Three days after September 11, 2001, Congress voted in favor of using military force against those who “planned, authorized, committed or aided” the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Only one member of Congress, Barbara Lee (D-California), voted against the measure.

That vote was representative of the views of the American public—the country had been attacked and Americans felt a level of threat from abroad that had not been experienced since Pearl Harbor. In the wake of 9/11, Americans generally accepted the increased role of Big Brother in their lives, sacrificing their privacy in the name of security.

We waited in longer security lines and accepted having our bags searched and our bodies scanned. On railways and other mass transit, we accepted random stop and searches. And we lined up to get passports to come in and out of the U.S. when a driver’s license used to do the trick.

For the generation that developed their political identities in the wake of 9/11 it appears that their political attitudes have been shaped more by the privacy they were asked to give up after the attacks than by the attacks themselves.

In 2005, Gallup found that only 30 percent of Americans adults polled thought that the Patriot Act, which allowed the federal government to conduct warrantless surveillance of people suspected of terrorism-related activities but who were not linked to terrorist groups, “went too far.” And in the summer of 2007, as one of us has publishedelsewhere, according to a poll conducted by the University of Connecticut, over 80 percent of the public thought that the government was very or somewhat likely to monitor the activities of “ordinary Americans.” That same poll found, however, that while a majority of Americans opposed the government monitoring ordinary Americans, they were not particularly worried about it.

POLITICAL SCIENTISTS THINK ABOUT generations in terms of when they were socialized into politics. People develop their identities in their late teens and early twenties. The events that occur alongside this development can have reverberations for many generations to come. Instead of thinking about when people were born, political scientists tend to think about major events that happened during the years in which people form their political identity. Individuals who were still developing their views on politics in 1932, for example, were socialized by the Great Depression. They developed a very distinctive liberal leaning and embraced a government role in regulating the economy and providing social welfare that never faded. They continued to hold these views their entire lives.

People who are 18-39 today were between the ages of six and 27 when the towers fell on 9/11, but their views about the security vs. privacy tradeoff challenge traditional wisdom.

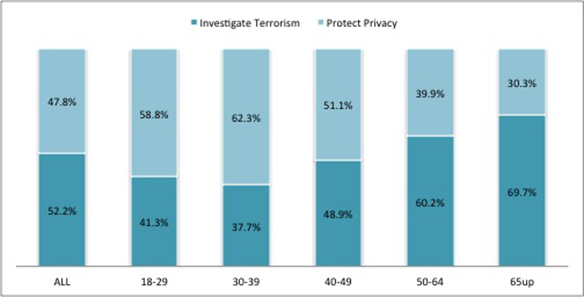

What do you think is more important right now: “The federal government should investigate possible terrorist threats, even if that intrudes on personal privacy,” or “The federal government should not intrude on personal privacy, even if that limits its ability to investigate possible terrorist threats?”

In the 12 years since the terrorist attack, many have noted that 9/11 was the biggest socializing factor in young people’s lives. Observers have noted that this generation expresses a high degree of patriotism and question whether this will spill over into policy attitudes. One possibility is that those in their formative years during 9/11 would respond with an embrace of security measures that, while aiming to curb terrorism, also infringe on privacy. Basically the thought is, if you were socialized during an eminent terrorist threat and constant infringements on your privacy, you would become more willing to trade privacy for security. The thing is, more than a decade after the attacks, we now know that those socialized in the wake of 9/11 instead downplay the threat of terrorism and place a much higher premium on protecting their privacy.

In a recent poll conducted at the Center for Public Opinion at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell, we asked a series of questions about people’s willingness to trade privacy for security or vice versa. Across a series of questions, we find that people under 40 are extremely concerned about privacy issues and willing to sacrifice their safety to keep their lives away from the eyes and ears of government monitors, but that those over 40 are far more likely to trade their privacy for security.

Seventy percent of respondents over the age of 65 and 60 percent of 50- to 64-year-olds say that the government should investigate terrorism threats even if it invades on citizens’ privacy. For those between the ages of 18 and 29, we find the opposite: 59 percent report that “The federal government should not intrude on personal privacy, even if that limits its ability to investigate possible terrorist threats.” Only 41 percent in that group favor investigating terrorism over privacy concerns. That’s a 29 percentage point difference between those 18-29 and those 65 and older.

Those who were in their late teens or early twenties when the towers fell are even more concerned—62 percent of them say that the government should not invade privacy even if it limits investigating terrorism.

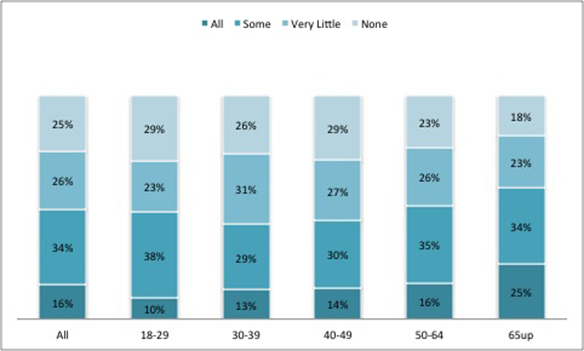

How much of your personal information would you be comfortable sharing with the government if it had the potential to protect the U.S. against a future terrorist attack?

When we examine the full range of data it appears to break at the 40 to 49 age group. In another question, we asked how much personal information survey respondents would be comfortable sharing with the government if it had the potential to protect the U.S. against a future terrorist attack. Again, the vast majority of those under 40 say very little or none, while older adults are much more willing to share their personal information.

And when asked if they were more afraid of an invasion of privacy or a terrorist attack, respondents under the age of 40 were far more likely to answer an invasion of privacy. The opposite was true for those over 40.

The irony, of course, is that the majority of people in this generation appear to be totally comfortable answering intimate questions online and volunteering loads of information to companies like Facebook. But while they may be more willing to publicize their drunken infidelities to their friends and casual acquaintances, the idea that the government can “friend” them without their knowledge seems to scare them far more than the idea that terrorists might plot another attack.

For the generation that developed their political identities in the wake of 9/11 it appears that their political attitudes have been shaped more by the privacy they were asked to give up after the attacks than by the attacks themselves.

Thirty-year-old Edward Snowden is not an outlier; he’s just a public member of his generation.