THE MORASS THAT IS CALIFORNIA POLITICS today may have originated in mid-January of 1896, when a middle-aged man boarded an eastbound train in Oakland. With his ex-soldier’s ramrod bearing and his red-gold hair turning gray, the traveler was not likely to have gone unrecognized. He was Ambrose Bierce, the West’s most famous newspaperman, who used his San Francisco Examiner column to skewer fools and rogues, as well as to coin the acerbic definitions later collected in his Devil’s Dictionary. (Example: “PEACE, n: In international affairs, a period of cheating between two periods of fighting.”)

Although the conservative Bierce admired businessmen, he was en route to Washington DC to lead a SWAT team of journalists, cartoonists, and accountants in an effort to prevent California’s most powerful corporation, the Central Pacific Railroad, from doing what American capitalists so love to do: obtain a favor from Congress.

Bierce was overriding his instincts for two reasons. First, his boss, Examiner publisher William Randolph Hearst, a Democrat, had asked him to go after the railroad, which had long been identified with the Republican Party. Hearst not only paid Bierce a handsome salary but also let him write what he pleased. Bierce couldn’t deny that Hearst had earned the right, for once, to draft him for a pet cause.

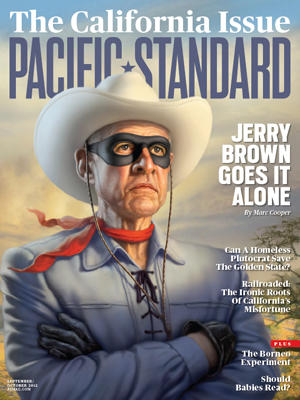

California Issue

Other stories in Pacific Standard‘s special look at California’s effort to live up to its sobriquet of the Golden State include:

The Governor’s Last Stand

The Freethinking Homeless Billionaire and the Flat-Broke State

The Third Act: Professor Schwarzenegger

Then, too, Bierce loathed dishonesty more than he revered capitalism. Backed by generous federal subsidies, the Central Pacific came into being as a segment of America’s first transcontinental line, linking up with the Union Pacific at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869. In the process, the Central Pacific’s owner-builders—Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford, and Charles Crocker, known as the Big Four—had each siphoned away a private fortune of about $20 million from the federal pot. By ’96, death had reduced the Big Four to a Big One, but the 74-year-old Huntington was overbearing enough for four. In pitting the pugnacious columnist against the notorious robber baron, Hearst was practically doing Bierce a favor.

Huntington couldn’t help but take notice of Bierce’s journey—it had been trumpeted on the Examiner’s front page. But Huntington had deep pockets, a couple dozen lobbyists at his disposal, and the ear of the Republican Party, which controlled both houses of Congress. What’s more, the issues involved were geographically remote and hard to understand: In addition to land, the subsidies had consisted of federal bonds handed over to the railroad to sell as its own certificates. Those bonds—with interest, the tab added up to roughly $75 million—were now coming due, and the Central Pacific sought to postpone repayment to the United States for 75 more years. Huntington reckoned that Congress wouldn’t want to dwell on such distant complexities for long.

Out in California, the Progressive movement was making some noise, but Huntington was accustomed to having his way in the Golden State. He saw no reason why it shouldn’t be the same at the national level.

Huntington was about to learn how mighty the pen can be, and the Progressive movement would take heart from the outcome. Yet given the current state of governance in California, it’s fair to say that the railroad tycoon had the last laugh.

BORN IN 1842, Ambrose Bierce grew up in rural Indiana, where he cultivated a deep love of reading. When the Civil War broke out, Bierce joined the Ninth Indiana Volunteers. He was a distinguished cartographer and aide to a general, until he took a bullet in the head during the 1864 Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. He recovered, and his time in action ended shortly thereafter. After the war, he fetched up in San Francisco, where he tried his hand at writing. Bierce’s Civil War tales exude authenticity because he, almost alone among 19th-century American fiction writers, could draw upon firsthand knowledge of combat. In the 1870s, he found a niche as an elegant gossip columnist, a forerunner of Herb Caen and his “three-dot journalism.”

In 1887, at a point when Bierce’s career was stagnating, Hearst beckoned. Newly installed as the publisher of a newspaper that his millionaire father had given him as a present, the young mogul wanted to make a splash in journalism, and who better than Bierce to send water flying? At the Examiner, Bierce consolidated his position as the West Coast’s chief scourge of blockheads and knaves, the Big Four very much among them.

Huntington, Stanford, Hopkins, and Crocker were all Easterners lured by the Gold Rush to California, where they quickly realized that the surest way to succeed was not by prospecting but by selling prospectors what they needed. All four settled in Sacramento, where Huntington and Hopkins met and became partners in a hardware store, Stanford sold groceries, and Crocker peddled dry goods. They also had in common their opposition to slavery, allegiance to the Republican Party, and outsized ambition. In the early 1860s, they saw merit in a scheme proposed by an engineer named Theodore Judah. At the time, everyone paid lip service to the idea of connecting the American West and East by train, but Judah had gone so far as to scout the least troublesome route over the Sierra Nevada.

Judah died of yellow fever in 1863, but his know-how had helped persuade Congress to subsidize the grand project. The Big Four carried on without him. Stanford was the group’s unctuous figurehead, Hopkins the geeky bookkeeper, Crocker the swaggering construction manager, and Huntington—operating out of New York and Washington—the crafty fund-raiser and influence-peddler.

They entered into a race from opposite directions with the Union Pacific (the more miles of track laid by a railroad, the larger its share of the federal subsidies). On the way, both sets of owners had the same underhanded idea: they should establish a construction firm, ostensibly independent, but in fact owned by them. After steering construction contracts to the new company, they could pay themselves fat dividends on the sly. The Union Pacific came to grief when it was learned that the firm had bribed members of Congress, in what became known as the Crédit Mobilier scandal. Hopkins made sure that the Central Pacific eluded scrutiny—by destroying the company’s ledgers—but his efforts accomplished only so much.

For a while, the Big Four had a fifth partner, David Colton, who bought his way into the Central Pacific but never paid his full share. After his death in 1878, the surviving partners tried to collect from his widow, who fought back by releasing damning letters to the press. Spelled out for all to read were Huntington’s recommendations that Colton stoop to such methods as bribing state legislatures to enact pro-railroad bills.

In California, strategic payments gave the railroad such a stranglehold that when a state constitutional convention established a commission to regulate the railroad, the Central Pacific managed to dominate it, too. Nor was the corporate image burnished when three of the Big Four built gaudy mansions on San Francisco’s Nob Hill. A magazine cartoonist played upon the company’s growing unpopularity by depicting it as an octopus whose tentacles were squeezing the life out of various sectors of the California economy. (Frank Norris was to borrow that motif for his muckraking novel about a thinly disguised version of the Central Pacific, The Octopus, published in 1901.)

Still, the railroad’s power remained intact. In early 1896, Huntington and his lobbyists sought to punt repayment of the company’s federal debt well into the next century, and few sporting men in Washington would have bet against them.

Once he reached Washington, Bierce set up shop in a hotel near the White House. He faced two challenges. He had to master a wealth of factual, financial, and legal material that Huntington and his minions already knew intimately. And he had to make Easterners care about a subject removed from them by three decades and three thousand miles. Hearst stood ready to bankroll a special Washington edition of the Examiner. Printing it was one thing, however; getting people to read it was another. Bierce’s job was to fill that special’s pages with cogent, sparkling copy.

He had some advantages, though. He lived in an age when verbal combat was a much-practiced art—words didn’t just ring out; they slapped, kicked, gouged, and pulled hair—and there was no better word warrior than Bierce. Nor, as Huntington’s forces soon discovered, was he slow to take advantage of an opening.

In early February, the Huntington-friendly Washington Post reprinted a telegram in which a number of prominent Californians endorsed the railroad’s bid for debt postponement. As it turned out, however, some of the nabobs listed as signers had never even heard of the telegram and in fact, their views were quite the opposite. Bierce gleefully devoted several articles to this sloppy work by Huntington’s staff.

Soon he was launching broader attacks. He cited facts and figures, but above all he flexed his rhetorical muscles. Here, for example, is his diatribe against Huntington after the old man testified before a House committee:

Mr. Huntington is not altogether bad. Though severe, he is merciful. He tempers invective with falsehood. He says ugly things of his enemy, but he has the tenderness to be careful that they are mostly lies…. Mr. Huntington’s rancor blown about in space as a pestilential vapor will outlive all things that be. It is his immortal part.

Elsewhere in the same piece, Bierce summed up Huntington as “an inflated old pigskin.”

Before long, le tout Washington couldn’t wait for its daily dose of salty witticisms at Huntington’s expense. Bierce had succeeded admirably in calling attention to the railroad’s scheme. Meanwhile, the California congressional delegation lined up against the railroad, with one exception: a Democratic representative named Grove Johnson, whom Bierce mocked as a hireling of the railroad. At one hearing, Bierce wrote, Johnson “modestly bent his goatlike head and emitted a faint odor of violets.”

Huntington met with another setback after an antirailroad senator questioned him at length about how much he’d invested at the dawn of the project. (The idea was to highlight the disparity between how little he had put in, and how much he had taken out.) Lots and lots of money, Huntington replied, the implication being that his great wealth was justified by the risks he’d taken. Then the senator sprang his trap, giving Huntington copies of his Sacramento tax records for the early 1860s. They exposed him as a man of decidedly modest means. “It was obvious that the old man had been caught in rank perjury,” Bierce commented.

But the Republican majority stuck with Huntington, until he pushed his luck by asking Congress for a second favor—to referee a conflict between Santa Monica and Los Angeles over the location of a deepwater port for Southern California. Huntington favored Santa Monica, and it soon became clear why: he owned land there, and a port would surely multiply the land’s value. Bierce jumped all over this “coincidence,” which, unlike the matter of the Central Pacific’s federal bonds, was easy to comprehend. Bierce’s next story was headlined “Another Thieves’ Scheme on the Pacific Coast.”

In California, leaders of the state Republican Party took note of Bierce’s scathing and relentless reports. For the sake of its candidates in the upcoming fall elections, the party made a dramatic decision: to break with Huntington and oppose his railroad bill. The national party deferred to its California offspring, and with that—five months after it had started—the game was over. Congress ultimately settled the matter by ordering the Central Pacific to retire its debt within 10 years, and Bierce and Hearst were lauded as giant-killers.

Emboldened by Huntington’s defeat, California Progressives went on to score impressive victories, notably the election of their man for governor in 1910. His name was Hiram Johnson, and in a twist that almost defies belief, he was the son of Grove Johnson, the congressman whose steadfast support of the railroad in 1896 had left him odd man out in the California delegation. Governor Johnson pushed through a series of measures to bring railroads under control, as well as state constitutional amendments authorizing the initiative, referendum, and recall.

OF ALL THE BIG FOUR’S SINS, the most grievous was its poisoning of the California body politic. The Progressive-era safety valves were put in place to assuage the widespread fear that big money had swamped government and left the normal checks and balances unable to loosen corporations’ grips on the levers of power. A century later, however, the perverse effect of that “cure” has been to hobble the state, which finds itself drowning in deficits, furloughing its employees, beggaring its educational system, and sometimes going for months on end without a budget.

As they were designed to do, initiatives bypass the normal legislative process by which, as bills are refined and debated, diverse interests get to have their say. Instead, voters are presented with up-or-down votes on what are typically raw and rigid proposals. And in an irony that the Big Four might have appreciated, gathering signatures to put an initiative on the ballot, buying ads to influence voters, hiring lawyers to contest alleged defects in an election—all of these tasks have become so costly that large corporations and well-heeled interest groups enjoy a decided advantage whenever a measure touches upon their prerogatives. In 1996, for example, an initiative to establish a no-fault insurance system for motor-vehicle accidents drew the ire of trial lawyers, and they opened their wallets to beat it. In 2005, after a disastrous experiment in deregulation of the state’s electric utilities, the utilities poured millions of dollars into defeating an initiative to reimpose strict regulation. Big money, in short, still has California over a barrel, just as it did in the Gilded Age.

The state is a prisoner of its own reforms, especially those traceable to the frustration people felt in the late 19th century over how single-mindedly, and with so little regard for ethics, the Central Pacific worked its will. A healthy representative government should be able to do without the initiative, referendum, and recall. Today it can be argued that California government will never fully regain its health with them.

WHILE IRONIC, of course the state’s current troubles can’t be blamed on Bierce or Progressives; they were only trying to save their state. One thing seems clear now, however: among the actors in the 1896 drama, the defeated Huntington is the one who left the deepest, and darkest, imprint on the state.

This article is adapted from Dennis Drabelle’s new book, The Great American Railroad War: How Ambrose Bierce and Frank Norris Took on the Central Pacific Railroad, published in August by St. Martin’s Press.