If you’re a gambler, you might have noticed that the prediction market known as Intrade shut down last week. Theories abound as to why that happened. It’s not clear what will become of Intrade—perhaps it will be back up next week, perhaps we will never see it again. But I wanted to mention some of Intrade’s contributions to politics. (At the risk of being presumptuous, I’ll be referring to Intrade in the past tense, although I’ll be happy to be wrong about that.)

If you never used it, Intrade was really a clever gambling device, allowing you to bet on the probability of an event occurring. You establish an account and put some money in it. Then you look among hundreds of different betting “contracts” (who’s going to win the presidency, who’s going to win American Idol, will US GDP growth average above 3 percent this year, etc.) and decide where to place your money. Surer things were more costly bets. But you could buy and sell a contract any time prior to the event. So, for example, if you had bought an Obama re-election contract on May 1, 2011 (then valued at about 60) and then sold it on May 3, 2011, the day after Bin Laden was killed (when the contract was valued at about 70), you’d have turned a tidy profit.

Should we buy options on presidential candidates?

Can you run a government with prediction markets?

Beyond the gambling fun, Intrade was believed to be very useful for those interested in forecasting elections. Polls have the disadvantage of being meaningful and accurate only within a few months—or weeks—of an election, since most voters aren’t well aware of the candidates or issues until then. By contrast, people betting on political events are a self-selected group of highly informed political observers, people with enough interest and confidence in their knowledge to actually put down money. In theory, at least, these folks should be able to provide much more reliable predictions much earlier in the race. And, indeed, some studies (like this dissertation by Ian Saxon) have found early political betting markets to be better predictors than early polls. Robert Erikson and Christopher Wlezien, however, note that markets and polls aren’t actually measuring the same thing, and that when properly compared, polls tend to do a better job forecasting.

Part of the problem with using markets like Intrade to forecast elections is that they may be subject to short-term manipulation, which compromises their predictive value. For example, back before banking laws made it prohibitively difficult for Americans to place bets on Intrade, I made a few. I made a bit of scratch (i.e., enough to buy a high-end Frappuccino) by betting on Hillary Clinton to win the 2008 Democratic nomination right before the Ohio primary (which she was expected to win) and then selling that contract the day after. I did the same with Mitt Romney right around the Michigan primary that year. (I also lost a few dollars here and there.) Notably, I did not think that either Clinton or Romney would win their respective parties’ nominations that year. I was just betting that enough other people would think that to briefly raise the value of their contracts, and it worked.

And that, of course, was part of the problem, if you were trying to use Intrade to actually estimate a candidate’s chances of winning a contest. My purchases slightly distorted the value of the contracts, and if enough other people were doing that at the same time, it just ended up inflating the candidates’ apparent chances of winning after a day of good news, even though their chances really hadn’t improved.

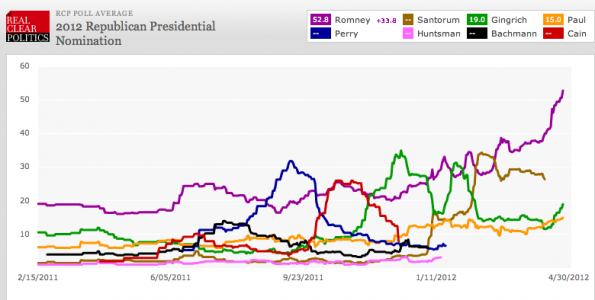

More generally, it turned out that people who bet on Intrade were subject to the same biases and impressionability that people surveyed in polls were. Or worse: as Josh Tucker notes, bettors may have been just relying on polls in placing their bets. Take an example from the 2012 Republican presidential nomination contest. Below is a chart from Real Clear Politics showing the poll standings of the Republican candidates. It was an odd contest in that almost every candidate saw some time as a front-runner. Note in particular Newt Gingrich (in green), who had two poll surges, one in late 2011 and the other in early 2012:

Now note Gingrich’s Intrade contract from the same time period. Basically, he sees the exact same double-surge pattern.

Now what, in fact, were Gingrich’s actual chances of winning the Republican presidential nomination in 2012? Virtually zero! He had almost no endorsements, most of the Republicans who served with him in the House were not only not backing him but actively opposing him, he had a history of flip-flopping on key Republican issues, he hadn’t served in office for over a decade, he had loads of personal baggage, etc. Either he never had a shot, or everything we knew about presidential nominations was wrong. Ideally, the markets should have reflected that, and should not have been so easily impressed by a few weeks of good press for him or a strong debate performance. But the markets proved as fickle as poll respondents.

So, if Intrade comes back on line, or if you want to use another site like the Iowa Electronic Markets, by all means have fun with it, but just know that you’re not necessarily getting any inside dope on the next election by watching people bet.