For a long time, the Taj Guest House was about the only place you could get a beer in Jalalabad. The provincial capital, about 30 miles from the infamous mountains of Tora Bora, has been the main staging ground for U.S.-led forces in the eastern part of Afghanistan since the early days of the war. When I showed up in the city in November 2011 to report on the propaganda efforts of a franchising Taliban, I found myself at the Taj. There wasn’t much to the pub—just a bamboo-covered bar, a fireplace, a glass-fronted cooler with some Heineken stacked inside, and a few bottles of vodka and other spirits lined up under the red glow of a lamp.

Plus there was an odd little sign: “We share information, communication, (and beer).”

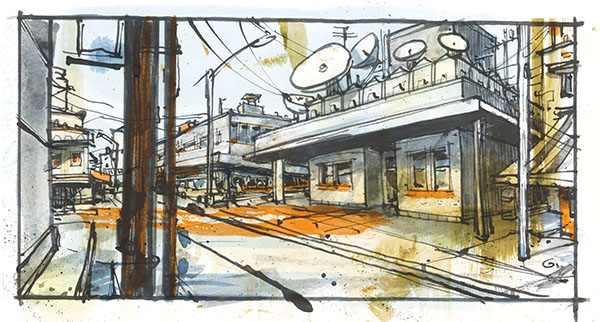

Behind the Taj’s main building was a second villa with an imposing cluster of satellite dishes and antennae jutting from its roof. The villa housed a small team of young expatriates, half a dozen or so women and men who generally kept to themselves. Their apparent leader was a tall, broad-shouldered man who seemed always in a hurry. Looking like a cross between a mountaineer and a mathematician, he had a salt-and-pepper beard and curly hair that hung down to his shoulders, and he favored a uniform of black polo shirts over tied-dyed tees. His name was Dr. Dave Warner.

War zones attract a lot of sketchy characters. In Afghanistan and Iraq, where defense contractors have generally outnumbered soldiers on the ground, the cast of extras has been especially sprawling and inscrutable—security experts, mercenaries, aid workers, engineers, intelligence types, and consultants of every kind. It was just a guess, but given the array on the roof, I took Warner and his team for spooks of some kind.

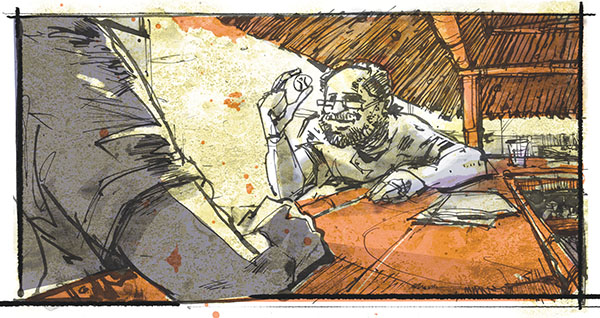

One night, while a fire was burning in the hearth at the Taj, I found Warner sitting at the bar, staring at his laptop through small, square glasses. I grabbed a beer and struck up a conversation, looking over his shoulder as a digital animation twirled across his screen—rings of gold, purple, and blue rotating over a satellite image of the city of Jalalabad. To my surprise, he was happy to explain. “See that?” Warner said, zooming in and pointing at a small doughnut shape spinning around a larger figure. “That’s a fruit vendor going around and around the market.”

What we were looking at was a data-visualization tool he had created, called Antz. The patterns on the screen reflected actual information from the environs in Jalalabad—records of attacks on coalition forces, funding and logistical data for various reconstruction projects, the movements of people. Warner believed the program was a step toward better intelligence analysis. But he made a point of telling me that none of the information on the screen was classified. He had built the model entirely from freely available data that he and his team had harvested from the city.

I was at best half right in my guess about Warner’s occupation. He did indeed work for U.S. intelligence sometimes, he explained, but he wasn’t a spy. On principle, he refused to get a security clearance, out of a belief in something he called “radical inclusion.” The most valuable information in a conflict or disaster zone, he said, was information that could be shared with everybody.

The term radical inclusion stopped me. I recognized it from the summer of 1998, when I had gone to Burning Man, the hedonistic-fire-worshipper-art-festival that occurs every summer in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert. Radical inclusion is one of the event’s “Ten Principles.” When I mentioned this, Warner’s eyes lit up. He dug into his T-shirt and pulled out a shining Burning Man medallion. “Dude,” he said, grinning in the firelight. “This is a Burner bar.”

WARNER’S ENTIRE TEAM—WHICH he called, in all seriousness, the Synergy Strike Force—had just attended Burning Man that summer. He himself had been attending annually since 2002. And the bar, it turned out, was his bar.

Warner held the lease on the Taj, and he ran it with the help of an Afghan man, a former shepherd turned beekeeper turned tobacconist turned pool cleaner turned guesthouse manager named Mehrab. By design, the Taj sat “outside the wire,” beyond the security perimeter of the nearby coalition airfield. It was not only a place to drink and flop but also a kind of grand social experiment—an outpost of the Burning Man ethos in the Afghan desert.

What Warner meant when he called the Taj a “Burner bar” was that it operated, in part, according to a barter system. One of the standing rules at the guesthouse was that any expat could exchange information for booze. In a war zone where so many different agencies, companies, and contractors passed like wary ships in the night, one of the biggest problems was that no one could coordinate knowledge. No one, that is, except maybe a bartender. Under the banner of “Beer for Data,” Warner had turned the Taj into a major clearinghouse for information in Jalalabad. It accumulated by the terabyte on his hard drives: construction plans, hydrology surveys, health-clinic locations, election polling sites, names of farmers, number of trees on their farms, number of acres. What Warner collected he then passed on to the United Nations, the Pentagon, and anyone else who asked for it.

Warner let on that there was a lot more to tell, and that he was making a trip into the field a couple days later. But he offered no invitation, and I went to bed, leaving him at his laptop.

And that was how I met Dr. Dave: a former U.S. Army drill instructor, self-avowed “hippie doctor,” PhD neuroscientist, technotopian idealist, dedicated Burner, dabbler in psychedelics, insatiable meddler, and (weirdest of all) defense contractor. Unlike the guys who had come to the war mainly for the hazard pay, Warner seemed genuinely bent on something far grander—redeeming the debacle of Afghanistan through the gospel of open information.

However romantic that gospel sounded, by this point in the war it was clear there was plenty that needed redeeming. Despite rosy assessments from American politicians and diplomats, Afghanistan was a much less welcoming place in 2011 than it had been on my first visit, five years earlier. In private courtyards, in markets and mosques, and in insurgent enclaves around the country, almost everyone, it seemed, was impatiently waiting for the Americans to leave. The international forces that had been so successful in ousting the Taliban at the outset of the military campaign had been flummoxed by years of grinding insurgency and the persistence of Afghanistan’s complexities—its rules and rites, traditions and customs. Added to all that was a culture of secrecy and mistrust between military units and the development agencies, both international and local, that had rushed into the power gaps left by the Taliban rout.

The war effort, in short, was sophisticated when it came to deploying lethal hardware like drones, but clumsy in just about every other way. A few people in the upper echelons of the command structure were painfully aware of this. Warner knew because he had their ear. He had connections in the Defense Intelligence Agency, the CIA, the Army Special Forces, and the Office of the Secretary of Defense. He also knew what an unlikely figure he cut—a Burner among bureaucrats. When I asked him later why the Department of Defense had turned to him, he shook his head and laughed. “Oh,” he said, “they’re fucking desperate.”

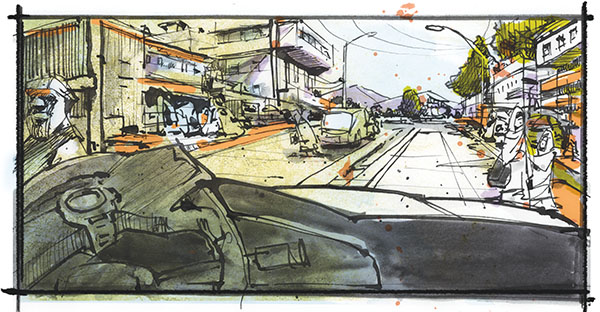

IN THE EARLY MORNING two days later, I heard a knock on my door, followed by Warner’s voice asking me if I could be ready to leave in five minutes. After I had scrambled into my clothes, we piled into a Toyota Corolla and headed out of town, leaving the jammed streets behind and speeding into the empty desert. This was more than a little unnerving. In 2006, I was embedded with U.S. forces for over five weeks, and trips outside the wire were always more or less the same. You’re crammed into a plated Humvee in an armed convoy, bundled up in heavy body armor, twitchy with anticipation. Warner and I had no weapons and no armor, and were at best thinly disguised by the Afghan clothes, scarves, and hats we wore. As we pulled away from the guesthouse, I took a deep breath. Dr. Dave looked at me for a moment and softly said, “Wheeee.”

Warner told me he had been hired—through a contracting company, which was hired in turn by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (better known as DARPA, or the folks who brought you the Internet)—to research ways of crowdsourcing information from Afghans. Because most Afghans lack computers and are at best semiliterate, Warner began with an ingeniously low-tech approach. The Synergy Strike Force enlisted a local radio station to broadcast questions to its audience and ask them to respond via text message—questions like Who’s your favorite cricket player? The team also solicited texts that might deliver more valuable information on, say, agricultural markets—What’s the price of mutton, gasoline, or milk today?

But Warner didn’t stop there. One of the destinations on our trip was a village about 30 miles outside Jalalabad. There Warner led me inside a compound, up a flight of stairs, and into a cramped room with bare concrete walls, where a group of boys were hunched over a bank of dusty Dell computers. They were drawing Afghan flags with Microsoft Paint. On the roof, two banks of solar panels powered the computers, supplemented by a gas-powered generator for rare cloudy days.

Using various pots of money, Warner had built dozens of these solar-powered computer labs around the province. Some, like this one, didn’t have an Internet connection—at least not yet—and were, in Warner’s mind, just stepping stones to the computer literacy that would one day make these kids potential sources of crowdsourced information. Other computer labs, closer to town, had Internet pumped in from the antennae and satellite dishes on the roof of the Taj. In those labs, Warner and his team were teaching Afghans how to use OpenStreetMap, a Web-based platform that allows users to add fine-grained local information to existing satellite maps. (As a result, the OpenStreetMap page for Jalalabad is exquisite.)

Warner was doing it on the cheap—no security details, no armored vehicles—stretching his DARPA funding and his own bank account fairly far. “For the price of two expat security contractors,” he boasted, “I can put Internet to 50,000 students.” But it wasn’t just about power or the Web. Warner sees technology on a continuum that stretches all the way down to the most basic tools. After crossing a rocky, dry streambed, the Corolla came to a halt in a desolate stretch of desert that Warner called “the moon.” A few hundred yards away, in the middle of a sunbaked boulder field, clusters of kids sat on the ground, chanting the alphabet in front of blackboards that Warner had purchased for them. Younger children sat in circles, leaning over notepads: a classroom in the sun. A few tents had been erected nearby: shade for when the heat became unbearable.

As the children chimed out their letters, a few local elders came over to Warner (they knew him simply as an “American businessman” interested in helping them) and showed him a well they had recently dug with his support. Then they guided us to a mat laid out on the ground. Over tall glasses of water and plates of bananas and shiny red apples, Warner and a young Afghan member of the Synergy Strike Force sat with the men as they explained what more they might need—a schoolhouse with walls, an animal clinic, electricity, bridges, irrigation ditches, a cow so they wouldn’t have to buy milk every day, more security, less war.

Warner saw this school as the beginning of a “cyber node,” a place that could eventually be wired up, along with other primitive schools he was scouting on the Pakistan border. To him it seemed obvious—information about the world would bring Afghans out of isolation.

Dave’s work also had the effect, it so happened, of winning hearts and minds in a battle zone. This patch of desert was routinely crossed by insurgents who slipped out of the mountains of Pakistan to make mischief in the remote villages of Nangarhar Province. “If I were a tactical battle-space commander,” Warner said, “this would be called preparation of the battle space.”

I was just beginning to get used to his way of talking, which alternated between turgid military jargon and gonzo flights of fancy. (“I’m dismantling the Death Star,” he told me later, “to build solar ovens for the Ewoks.”) Ultimately, what he wanted to do was help the Department of Defense and all its scattered parts—a hulking war apparatus he derisively called “The Machine”—help itself. “I’ve foolishly created my own counterinsurgency,” he said.

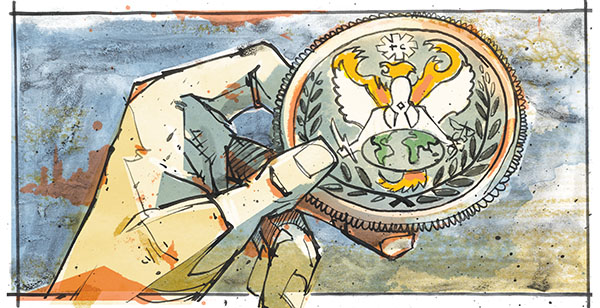

I SPENT THE NEXT few days back at the Taj getting to know the Synergy Strike Force—essentially a loose-knit collective of volunteers and contractors who followed Dr. Dave. The name may have been whimsical, but it wasn’t a joke. Warner showed me a military-style patch he’d designed himself, displaying a white- winged, faceless angel holding a caduceus in one hand, a lightning bolt in the other, and the Earth cradled between the two.

Three members of the group were living at the Taj full-time: Jennifer Gold, 26, a National Guard intelligence analyst who had decided to stay in Afghanistan after her deployment ended; Rachel Robb, 27, a human-rights advocate with experience mainly in South America; and her husband, Juan Rodriguez, 28, a photographer from Colombia. Others made occasional visits, including a pink-haired futurist from San Francisco.

As far as I could tell, being part of the group basically entailed living at the Taj, finding problems, and fixing them. “This is the whole idea behind the Synergy Strike Force—don’t come here with a project that you’re going to try to impose on people,” Robb told me one afternoon in the Taj’s grassy courtyard. “Come here, spend time with people and see what’s needed, and see if you can use your skills.”

In 2009, the group had helped set up a system to crowdsource reports of election-rules violations via text messages from all over the country. And during my visit, Gold, Robb, and Rodriguez were wrapping up a project in which they used SMS texts to reach midwives in far-flung Kunar province to solicit medical information about mothers and their newborns.

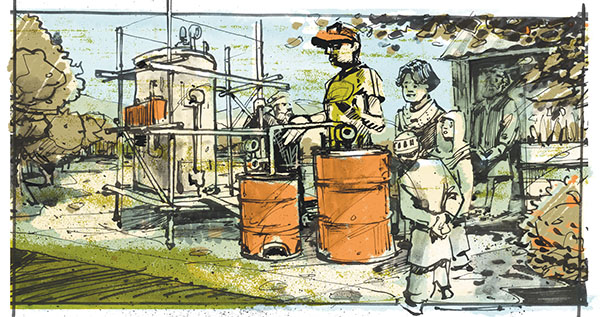

The group was also engaged in various maker-ish side projects worthy of Burning Man. Gold was busy building a methane generator from PVC pipe and an old oil drum. The design, popular among self-sufficiency buffs on the Internet, allows you to filter the gasses that come off human waste into pure methane, which can be used as a fuel source.

No matter what they did, Warner encouraged the group to rely on the local connections he had built up over the years, and to keep their distance from the “battle rattle” of the military—the spectacle of nervous, heavily armed soldiers trying to interface with an equally nervous, unarmed population. “We’re able to approach people because we aren’t carrying all this armor and weapons,” Robb said.

Gold, who had come away disillusioned after serving a tour in Iraq, knew all too well how little could be accomplished from a fortified position behind the wire. “You can’t commute to the war,” she said as we sat in the courtyard, taking a break from her methane generator. “But that’s exactly what these guys are doing.”

NOT SURPRISINGLY DR. DAVE’S own road to war was strange and circuitous. A teenage runaway from a Seventh-day Adventist family in Central California, Warner enlisted in the army in 1980, at age 19. He served as a TOW-missile gunner and drill sergeant before finding his way to college and then medical school. Somewhere along the way he started experimenting with LSD and steeping himself in the tech world. He was particularly interested in finding ways to use virtual reality—then much discussed in military circles as a way to train soldiers—for non-military ends.

In 1994, while Warner was still completing medical school at Loma Linda University, he started working with a seven-year-old patient named Ashley Hughes. Hughes had been paralyzed since birth, but she had motor function in her face—she could wiggle her cheeks, wink an eye, raise an eyebrow. With Warner’s help, she learned to play computer games and drive a remote-control vehicle using only her facial movements, with sensors translating her muscle twitches into digital commands. Later, by outfitting a mannequin’s head with small cameras for eyes and microphones for ears, and then connecting those inputs to a pair of 3-D goggles and a set of earphones, Warner gave Hughes—who had never swum in a swimming pool, climbed a tree, or looked over her backyard fence—the virtual experience of doing all those things.

Warner’s work with Hughes and other patients landed him on World News Tonight With Peter Jennings, and in the pages of The New York Times. It also caught the attention of a few people at DARPA, who approached Warner about doing some work for them. He took the research he’d done on sensors and started designing gloves that could control robots, unmanned aerial vehicles, and other machines.

Bit by bit, however, Warner was becoming less interested in virtual reality or physiology per se, and more interested in the underlying information itself—whether it was the signals being transmitted from the cheek muscles of a little girl with a disability, or spatial models of vendors moving around an Afghan market. “I have a philosophy that I can alter outcomes with information,” Warner told me. “I started this idea in med school. I was like, God, if I could use information to change people’s behavior—to make them better doctors, make patients smarter, that sort of thing—we can reduce disease and suffering.”

He called this philosophy “interventional informatics.”

And he wasn’t the only person contemplating the new powers of information. He began forging friendships with like-minded folks inside the defense, intelligence, and emergency-response communities—all of them looking for ways to use nascent information technologies to help them do their jobs amid natural disasters, terrorist attacks, or wars. Warner was invited along to visit U.N. outposts in Africa, disaster exercises in the U.S., and in, 2004, the tsunami-struck coast of Indonesia. In each, he found that poor cooperation and communication were epidemic among the major players.

Around 2000, he started talking with a man named Linton Wells, an information specialist then in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. By 2006, Wells was trying to figure out how to stimulate more interaction between military and civilian entities in Afghanistan. This had become a huge problem there, as it had in Iraq—both were war zones where international forces and aid agencies mixed in unprecedentedly complex ways. One problem was that people under different charters or chains of command weren’t sharing even unclassified information. So Wells asked Warner to go to Afghanistan and see whether he could come up with some ideas.

That’s when Warner found his way to Jalalabad and to the Taj, which at the time was run by the U.N. Mission. Thursday nights, the end of the Afghan workweek and the eve of the Muslim Sabbath, were particularly popular with the clientele. On one such evening at the Taj, over drinks with the myriad characters at the bar, Warner learned more about the war than he had at any of the official meetings he’d been to that week. A year later, he brought a computer and a hard drive to the bar and posted a sign saying he’d buy a beer for anyone who brought in information. And thus “Beer for Data” was born. He took over the Taj and its bar in May 2009.

It was just the kind of thing his patrons in the military wanted to see. Warner knows how to get things done, Wells told me, how to “genuinely move the ball down the field in ways that a lot of people can’t.”

Eric Rasmussen, one of Warner’s early sponsors at DARPA, has come away similarly awed by the doctor’s capacities. “I was taught by multiple Nobel Prize winners, and Dave is the equal of any of them in intelligence,” Rasmussen told me. Warner has been “trendsetting for a number of very forward-thinking organizations, like the Strategic Studies Group for the Chief of Naval Operations, like DARPA, like the Office of Naval Research,” among others. “He has shaped curriculum for the Marine Corps. He has influenced curriculum for National Defense University. He is a remarkable intellectual force who has managed to hold on to his idealism through everything.” What’s more, he has done it all without a security clearance. “And that,” Rasmussen said, “if you remember the kind of work that he does—and for whom—is astonishing.”

OF COURSE, DAVE WARNER is not the first dreamer the military has ever turned to for help. Back in 2011, when I first met Warner and the Synergy Strike Force, I was immediately reminded of the book The Men Who Stare at Goats, by Jon Ronson, and its descriptions of the First Earth Battalion. In the 1970s, the Pentagon decided it needed a new bag of tools to fight future wars. It also needed to recover from its defeat in Vietnam. Morale in the military was dreadful, and the war machine seemed broken. To make matters worse, intelligence reports suggested that the People’s Republic of China had figured out a way to endow a few thousand children with powers of clairvoyance, psychokinesis, telepathy, and X-ray vision. And so, in 1977, a Pentagon working group on human potential handed a young lieutenant colonel named Jim Channon an assignment: Search the New Age enclaves that were then sprouting in California for possible military applications, and find the outer limits of human potential.

Channon drew up a field manual, published by the Army in 1979, for something he called the First Earth Battalion. The manual included diagrams of chakras and the power of dreams. “The more dreams you have, the more you can create for yourself the future you desire,” the manual advises. Channon wanted to build a kind of super soldier, a warrior monk who could unlock psychic powers and overwhelm an enemy with little more than a kind gaze. Love and synergy, it so happens, were the core purported strengths of such a soldier.

“Synergy is possible when every soldier brings his or her individual best to the group task,” Channon wrote. “It is multiplied in strength again if that soldier truly loves the other members of the unit. Then we shall have the maximum combat power available.”

Channon saw the military as a place where a soldier could become a “guerrilla guru.” His First Earth soldiers would employ “battle tuning” through a daily yoga cat stretch, followed by a primal scream and leap. Their performance-enhancing regimen would include ginseng, amphetamines, rock and roll, and prayers to Mother Earth. “Ethical combat” and “benevolent weapons”—to include “indigenous music and words of peace,” symbolic flowers, and animals—would take on a changing world of conflict. “If in fact we want to have a heaven on earth, then a class of angels should come forth and begin the work,” Channon wrote. “Open your heart. The Universe will feed you.”

There were no amphetamines or primal screams at the Taj—none that I witnessed, at least—but the military’s dalliance with the Synergy Strike Force came from a similar spirit, the end-of-the-road experimentation that goes on when nothing seems to be going right. Sooner or later, the most esoteric, farthest-out ideas of an era are going to get thrown at the most intractable, most-monumental bureaucratic mistakes. Where Channon’s First Earth Battalion had dredged the New Age zeitgeist for military insights, the Synergy Strike Force was drawing from today’s answer to the human-potential movement—the technology-soaked, DIY-happy, crowdsource-everything ethos of Burning Man and the more exuberant corners of Silicon Valley. If you look closely at the angel on the Synergy Strike Force patch, you can see around its neck the same symbol that Warner was wearing the night I met him.

FOUR MONTHS AFTER I left Afghanistan, I stayed in fairly close touch with Warner and the Synergy Strike Force, keeping tabs on their projects and, in my heart of hearts, rooting for them. For a while I even considered volunteering at the Taj—to do what, I wasn’t sure. But the optimism was infectious.

It was not, however, enough to turn the tide in Afghanistan. In February 2012, a few months after I left Jalalabad, U.S. soldiers at Bagram Air Base collected a bunch of library books that Taliban prisoners had been using to pass messages to one another. As part of the disposal process, the soldiers burned them. The trouble was that some of the books were Korans. When Afghan forces on the base reported the desecration, riots erupted across the country. In Kabul, two U.S. officers were killed inside the Ministry of Interior. Seven more American soldiers were wounded in a grenade attack.

The very problems the Synergy Strike Force sought to counteract—the disconnect between the Machine and the Afghans, the chronic distrust—had reached a tipping point. The violence grew so bad that Robb, Rodriguez, and Gold fled the country. The Taj was left in the able hands of Mehrab, the guesthouse’s Afghan manager. Looking for a place to hunker down, the three expats decamped to Reno, of all places, to stay with a friend of Warner’s and continue their work remotely. I was living in Southern California at the time, so I drove up to see them. They were busy designing a project that would deliver neonatal advice to women in the Afghan countryside via robocalls. With characteristic whimsy, they called the project “What to Expect When You’re Expecting in the Hindu Kush.”

Rachel Robb tried to put a good face on their retreat from Jalalabad. “We decided we would be a lot more productive here in the U.S.,” she told me. “We’re definitely going back to Afghanistan. We haven’t left for good. It’s just, we’re here to kind of let things settle down.”

BUT THINGS DIDN’T SETTLE down. Not even close. On August 11, 2012, two gunmen on motorcycles shot and killed Mehrab as he sat in his car. The apparent assassination shook the team; nobody knew whether Mehrab had been killed for his work with the Synergy Strike Force (connecting women to the Internet was not a popular idea with everyone in the province) or whether some local grievance had been to blame.

Around the same time, the defense establishment’s enthusiasm for Warner vanished along with its funding. In September of last year, Warner wrote via email that he was “not getting love from the Machine” for a plan to build something he called the “Cyber Pass”—an extension of his solar-powered Internet schemes focused on areas along the Pakistan border. He was keeping the Taj afloat with his retirement savings and somehow managing to keep wiring a few more schools. He was still making occasional trips to Jalalabad. But the Synergy Strike Force had dissipated, its members moving on to other projects.

Last summer at Burning Man, members of the team gathered once again, and Warner invited me to join them. So I headed out to the Black Rock Desert and pitched a small tent next to Warner’s giant RV. He came out of nowhere, from the dust and the wind, as I was struggling with some rigging for a tarp. He was drinking a beer, wearing a tied-dyed shirt and cutoff jean shorts, with a tie-dyed bandana on his head and another around his neck. “We’re going to the temple,” he said, “for a service.”

The temple is a structure that gets built every year at Burning Man. Burners go there to mourn for whomever they have lost; we were going to mourn for Mehrab. I followed Warner out onto the desert playa, where in the distance the giant wooden statue of “The Man” waited to be burned at the end of the festival. We walked past a 20-foot-tall wooden statue of the word ego inset with trophies, past a field of plastic sunflowers, past men and women in various states of undress and inebriation. Warner took huge strides.

On the far side of the wide, flat, dusty playa stood the temple, a large structure reminiscent of an Asian pagoda, made of thin, filigreed wood panels. On the walls, people had scribbled notes both personal and universal—“I Miss You,” “Humanity Will Prevail”—and incense wafted through the interior. Warner gathered with other members of the Synergy Strike Force. He nailed a pakul hat to the wall, hung an Afghan scarf around it, and added a Synergy Strike Force patch. Around us, Burners wept and prayed. And at the end of the festival, the temple was burned to the ground, with everything in it.