When Luiz Rocha, a fish biologist at the California Academy of Sciences, goes scuba diving, he tacks on one and a half times his body weight in specialized diving gear. Once he submerges, he can’t spare a moment to take in the vibrant corals just beneath the surface—he has greater depths to plumb.

Rocha is headed toward what Smithsonian Institution fish biologist Carole Baldwin calls “a very diverse and productive portion of the tropical ocean that science has largely missed”: mesophotic reefs. “Mesophotic” is Greek for “middle light,” referring to the intermediate amount of sunlight that can penetrate to depths of 100 to 500 feet below the ocean’s surface.

The dives required to reach mesophotic reefs are as technical as they are deep. Strapped to a larger-than-average gas tank, Rocha uses the rebreather method, recycling the air he breathes as he goes.

The coral species from shallower reef communities begin to taper off around 90 feet into Rocha’s dive. At 330 feet, the water chills significantly. This is the thermocline, defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration as the transition layer between the sunlight-warmed water at the surface, and the colder water below.

From this depth on, Rocha has just 15 minutes before decompression sickness becomes a risk. In the liminal space of the mesophotic zone, with all the time it takes to unload a dishwasher, Rocha and his colleagues survey the flora and fauna of the reef system.

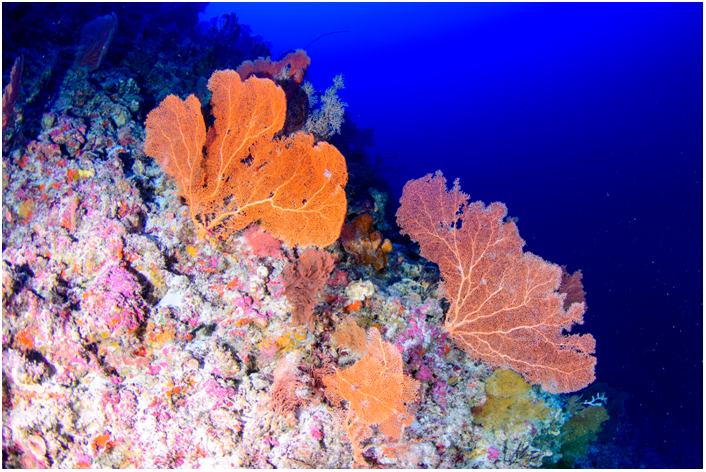

In the low light of a mesophotic reef, he finds a diverse array of corals, albeit not as recognizable as their shallower counterparts. Instead of the stony, horizontally spreading tabletop structures common in shallow reefs, there are myriad soft corals that grow in branches, similar to trees. There are some hard corals, too, but these are solitary, instead of the large colonies closer to the light. In all, the mesophotic hosts a dizzyingly diverse community of corals, sponges, and algae. This distinct habitat is occupied by unique species of fish and invertebrates, many of them not yet described by science.

“We find mesophotic reefs at the same places where there are shallow reefs,” Rocha says. “My best estimate is that there are just as many mesophotic as there are shallow.”

Yet scientists know comparatively little about mesophotic reef systems, perhaps because they are so difficult to reach. Now, a new study by Rocha and his colleagues, published in the journal Science, hopes to shine more light on this perpetually dim ecosystem—and overturn some long-held assumptions.

The Mesophotic Lifeboat?

Researchers have long considered mesophotic reefs as potential refuges, or lifeboats, for fish and coral species. Since mesophotic reefs are perceived to be less affected by threats at the surface than shallow-water reefs, scientists theorize that they may provide a buffer of sorts against damage to shallow reefs: coral and fish populations that are harmed at the surface could be replenished by those living at greater depths.

But the results of Rocha’s study question this view.

“There is species overlap, but not much,” he says. “There are several species of coral that survive within mangroves during bleaching events, but nobody says that mangroves are a lifeboat because species overlap is low and because mangroves are also threatened.”

Baldwin also challenges the theory, saying there are unique communities of fish in reefs of all depths: shallow, mesophotic, and the deeper zones, called rariphotic. This means that fish are often adapted to specific depths and rarely move between them.

“As such, the refugia hypothesis is not supported,” she says.

The lifeboat hypothesis postulates that the decline of shallow-water, or altiphotic, species of corals and fish affected by storms, climate change, ocean acidification, and fishing pressure will be buffered by deeper, mesophotic reefs.

It also implies that mesophotic reefs are less affected by climate change due to their depth, thereby maintaining their fitness and providing a fallback as shallow reefs decline. However, as the new study details, mesophotic reefs are also threatened and made vulnerable by ocean acidification, warming sea temperatures, and increased storm damage, all linked to the massive increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Ocean acidification, driven by sharp increases in carbon in the oceans, weakens corals, and makes them more vulnerable to bleaching and disease, as do rising sea surface temperatures and storm damage. Rocha and his team discovered mesophotic reefs in Hurricane Matthew’s path in the Atlantic were buried by sediment in 2007 and exhibited signs of extreme damage due to a cascade of debris from the shallows. Signs of hurricane and cyclone damage to mesophotic reefs have also been recorded in the Great Barrier Reef off Australia and elsewhere by past studies.

Complex Interactions

Rocha’s team conducted visual censuses of mesophotic coral reefs all around the Pacific and western Atlantic oceans. They found a strong disconnect between reef community composition at shallow and mesophotic depths. A majority of reef fish species that live at mesophotic depths live only at those depths. The same is true, to a somewhat lesser degree, of shallow coral species.

Kimberly Puglise, of the NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, has studied certain fish species whose movements support the lifeboat hypothesis. While conducting a NOAA study looking at the role that mesophotic reefs play in replenishing key species to the downstream shallow reef ecosystems of the Florida Keys, Puglise and colleague found that one of their focus species, the red grouper, displayed continuous population structure between shallow and mesophotic reefs. For Puglise, species like the red grouper demonstrate a direct connection between shallow and deep ecosystems.

“Every new study provides a new data point to better understand these ecosystems,” she says. “In my opinion, it is too early to state anything definitively about whether these ecosystems can or cannot serve as a refuge for shallow reef species.”

Rocha agrees that there’s still much to learn about mesophotic reefs.

“Every time we go to those depths we find new species,” he says, “We [recently] published another one.” The subject of that study, the Aphrodite anthias, is a small pink-and-yellow fish that Rocha and a colleague, Hudson T. Pinheiro, spotted at a depth of 400 feet. They named it after the Greek goddess of love and beauty, saying it had enchanted them “much like Aphrodite’s beauty enchanted ancient Greek gods.”

Rocha says he hopes that exciting discoveries like those of new species will generate public interest and garner support for coral reef conservation, at all depths.

“The sheer number of discoveries of new species of marine life is exhilarating,” says the Smithsonian’s Baldwin, who earlier this year published a report describing a new layer of the ocean deeper than the mesophotic, called the rariphotic (“scarce light”).

The Ultimate Lifeboat

Shallow and mesophotic reefs alike are vulnerable and declining worldwide. Coral reef conservation is an intricate process due to the varied threats posed by overharvesting, pollution, invasive species, and disease. However, Rocha says the greatest threat to coral reefs everywhere is clear: climate change.

“Everything else we do … might buy corals time but won’t solve the problem,” he says, referring to conservation actions such as creating reserves, restoring coral, or banning plastics. To reverse the decline of reefs at all depths, global action must be taken to slow the changing climate, he says.

If there is a lifeboat for coral reefs, whether shallow or deep, it’s humans who hold the key.

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.