Efforts to reduce partisanship within American government have usually failed. “Civility initiatives” have gone nowhere, making primaries more open doesn’t seem to produce more moderate officeholders, and California’s top-two reform hasn’t made much of a difference yet (although it’s still early). Nor does non-partisan redistricting tend to produce less partisan legislators. And if efforts to get senators to sit together at State of the Union addresses have moderated the Senate at all, it’s really hard to see it.

These initiatives’ failures, of course, don’t keep politicians, journalists, and reformers from repeatedly touting them. But one thing that may actually make a difference in politicians’ partisan behavior hasn’t received much attention. That would be journalistic coverage of politics.

Ideologically extreme officials are more vulnerable to defeat where there is better coverage. They have greater incentive to behave as moderates if they know voters are watching.

In an article called “A Theory of Parties,” which I wrote with Kathy Bawn, Marty Cohen, David Karol, Hans Noel, and John Zaller, we investigated this topic a bit, drawing on an earlier conference paper written by Cohen, Noel, and Zaller. (The Bawn et al. article is being presented with the Heinz Eulau award at the American Political Science Association conference in Chicago later this week, so expect me to be talking about it a lot.) These papers examine the congruence, or overlap, between media markets and congressional districts. That is, in perfectly congruent media markets and districts, everyone within a media market would be represented by the same member of Congress. In such a highly congruent situation, journalists have a strong incentive to cover that member of Congress’ daily activities, which has the effect of increasing voters’ knowledge of that member. When congruence is low, there is little incentive to cover the behavior of a given representative, since a high percentage of viewers will be represented by someone else.

It turns out that this congruence matters. We tend to think of more ideologically extreme members of Congress as more vulnerable to electoral defeat, and there’s plenty of evidence to support that. However, this vulnerability is mediated by the congruence of districts and media markets. Extremists only get tossed out of office if voters know they’re extreme.

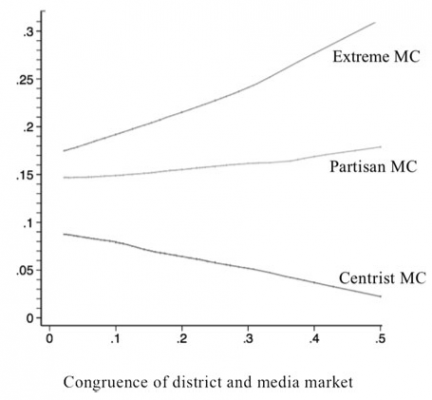

The graph below divides up Democratic members of Congress (MCs) in the Republican wave year of 1994 by their ideological leanings (centrists, partisans, and extremists) and estimates their likelihood of losing reelection that year based on the congruence of their district and media market. What the results show is that relatively extreme members were much more vulnerable where congruence was high. This is because journalistic coverage of them was better; voters knew their MC was extreme because the media reported what they did in office. Relatedly, centrists were safer in such districts. In the districts where there was less congruence (and presumably less coverage of individual members), it didn’t much matter whether the members were voting in extreme or centrist ways—they were about equally likely to retain or lose their seats.

Probability of Defeat for Democratic Members of Congress in 1994

The upshot of this is that ideologically extreme elected officials are more vulnerable to defeat where there is better journalistic coverage. They have greater incentive to behave as moderates if they know that voters are watching.

So if you want more centrist elected officials, there’s your reform: have journalists provide better coverage of politics. That’s far easier said than done, of course. Newspaper readership is in steady decline, as is the number of regular newspaper readers. Coverage of politics, particularly local politics, is becoming more scarce. And there probably aren’t enough billionaires to buy all the struggling media companies in the United States.

Nonetheless, improving media coverage of politics is a worthwhile goal. Even if it doesn’t end up reducing partisanship by much, the worst you end up with is an informed electorate and more employed writers.