A recent RadioLab podcast, titled “The Bitter End,” identified an interesting paradox. When you ask people how they’d like to die, most will say that they want to die quickly, painlessly, and peacefully—preferably in their sleep.

But if you ask them whether they would want various types of interventions were they on the cusp of death and already living a low-quality of life, they typically say “yes,” “yes,” and “can I have some more please.” Blood transfusions, feeding tubes, invasive testing, chemotherapy, dialysis, ventilation, and chest pumping CPR. Most people say “yes.”

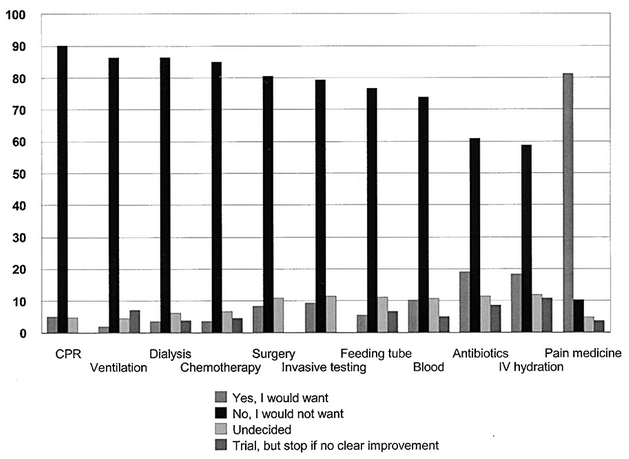

But not physicians. Doctors, it turns out, overwhelmingly say “no.” The graph below shows the answers that physicians give when asked if they would want various interventions at the bitter end. The only intervention that doctors overwhelmingly want is pain medication. In no other case do even 20 percent of the physicians say “yes.”

What explains the difference between physician and non-physician responses to these types of questions? University of Southern California professor and family medicine doctor Ken Murray gives us a couple of clues.

First, few non-physicians actually understand how terrible undergoing these interventions can be. He discusses ventilation. When a patient is put on a breathing machine, he explains, their own breathing rhythm will clash with the forced rhythm of the machine, creating the feeling that they can’t breath. So they will uncontrollably fight the machine. The only way to keep someone on a ventilator is to paralyze them. Literally. They are fully conscious, but cannot move or communicate. This is the kind of torture, Murray suggests, that we wouldn’t impose on a terrorist. But that’s what it means to be put on a ventilator.

A second reason why physicians and non-physicians may offer such different answers has to do with the perceived effectiveness of these interventions. Murray cites a study of medical dramas from the 1990s (E.R., Chicago Hope, etc.) that showed that 75 percent of the time, when CPR was initiated, it worked. It would be reasonable for the TV watching public to think that CPR brought people back from death to healthy lives a majority of the time.

In fact, CPR doesn’t work 75 percent of the time. It works eight percent of the time. That’s the percentage of people who are subjected to CPR and are revived and live at least one month. And those eight percent don’t necessarily go back to healthy lives: three percent have good outcomes, three percent return but are in a near-vegetative state, and the other two percent are somewhere in between. With those kinds of odds, you can see why physicians, who don’t have to rely on medical dramas for their information, might say “no.”

The paradox, then—the fact that people want to be actively saved if they are near or at the moment of death, but also want to die peacefully—seems to be rooted in a pretty profound medical illiteracy. Ignorance is bliss, it seems, at least until the moment of truth. Physicians, not at all ignorant to the fraught nature of intervention, know that a peaceful death is often a willing one.

This post originally appeared onSociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.