If I have one thing to say about Holly Grigg-Spall’s new book, Sweetening the Pill: How We Got Hooked On Hormonal Birth Control, it’s that it brings together ideas in creative ways and comes out with conclusions that are new to me.

The book is an interrogation of the popularity of hormonal birth control in the U.S. In one argument, Grigg-Spall begins with the fact that women’s bodies are a fraught topic. For hundreds of years, the female body has been offered as proof of women’s inferiority to men. Feminists have had two options: (1) embrace biological difference and claim equality based on essential femaleness, or (2) reject difference and claim equality based on sameness.

Largely, Grigg-Spall argues, the latter has won out as the dominant feminist strategy. Accordingly, all things uniquely female become suspect; they are possible traitors to the cause. This includes ovulation, menstruation, and the mild mood swings that tend to accompany them (men have equivalent mood swings, by the way, they’re just daily and seasonal instead of monthly-ish).

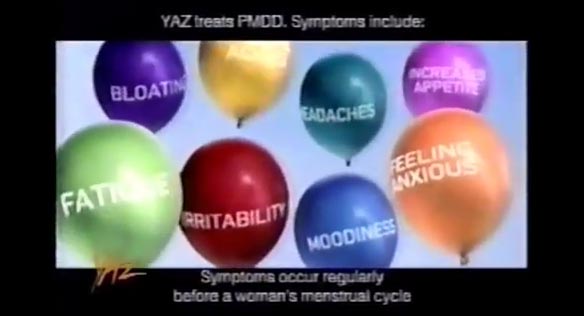

Hormonal birth control, then, can be seen as a way to eliminate some of the things about us that make us distinctly “female.” ”Science is making us better,” the message goes. By getting rid of our supposedly feminine frailties, “we are [supposedly] becoming better humans….” A quick look at birth control pill advertising reveals that this goes far beyond preventing pregnancy. Commercials frequently claim other benefits that conform to socio-cultural expectations for women: reduced PMS, clearer skin, and bigger breasts. This Yaz commercial, for example, claims that the pill also cures acne, irritability, moodiness, anxiety, appetite, headaches, fatigue, and bloating.

To add insult to injury, Grigg-Spall notes, advertising then frames consumption of the pill as liberation. In this commercial for Seasonique, the pharmaceutical company positions itself as women’s answer to a mysterious oppressor. ”Who says?” is repeated a full eight times.

Othershavecriticized Grigg-Spall for, among other things, essentializing femaleness: utilizing that strategy for equality that embraces women’s difference from men and asks others to do so as well.

I’m coming down on the side of “huh!?” The pill made an immeasurable difference for women when it was introduced as the first effective, female-controlled birth control method. There’s no doubt about that. Her book asks us whether our designation of the pill as a holy pillar of women’s equality still applies today. I think it’s worth thinking about.

This post originally appeared onSociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.