The Supreme Court will shortly decide two cases that deal with the standing of same-sex marriage under the United States Constitution. The first,United States v. Windsor, considers whether a provision of the Defense of Marriage Act (1996) defining marriage in federal law as “a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife” violates the Fifth Amendment equal protection rights of same-sex couples who are legally married under state law. The second, Hollingsworth v. Perry, considers whether California’s voters violated the Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process and equal protection of same-sex couples who wished to marry when they adopted Proposition 8, a ballot initiative which ended same-sex marriage in California by amending the state’s constitution to define marriage as the union of “a man and a woman.”

This pair of cases provides the Supreme Court with a range of potential outcomes. At one extreme, the Supreme Court might act decisively in favor of the status quo, affirming both the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) and Proposition 8 and holding that the federal government and the states may legitimately restrict marriage to opposite-sex couples. At the other extreme, the Court may invalidate both DOMA and Proposition 8 by concluding that same-sex couples have a fundamental right to marry that is protected by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Alternatively, the Court might pursue a variety of middling courses—perhaps invalidating DOMA while either invalidating Proposition 8 on narrow grounds that apply to California alone, or dismissing the case on procedural grounds without addressing its constitutional questions.

Though much of the public may sharply disagree with a decision of the Supreme Court, the decisions of the Court tend to lead public opinion over the long run.

In some respects, the moment seems ripe for the Court to make a bold move in favor of homosexuals’ constitutional rights—as well as their material and symbolic well-being. Polls conducted by nearly every major survey research organization in the country now show majority support for legally recognizing same-sex marriage. Equally as important, survey data shows rapid growth in support for same-sex marriage in recent years. For example, a Gallup poll conducted last month found that 53 percent of Americans agreed that same-sex marriages “should be … recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriages” (including 70 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds). Only 45 percent said that same-sex marriage “should not” be valid.

When Gallup first polled the public about gay marriage in 1996, only 27 percent of Americans favored legal same-sex unions. In less than two decades, support for same-sex marriage rights has effectively doubled, and strong support for marriage equality among younger Americans suggests that the trend toward support for same-sex marriage will continue. A decision in favor of marriage equality would therefore probably begin with majority support that is likely to grow over the coming years.

Still, some supporters of marriage equality worry that the trend in public support toward same-sex marriage may be undermined by a pair of strongly worded pro-equality decisions. In particular, they worry such decisions might produce a backlash against gay marriage that would reverse the trend in public opinion toward support for gay rights and provoke changes in public policy that work against marriage equality. This fear has found a public voice on the Supreme Court in Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, who has publicly claimed that other prominent decisions of the Court on social issues—most notably Roe v. Wade (1973)—”moved too far, too fast,” creating political tides that worked against the Court’s purposes. The New York Times’ Adam Liptak reports some speculation that this line of thinking may lead justices who support marriage equality to avoid the issue in the present cases and wait until some later date to address the constitutional status of same-sex marriage rights.

However, practical political concerns about the prospects of a backlash in support of gay rights following Supreme Court decisions advancing marriage equality are misplaced. Indeed, research in political science provides strong reasons to suspect that the Supreme Court may, in fact, lead public opinion over the long-run. This general pattern is evident in the public’s responses to the Supreme Court’s landmark case addressing homosexuals’ sexual rights, Lawrence v. Texas (2003). Together, both the general pattern of public responses to Supreme Court decisions and the dynamics of responses to the Court’s prior gay rights cases argue that fears that the Court might undermine support for gay rights by robustly embracing marriage equality have the issue backwards. If a majority of the Supreme Court’s justices lead on same-sex marriage, Americans are likely to follow.

JUSTICE GINSBERG’S UNEASE ABOUT the Court outpacing public opinion on social issues reflects a classic worry about American judicial power. Writing in Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville noted the Court’s dependence on the goodwill of its constituents:

[The] power [of the Supreme Court] is immense, but it is power springing from opinion. They are all-powerful, so long as the people consent to obey the law; they can do nothing when they scorn it. Now, of all powers, that of opinion is hardest to use, for it is impossible to say exactly where its limits come. Often it is as dangerous to lag behind as to outstrip it.

The federal judges … must know how to understand the spirit of the age, to confront those obstacles that can be overcome, and to steer out of the current when the tide threatens to carry them away….

Though the Constitution provides the Supreme Court and its justices with substantial buffers against the whims of popular sentiment, the Court ultimately depends on public opinion to preserve its institutionalintegrity and to ensure compliance with its decisions.

Echoes of this sentiment are evident in Supreme Court decisions since the 19th century. In United States v. Lee (1882), Justice Miller wrote, “[the Supreme Court’s] power and influence rest solely upon the public sense of … confidence reposed in the soundness of [its] decisions and the purity of [its] motives.” Likewise, Justice Frankfurter emphasized, “The Court’s authority—possessed of neither the purse nor the sword—ultimately rests on sustained public confidence in its moral sanction” (Baker v. Carr 1962). Justice O’Connor also shared the idea that “The Court’s power lies … in its legitimacy, a product of substance and perception that shows itself in the people’s acceptance of the Judiciary as fit to determine what the Nation’s law means” (Planned Parenthood v. Casey 1992).

Together, these statements suggest the logic of Justice Ginsberg’s comments. When the Court “outstrips” public opinion by making decisions contrary to the “spirit of the age,” it invites said opinion to turn against the Court and its decisions—and their policy implications. But this view of the Supreme Court’s relationship with public opinion is substantially wrong and almost precisely backwards both as a general matter and in regard to the Court’s prior gay rights cases.

AN ARRAY OF RESEARCH in political science—due substantially to James Gibson of Washington University, Gregory Caldeira of Ohio State University, and their collaborators—showsthattheSupremeCourt’slegitimacyisnot dependent on agreement on individual questions of policy between the Court and the public. Instead, judicial legitimacy rests on the public’s perception that the Court uses fair procedures to make principled decisions—as compared to the strategic behavior of elected legislators. These perceptions are supported by a variety of powerful symbols representing the close association between the Supreme Court and the law and its impartiality, such as black robes, the image of blind justice, and the practice of calling the members “justices.”

The public’s response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore, which resolved the contested presidential election in 2000, is perhaps the classic example of the nature and influence of the Court’s legitimacy. Despite the bitter partisan conflict that precipitated the case, the enormous political implications of the decision, the blatant partisan divisions on the Court, and the harsh tone of the dissenting justices, the best evidence available indicates that the public’s loyalty to the Supreme Court did not diminish as a result of the case. In particular, neither Democrats nor African-Americans significantly turned against the Court after the decision.

Judicial legitimacy is not merely a curiosity. It has powerful effects on American politics; Americans’ deep loyalty to the Supreme Court helps insulate it from efforts by those in the elected branches of government to curb or control judicial independence. Additionally—and more importantly here—the Supreme Court’s robust legitimacy in the public mind has important consequences for how the Court’s decisions interact with the public’s policy attitudes.

When the Supreme Court speaks on an issue, the weight of its “moral sanction” rests on a particular side of the relevant policy debate. Its decision enters public debate and—as the political scientist Ralph Lerner theorized nearly half a century ago—allows the “modes of thought lying behind [its] legal language” to “transfer to the minds of the citizens.” As a result, the Court unbalances public debate and, over the long run, pulls public opinion toward its policy positions.

Though much of the public may sharply disagree with a decision of the Supreme Court—producing an initial backlash against the policy implications of a particular ruling or set of rulings—the decisions of the Court tend to lead public opinion over the long run. In a recent analysis of more than 50 years of data on Americans’ collective responses to Supreme Court decisions, I find that public responses to important Supreme Court decisions were typically marked by a negative response in public opinion in the short-term that decays and is replaced by a long-run movement in public opinion toward the positions adopted by the Court.

In other words, on average, there is a backlash in public opinion against important decisions of the Supreme Court. However, these negative responses are relatively short lived. Over the long run, backlash against the Court’s decisions tends to be replaced by significant movement toward positions taken by the Supreme Court.

The public’s reaction to Miranda v. Arizona (1966), the landmark Supreme Court decision which held that police must inform criminal suspects of their constitutional rights to remain silent and to have a lawyer present during any questioning, is indicative of this pattern. The public’s initial reaction to Miranda was strongly negative. Shortly after the decision was handed down in 1966, a poll conducted by the Opinion Research Corporation asked Americans about their views regarding “the Supreme Court’s decision in the Miranda case.” A majority of Americans (56 percent) agreed that “police should again be allowed to be tougher with suspects than they can be now” while only 32 percent agreed that “the present restrictions on the police—since the Court’s decision—are correct and fair.” New York University law professor Barry Friedman writes, “Between 1965 and 1968, polls showed a jump from 48 percent to 63 percent of Americans who thought the courts were too lenient with criminal defendants.”

And yet, in the years since Miranda was handed down, an overwhelming majority of Americans have come to embrace the decision. A survey conducted in 2000 by Princeton Survey Research Associates and Newsweek found that 85 percent of Americans agreed with the “recent decision upholding ‘Miranda Rules’ [Dickerson v. United States(2000)] requiring police to inform arrested suspects of their rights to remain silent and to have a lawyer present during any questioning.” University of Texas law professor Justin Driver summarizes the clear implication: “There can be little doubt, then, that the Supreme Court in this instance expanded the public’s conception of criminal defendants’ rights.”

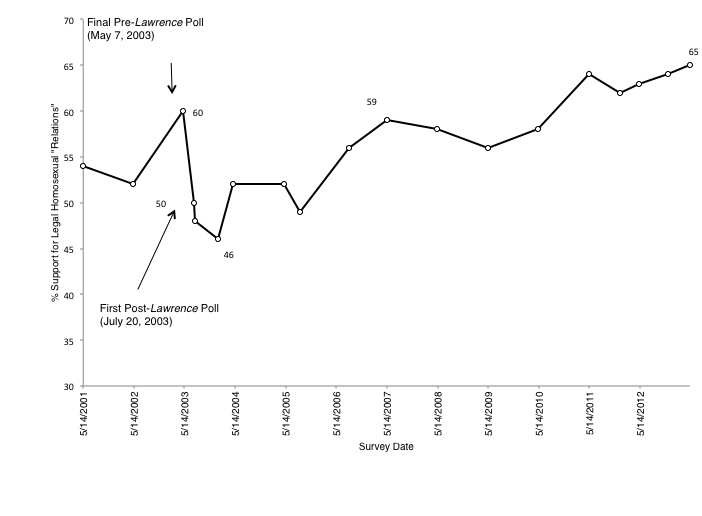

SIMILAR PATTERNS ARE EVIDENT surrounding the Supreme Court’s most important decision expanding gay rights—Lawrence v. Texas, which, in 2003, invalidated state laws which prohibited same-sex sexual activities. Since 1977, Gallup has occasionally asked Americans, “Do you think gay or lesbian relations between consenting adults should or should not be legal?” (In 2008, Gallup replaced the term “homosexuals” with “gay and lesbian.”) It has posed this question at least annually since 2001. In addition to these annual assessments of public support for legal homosexual relations, Gallup also included it in several surveys throughout the second half of 2003 and into 2004.

The sporadic implementation of this question makes it very difficult to get a true sense of the dynamics of public support for this element of gay rights prior to 2001. But the more regular use of this question in Gallup surveys since then provides a reasonably clear picture of the recent history of Americans’ attitudes toward legal same-sex sex as well as a window into the public’s response to Lawrence v. Texas. The graph below shows the percentage of Gallup poll respondents, from May 2001 through May 2013, saying that homosexual (or gay and lesbian) relations should be legal.

Americans’ changing responses to Gallup’s “homosexual relations” question show the backlash and legitimation pattern. Public support for legal homosexual relations had bounced through the mid-50s in 2001 and 2002, peaking at 60 percent immediately before Lawrence in May 2003. Within three weeks, Gallup found that support for legal same-sex sex had dropped 10 percent. A few months later, in January 2004, support bottomed out at 46 percent, before beginning a reasonably steady climb. By May 2007, support had effectively rebounded to its pre-Lawrence level. Since then, support for legal homosexual relations has generally grown, reaching an all-time high of 65 percent in May 2013.

Public opinion about the issue of legal homosexual relations is complicated. It is colored by the changing context of larger debates over gay rights, the cultural context of homosexually, generational replacement, demographic change, and a variety of political events. Attributing all variance in Gallup’s assessment of Americans’ changing attitudes on this issue to a single Supreme Court case is, at best, an oversimplification.

Nevertheless, the survey data help shed some light on the validity of fears that the Supreme Court may permanently damage the cause of gay rights by over-reaching in the pending marriage equality cases. At a minimum, the Gallup data show that the Court’s decision to invalidate state sodomy laws in Lawrence did no lasting damage to the public’s support for gay rights. Changes in public opinion after Lawrence may also indicate that the Supreme Court’s action has helped support a long-run trend in public opinion toward greater support for gay rights.

LOOKING AHEAD TO DECISIONS in Windsor and Perry, Justice Ginsberg’s fears of undermining social change by moving “too far, too fast” seem out of place. A pair of majority opinions strongly in favor of marriage equality may well prompt a temporary backlash in public opinion, but it is unlikely that such a backlash would be permanent. It is also unlikely that any resulting backlash against the policy implications of the decisions would injure the legitimacy of the Court or enable a successful effort to reverse the Court’s decisions via constitutional amendment. Both the Supreme Court and its decisions for marriage equality would successfully weather any storm stirred by the marriage cases.

More importantly, though, pro-equality decisions would not merely survive. Instead, the evidence suggests that they would thrive in the long run. By offering its authoritative voice to validate the constitutional claims of homosexual couples seeking legal recognition of their unions, the Supreme Court may alter the terms of public debate and gradually lead public opinion toward greater acceptance of same-sex marriage.