Bill Rodgers is an American running folk hero. An icon during the running boom of the ‘70s, Rodgers won the Boston and New York Marathons four times each between 1975 and 1980. He hasn’t run Boston since 1996 but is still heavily involved in the running community, making appearances every April as runners prepare for the 26.2-mile journey from Hopkinton to Boston’s Back Bay.

Patriots’ Day is Boston’s holiday and the marathon, the oldest annual marathon in the world, is sacred to Rodgers and the rest of New England. So it was with a heavy heart that Rodgers spoke with us on Wednesday while he was driving home from Massachusetts General Hospital, where he’d just given a medal to a woman who had been hurt in the bomb blast that went off near the finish line of last Monday’s race. Rodgers talked about running’s global reach, what the bombings mean for the future of the marathon, race-day security, and getting the band back together for Boston in 2014.

Marathons are big, sprawling events lined with crowds of people. It’s not a sport contained to a 400-meter track or the walls of an arena. As a runner, how do you psychologically prepare for the landscape?

I always consider running more than a sport. It’s not just a sport, it’s not just a time, it’s not your score versus another team’s score. It’s good for our health. It’s good for our minds. We are meant to move, and you really find that out when you become a runner. It’s a lifetime activity. It has a powerful impact on us—on how we feel, how we change ourselves physically and mentally. And then to go to a race and have people cheer for you, and run with your friends and family? We’re explorers. We see the country and then we go out and see the world. I really feel that running is a celebration of life.

You’re living the life to the ultimate when you’re a runner. We’re so lucky to be runners. That’s what I always tell my friends—we’re so lucky. We get this energy from running, and everyone can have it. All you have to do is go to your local store and buy shoes that fit you well, get some gear, find a park in your neighborhood, and then life is good.

What sort of effect do you think that the Boston Marathon bombings will have on the international marathon community?

Running and marathoning is going to stay strong. I think there will be more security in the days ahead, of course. When you take a look at this sport, there were 45 countries represented. So the attack on the Boston Marathon wasn’t just an attack against America or the marathon, it was an attack against the 45 nations. I don’t think it will happen again. I hope not. But there are people in the world—there’s not too many of them, that’s the good thing—that would do something like this.

Not to sound bleak, but marathons in their nature are vulnerable to attacks—they’re highly visible events with large crowds that are easily accessible. Do you think the bombings will discourage people from running marathons?

They’re vulnerable because of the huge numbers of people that are spectators at big city marathons around the world, whether it’s Beijing or Berlin or Tokyo. But I think generally speaking these are events of goodwill. I think even the terrorists have to recognize that. That this is the wrong thing to do.

I don’t think marathoning globally is going to stop. It will not stop at all. We’re learning more about the science of exercise and what it means to be healthy. We now have data—scientific data, medical data—showing that runners and similar athletes are doing pretty darn good in terms of their long-term health and fitness.

Do you think race directors will have tighter security in the future?

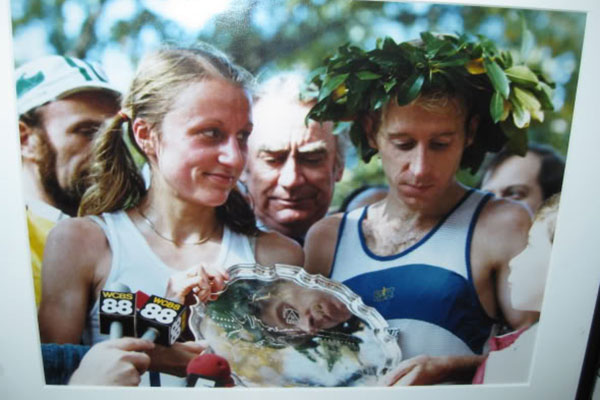

This weekend I was at a fairly new marathon down in Roanoke, Virginia, called the Foot Levelers Marathon. I ran a relay leg there with Frank Shorter, the Olympic gold medalist, Bart Yasso from Runner’s World, and two people who are new runners. But they had more security down there. I noticed that as we were going from one area of the marathon to the finish line—there were cops checking people’s purses and bags. And I also know the London Marathon this past weekend had many more police and security and increased camera security. I think Boston and all the major city marathons will eventually have an immense amount of cameras, particularly in heavy crowd-concentrated areas. There will be more bomb-sniffing dogs.

“I’ve got emails from across the country—from friends, from old teammates, retired runners who haven’t raced in 10 years, and they all say, I’m going to run next year.”

What does the marathon mean for the city of Boston? You’ve run marathons in every corner of the world. How is Boston different?

I’ve run all over the world. But Boston! The people love this race simply because it’s Patriots’ Day. It’s a family holiday. The people of New England know marathons, because it is the oldest one. There’s a lot of lore related to the Boston Marathon in the same way there’s a lot of lore related to the Boston Red Sox. But it’s more than that. Wherever you live! If you live in Detroit, you love the Detroit Marathon. Miami? You support the Miami Marathon. Santa Barbara—you support the Santa Barbara Marathon. Marathoning is all over now, and it’s a new place to find yourself and explore yourself.

How much has the Boston Marathon changed since you were ruling the roads in the ’70s?

It’s changed from night to day. When I won in 1975 there were about 2,000 runners in the race. There were far fewer women. And there was no prize money! But the crowds were still there. After all, it was already an 80-year-old race.

Running is wildly popular now. How has its place in culture evolved since the running boom?

Running has become an accepted sport in America and around the world. So that’s changing things rapidly around here. Also, people are running to fight diseases like cancer, for example. Or to fight Alzheimer’s. I think a lot of times runners and cyclists and so forth are playing a huge role in America’s awareness about how to fight these diseases. You can do something. You don’t have to be on the sidelines. That’s what I love about our sport. It’s the inclusive sport. We’re not like the other sports that close the door to just about anybody. In this one, the door’s open.

The city of Boston is resilient and Bostonians have long memories. What will the lasting effect of last week’s events be on the marathon?

It’s bigger than the marathon. Yes, I think they’re going to have improved security, but I think it’s going to bring people together. I’ve got emails from across the country—from friends, from old teammates, retired runners who haven’t raced in 10 years, and they all say, I’m going to run next year. Fifteen Boston marathon champions have been organized by Amby Burfoot, the ‘68 winner, to run next year. They’re going have to enlarge the size of the field!

When I think of this event, I think of the eight-year-old kid who lost his life. He’s just a kid. That shouldn’t happen for any reason. I think it’s going to be different. It’s going to be somber in a way. But there is a purpose among many people coming back to unite in this very patriotic event. It’s going to get some of us to work harder! We’re going to get some blisters and some aching legs—but we’re going to try to get to the starting line.