Within hours of the killings this week of four Americans diplomats, including U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens, in Libya, more than a dozen blog posts popped up around the internet asking, “Who is Sam Bacile?” It was a natural question to pose: “Bacile” is the pseudonym of the filmmaker behind The Innocence of Muslims, an American-made video whose insulting depiction of the prophet Mohammed appears, at this point, to have incited anti-U.S. riots in Benghazi, Cairo, Tehran, and Sana’a, Yemen. It now appears, however, that the attack on the diplomatic mission in Libya was a planned assault by religious extremists, who used the protests as cover to murder the four Americans. As truly awful as his film is, “Sam Bacile” appears to be at least something of a patsy. Moreover, there’s another important way in which the American media and political classes, in their focus on The Innocence of Muslims, have missed the forest for the trees.

A scene from the YouTube version of the “Innocence of Muslims,” which has been seen as the spark for recent attacks on U.S. diplomatic posts in the Muslim world. Is food insecurity the tinder for this blaze?

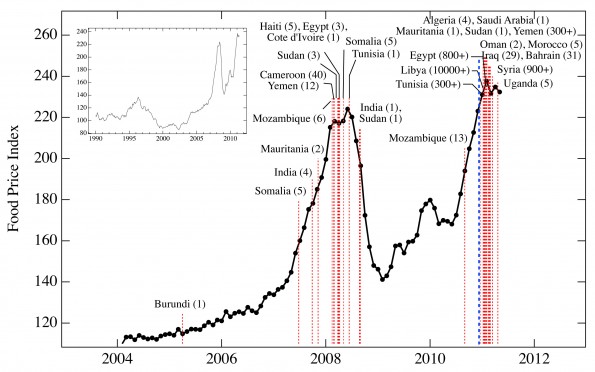

In cases of broad social unrest, catalytic incidents are important insofar as they take the measure of people’s passions and attach a vivid narrative—a shot heard ‘round the world—to a mass movement. But wood has to be dry for a spark to catch; populations of people have to be primed for unrest. And in both the run-up to the Arab Spring and now, a research team at the New England Complex Systems Institute has demonstrated convincingly, that priming factor is skyrocketing food prices.

A study released by the team under the direction of professor Yaneer Bar-Yam in September 2011 (PDF) charted fluctuations in global food price since the financial crisis of 2007-8 and showed that, with each successive peak, citizens in food-importing countries reliably destabilize the political leadership. “When food prices go up,” Bar-Yam told me this spring, “when food becomes unavailable, people don’t have anything to lose. That’s when social order is itself affected.” The most recent such peak came in late 2010-early 2011 and yielded what is commonly called the Arab Spring.

The Food Price Index from January 2004 to May 2011, superimposed over a timeline of global mass unrest. Red dashed vertical lines correspond to the start dates of “food riots” and protests associated with the major recent unrest in North Africa and the Middle East. The overall death toll associated with each event is reported in parentheses. (Click to enlarge)

Bar-Yam also told me that the team’s model predicted another massive food price spike this fall/winter, even bigger than the last. This foreseeable crest was only exacerbated and expedited by this summer’s drought- and heatwave-bred corn disaster. And, indeed, the World Bank recently announced that food prices have reached record highs worldwide. As predicted, we have begun to see the concomitant rise in political instability in various forms, including riots and strikes.

As critical as it is to consider food price vacillations when contemplating this wave of political instability, it is perhaps even more important to understand why food price is spiking and plunging so dramatically—and so reliably. Bar-Yam’s team released another study dealing with this question, also in September 2011, attributing careening food price to a combination of state subsidy of agribusiness in the United States and commodities speculation.

Specifically, agricultural subsidies from the federal government put tremendous downward pressure on food prices, undermining agriculture in, above all, the Middle East and North Africa, and making countries there big food-importers, dependent on the global commodities market. These circumstances in place, if the food price were to spike for some reason, the result would be, in Bar-Yam’s words, “worldwide catastrophe in terms of food availability.”

The passage in 2000 of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, (PDF) one of the Clinton Administration’s final acts and one for which Mr. Clinton has subsequently apologized (if not atoned), allowed for exactly such a spike. The law not only effectively banned regulation of the derivatives market, but also opened the commodities market to speculation, price bubbles, and manipulation. Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank and others made big profits by creating “index funds,” essentially allowing any old investor to buy commodity futures, an option previous open only to so-called bona fide commodities traders, including airlines purchasing future fuel and farmers selling a future crop.

So when, after the mortgage crash, speculators needed somewhere to put their money, huge amounts of capital flooded into the relatively small commodities market, creating the unstable situation now on display in the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and, by extension, the plazas of Cairo, Benghazi and elsewhere.

It didn’t help that in 2005 the government began to subsidize the conversion of corn to ethanol, diverting food for fuel, and itself leading to dramatic price increases. Today over 40 percent of U.S. corn is used in this way.

In the era of transnational capital, domestic policy is foreign policy. Onlookers baffled by the violence erupting in the Middle East would therefore benefit by spending less time inspecting the straw that broke the camel’s back—and I believe more camel’s backs are likely to break soon—and more time scrutinizing the activity on Capitol Hill, Wall Street, and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.