Last week the world reacted with surprise when Pope Francis I, returning on a plane from a visit to Brazil, said, in regard to gay priests, that “If they accept the Lord and have good will, who am I to judge them? They shouldn’t be marginalized…. They’re our brothers.”

This was a slightly odd way to put it. The pope, as the leader of the Catholic Church and, as they say, Christ’s Vicar on Earth, is precisely the person to judge. He has the capacity to judge and he decided, in some way, not to judge unfavorably.

None of this has anything to do with church doctrine per se, which does not condemn the inclination to homosexual behavior, but prohibits the behavior itself. This has been its stance for years. (The Church, it’s worth pointing out, also prohibits heterosexual sex between unmarried people.) Nevertheless, the pope’s remarks signal a shift in the Church’s attitude toward gay people—at least as far as his followers are concerned.

Pope Pius XII appeared to have a curiously sympathetic relationship to the regime of Adolph Hitler, and the Church didn’t officially accept Galileo’s heliocentric solar system until 1992.

But this is nothing new. Historically, the Catholic Church has altered its official teachings, following (from quite a distance, sometimes) what we might think of as global public opinion. And it’s supposed to do that.

Some conservative observers reacted with concern. Was this an attempt by the Church to become more “relevant?” Much as many elderly American Catholics find some current practices at Mass irritating (characterizing the new music at many suburban churches as “nuns playing the banjo,” for example), the faithful often find the Church’s new efforts toward inclusion to be both disgraceful and a little pathetic. Consider all of the attention, most of it negative, that the Diocese of Brooklyn garnered this year for its advertising campaign promotingthe Lamb of God as the “original hipster.”

That, of course, is patronizing and just plain silly. Hipsters (and Brooklyn ought to know) value non-mainstream fashion sensibility and urban living, among other things. A carpenter who lived with his peasant parents until embarking on three-year religious quest is not a hipster, no matter how far you stretch the definition.

Those who find the Church’s lurches to the left unwarranted could be taking their cue from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. “Has the Catholic Church ever changed its teaching? No,” saysUnited States Catholic Catechism for Adults, a guide put out by the conference, “for 2,000 years the Church has taught the same things which Jesus taught.”

But that’s misleading. Part of the problem is the way the Bishops characterize the Church’s “teachings.” Some teachings are more important than others. The Church is a living organism, and has always reacted to society’s progress. As Catholic observer and journalist Michael Leachwrites:

Until 1966 every Catholic who ate meat on Friday went to hell. Those who were born after 1966 did not. Catholics before 1966 believed that rule and its penalty would never change. Now they wonder what happened to the poor souls who ate a hamburger before the change.

That’s probably the same thing that happened to those who charged interest on loans before the Church finally stopped worrying about that practice in the 19th century. Leach continues:

The church has not only changed throughout the ages, it has changed more in the 50 years since Vatican II than in the first 2,000 years — just like everything else in the world. Today’s cell phone is tomorrow’s telegraph. Two or three of the teachings of the church are poised to fall like the Berlin Wall, unexpectedly but not as a surprise.

But teachings of the church don’t “fall” merely as a reaction to whatever fads are popular in society at the time. Catholic scholar (and, oddly enough, senior circuit judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit) John T. Noonan, Jr., has a very interesting book on how change works in the Catholic Church. As he writes in A Church That Can and Cannot Change: The Development of Catholic Moral Teaching:

The act that is intrinsically of a particular character is so regardless of circumstances and motive. Judgment of the act can be certain and unchanging. With this intellectual satisfaction the act of lending was once pronounced to be intrinsically gratuitous and marriage was described as intrinsically indissoluble, and John Paul II discovered slavery to be intrinsically evil.

But the Church’s understanding of what something is intrinsically changes, a lot.

John Paul II and [Catholic theologian] John Henry Newman agreed that the intrinsically evil could never be done without sin. But Newman [in 1863] thought that to hold a human being in slavery was not intrinsically evil. For John Paul II [in 1993], slavery was a prime example of what could never be lawfully committed, of what was indeed an instance of intrinsic evil. Their agreement on the nature of the intrinsically evil and their disagreement on slavery generates questions. Is it possible that what is intrinsically evil in one era is not so in another? How then can the intrinsically evil be universal, immutable, always and forever? Or, if the pope was right on slavery, was Newman wrong? Between Newman and John Paul II, there was a change in the theological judgment on slavery. How account for it?

Slavery, religious liberty, usury-on these topics, the teaching of the Catholic Church has changed definitively. On divorce a change is in progress, All change, the cynics say, is glacial. So it must seem to those struggling to foster it. Mutations are small, sometimes sudden. The major mutations that have occurred exhibit what the Church is capable of.

The Church doesn’t change without great deliberation.

Built into this is a structural understanding that there are some Catholic stances that are more clearly developed by the Church than others. While many (particularly non-Catholics) tend to think of the prohibition against gay marriage, the opposition to birth control, and the maintenance of a celibate, male priesthood as Catholic “doctrine,” there’s doctrine and then there’s doctrine.

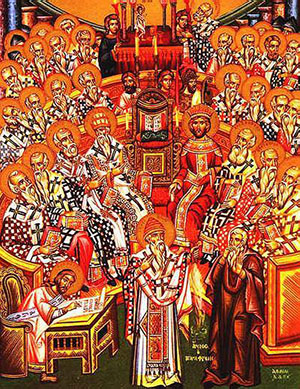

Before 1818, marriages between Catholics and non-Catholics were considered invalid. For another 47 years, the Church taught that all non-Catholics, even Baptists or Presbyterians, would go to Hell, having not accepted the true church. Until the meeting of the First Council of Nicea, in 325, the Church hadn’t even officially decided that Jesus was divine.

Eastern Orthodox icon depicting the First Council of Nicea. (IMAGE: PUBLIC DOMAIN)

There are certainly a number of tactical and even philosophical mistakes the Church has made over time. (Consider: Pope Pius XII appeared to have had a curiously sympathetic relationship to the regime of Adolph Hitler; the Church didn’t officially accept Galileo’s heliocentric solar system until 1992; and the Vatican officially opposed democracy itself through the 19th century.) But the legal and bureaucratic structure of the Church allows it, after lengthy, complicated debate, to incorporate new scientific and cultural information into doctrine.

The most stable, not-available-for-change policies are de fide definita, “(Matter) of the defined faith,” meaning doctrine that is “not open to denial, further speculation, or revision, and which is required to be held as an article of faith by all believers.” This is something like the teaching that Christ is present in the Eucharist or that Mary is the mother of God.

But there are only a handful of teachings that fall into this category that are controversial to the average Christian.. Priestly celibacy, the ban on contraception, and even the abortion prohibition aren’t de fide definite. They are ordinary Church teaching, according to Dennis Doyle, professor of religious studies at the University of Dayton. This doesn’t mean that such teachings aren’t very, very important; it’s just they could potentially be changed in the future.

Some find the changing practices of the Church disconcerting. Is nothing sacred? In the years after Vatican II, the Ecumenical Council that took place between 1962 and 1965, priests started to say Mass in whatever language was spoken in the country (rather than Latin), faced the congregation during services, and placed the Eucharist in the hands of parishioners (rather than their mouths). Many wondered how far all of these changes could go.

Fran Lebowitz (who is not at all Catholic) wrote in 1981 of a fictional, laid-back “Pope Ron,” who has a cute kid, an ex-wife, and has taken the walls of the Sistine Chapel “down to its natural brick.” And how in the future, pretty soon man, we might have a Pope Ellen or a Pope Ira.

The Onion recently characterized the history of Catholic reform as one in which in 761 the Vatican “declares the one-time ‘Year of You,’ in which it encourages the world’s Catholics to just smile, be themselves, and overall have a blast, regardless of whom they love” and in 1349 “mass population loss due to the Black Death forces the Church to temporarily allow gay priests, leper priests, boy priests, and horse priests.”

Both of these examples are satirical, but they represent a common belief that while the Church is strict about its rules, it’s also possible to change the rules when new information becomes available.

So what’s going to happen to those gay men Pope Francis has declined to judge? How is the church going to change in the next few years? It’s hard to predict such things.

The true meaning of Pope Francis’ statement, and how we’re to judge it, remains to be seen. It might mean nothing. But in his first few months in office, the Argentine Pope Francis has already proven himself to be an unusual and vaguely progressive pope. He’s known to be very concerned with the lives of the world’s poor and the economic systems that have put them in that position. Reuters reported that, as of June 24, the pope had “not spent a single night in the opulent and spacious papal apartments,” preferring to sleep in much more humble quarters.

But our current pope, despite his famous use of Twitter, is not operating like a hot-headed professional athlete or a drunken rock musician; he is not given to spouting random off-the-cuff pronouncements to be misinterpreted by the media.

He knew what he was doing. And he knew what the reaction to any sympathetic statements about homosexuality would be. Who know what the future might bring.