunday? Sure! Want to try to find relatable bits and pieces of humanity throughout the 82-game season of a professional basketball team in Detroit? Yeah! Want to see human beings do things with their bodies that can only vaguely be described as “human?” OK! Want to consider the statistical implications of every action in a baseball game so you can further your understanding and therefore your enjoyment of that sport? Right on.

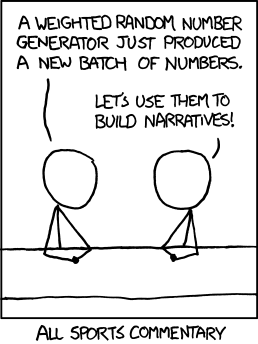

The point is: There’s a disconnect between why fans watch and why athletes play. A narrative gets built around players who, presumably, are just trying to win. Does this quarterback play worse when the game matters? Are that golfer’s personal problems affecting his backswing? Did that beautiful save by the goalie inspire his team to score two more goals and win? The answer’s almost always “no”—or way more complicated than simply “yes.” And still, on websites, in newspapers, on TV, and in our minds, the athletes often get cast into these roles that they don’t realize they’re playing. So, while it probably isn’t fair, is it possible for athletes to totally divorce themselves from the story built around them and just do their jobs as efficiently as possible? Or do they need to give in and try to find, fulfill, or create their own role in the stories we tell? Ryan O’Hanlon and Clint Irwin, a goalie for the Colorado Rapids of Major League Soccer, tried to figure it out.

Ryan O’Hanlon: So, Clint, you’re a professional athlete. However, you’re also someone who uses the word “Aquinian” in emails and someone who is a Pacific Standard-published author! You read a lot, which is a ridiculously simple thing to say, but an important one for our purposes. You especially read a lot of sports writing. How has the writing—and, more generally, the way you look at sports—changed since it’s become the full provider of your livelihood?

Clint Irwin: I’ve become fascinated recently with the statistical movement in sports and the desire to quantify and predict events in sport. My journey started with Soccernomics and Moneyball, which have led me to some of the more cutting-edge people that I follow on Twitter. (I like to think I’m cutting-edge.) If the writing wasn’t simply about what actually happened—in the cold, harsh truth of this results-based life—it started to seem like noise. I almost felt ashamed; I was rejecting prose that was undoubtedly well-crafted and had meaning to someone, but it simply no longer corresponded to the events I witnessed on TV or in person. So much writing had become, in my view, fantasy.

As statistics has come closer to measuring the unseen, it seems that the other realm is becoming ever less interesting. The unseen can now be quantified, rather than merely interpreted.

O’Hanlon: As you say, you’re not rejecting the writing because it’s not good writing, but because, ultimately, it’s meaningless to you. You want to do your job as best as you can, and that’s pretty much all that matters when you’re out on the field. A lot of this thinking you say you reject is concerned with interpreting what you, the fan, are seeing on a field or a court and interpreting it in a way that’s meaningful to you. And for the majority of people who are “part of sports”—again: fans—that’s what really matters. Looking at the game in a strictly quantifiable way maybe lessens the enjoyment for some, and if you’re not enjoying sports, why are you watching? (Jaguars fans, don’t answer that.)

Irwin: I’m watching sports, and I think this is probably the main reason the greater public watch sports, because I want to see the sensational. I want to see the super-human, those feats of strength and speed that make you notice that this is a special human. Diana Nyad swimming across the Straits of Florida. Usain Bolt running fast. LeBron James being LeBron James. It’s more of a classical sense of athletics, the desire to see man do things, just because it’s there to be done, unencumbered by any sort of superfluous interpretation. And I know that this itself smacks of the writing that I’ve previously criticized, but hey, when transcendence smacks you in the face, you normally don’t need any sort of interpretation. That’s why I watch.

O’Hanlon: I think that’s true for most people—aside from all the other weird reasons we watch sports. So, you answered my … rhetorical question and simultaneously disqualified yourself from this debate. (This is not a debate.) I win! (There is nothing to win.) But, anyway. You watch sports for the same reasons, yet you look at sports differently now, tending toward the analytical side. How, though, has that changed the way you watch a game? Or are these things totally divorced for you? You think about sports and play them in one part of your brain, and you freak out about LeBron James in another. Or maybe these things—the knowledge that people want to see some breathtaking shit—are present in, or at least informing, the way you play?

Cheating Week

We’re telling stories about cheating all week long.

Irwin: Why I watch sports has certainly changed since I’ve moved from (regular?) athlete to this-is-how-I-put-food-on-the-table athlete. I used to be totally consumed by what the “narrative” was, what it meant for an athlete’s “legacy.” But since I’ve joined this club of people who make a living by playing games, it’s made the cacophony of everything that happens outside of the actual game seem silly. You would think that maybe these things would matter more to me, since it’s the primary reason why athletes are able to play these games as an occupation. (Buzz = $.) However, it makes me enjoy sports less. The constant water-cooler talk about sports is unbearable for me, no matter what sport it is. As much as people think they understand what goes on behind closed doors, and how the “experts” can explain exactly what’s happening, it’s really nowhere close to reality. (If sports were MTV’s True Life: “You think you know, but you have no idea.”) I don’t hold myself in any higher regard as a viewer. I know nothing about LeBron other than what I see him do on the basketball court.

The inherent desire for the sports-watching public to see something “breathtaking” is almost regarded as a responsibility for athletes. If you’re not capable of the breathtaking as an athlete, you’re probably either a) not very good or b) a boring player. The first option (a) will mean that your pro career will probably be pretty short. The second option (b) means that your career will be fairly long (boring; read: steady, unspectacular).

The responsibility that I speak of, though, is hard to coax. I’d say most players aren’t purposely pulling some ridiculous moments out on purpose. There are exceptions, of course. But for the run-of-the-mill athlete, you’re mostly trying to complete your task and not screw up. The spectacular, a lot of times, is an anomaly for 95 percent of the pro athletes you see. (SO STOP GLORIFYING THEM!!! Unless they’re soccer players, in which case, we need all the help we can get.)

O’Hanlon: You can’t separate those things, though, as you say. Without the breathtaking moments and the narrative that gets built around them, we wouldn’t have the oh-so-popular apparatus that allows human beings to get paid a living wage to be really good at sports. Or maybe we would—but it’d be way different from what we have now, and that’s a discussion for another time.

So, you talk about doing all the little things and getting all the tiny advantages that let you be the best keeper you can be—but you mention the pull of the spectacular. Efficient shutout after efficient shutout is great, but it’s not necessarily getting you a “save of the week” trophy, which equals more visibility. It’s a team sport, obviously, but it’s also your career. Just being really good at what you do is often not enough to reach whatever your ultimate achievement would be in whatever it is you do for a living. Is there, then, an occasional urge to stand out from everyone else in ways beyond your goals-against-average? (A more cynical person might say: like talking to me about abstract sports concepts.) The more people who know you and see you doing something, the better it presumably is for you. Basically, what I’m asking: When are you gonna give in and break out the scorpion kick?

Irwin: Am I trying to stand out by exchanging emails about abstract sports concepts? What, I thought everyone did that? Point taken; You’ve seen through my detached veneer and fingered me as another glory-seeking, attention-driven professional sports person. Just call me the High-Brow Terrell Owens. (Please don’t.)

The scorpion kick might be a bridge too far for my limited athletic talents but it’s a fair point to make, that athletes don’t want to toil through their careers in complete obscurity. I doubt any athletes would say, “I want a long career of mediocrity in which no one notices my failures or successes.” Athletes just aren’t wired that way and neither are most humans. It’s only natural to want to be recognized, whether in sport or life in general. Which is to say that yes, maybe the whole “sport mirrors life” narrative that a lot people ascribe does have some weight. But it’s more in the trivial details of living and working with other people than the triumphant accomplishments of the athlete in the arena.

Did I just change my mind about everything? Probably. Twice. You media types and your trap questions.