New research finds that rising sea levels due to climate change will put dozens of World Heritage Sites in the Mediterranean region at increased risk of flooding and erosion—threats many of the sites are already facing.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization has recognized 1,092 cultural and natural heritage sites under the World Heritage Convention since 1972. Nearly 80 percent of those sites are cultural World Heritage Sites “considered to be of outstanding value to humanity,” according to UNESCO.

Flooding and coastal erosion due to rising sea levels could be a threat to a number of those culturally important sites. The authors of a study published in the journal Nature Communications in October write that a “large share of cultural [World Heritage Sites] are located in coastal areas as human activity has traditionally concentrated in these locations.”

Previous research has looked at the local-scale effects of natural hazards like landslides and river floods as well as various climate change impacts on particular UNESCO World Heritage Sites without taking climate change directly into account, and no studies have specifically assessed the risks of coastal flooding due to storm surges or coastal erosion due to sea-level rise, the authors note in the study.

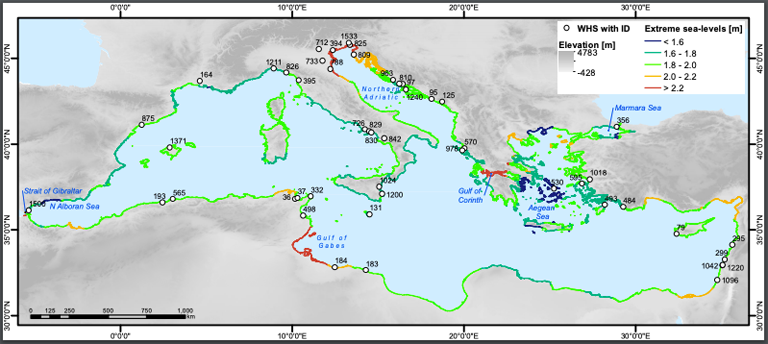

To address this knowledge gap, a team led by researchers at Germany’s Kiel University considered the future of 49 cultural World Heritage Sites in low-lying coastal areas of the Mediterranean—places like the Venetian Lagoon, the Old City of Dubrovnik, and the ruins of Carthage—under four different sea-level rise scenarios. In order to evaluate the potential risks to each of the sites, the research team created a spatial database of the 49 World Heritage Sites that included the location and form of the sites in addition to other information, such as the site’s distance from the coastline and whether it was situated in an urban or rural setting.

“Using this database and model simulations of flooding, taking into account various scenarios of sea-level rise, we were able to develop indices: the index for flood risk and for erosion risk,” lead author Lena Reimann of Kiel University said in a statement.

(Photo: Nature Communications)

The vast majority—47 of the World Heritage Sites studied—were found to be potentially threatened by coastal erosion or storm surges by the end of the century. Specifically, 37 of the sites were found to be at risk from a 100-year flood or storm surge, and 42 to be at risk from coastal erosion. Just two of the sites studied, Medina of Tunis and Xanthos-Letoon, were found not to be facing any risk from either of those two hazards by 2100.

The study also showed that “93% of the sites at risk from a 100-year flood and 91% of the sites at risk from coastal erosion under any of the four scenarios are already at risk under current conditions, which stresses the urgency of adaptation in these locations,” Reimann and team write.

The risk to these Mediterranean World Heritage Sites will only increase over the course of the 21st century, with the magnitude of that increase depending on the rate of sea level rise. “In the Mediterranean region, the risk posed by storm surges, which are 100-year storm surges under today’s conditions, may increase by up to 50 percent on average, and that from coastal erosion by up to 13 percent—and all of this by the end of the 21st century under high-end sea-level rise,” Reimann says. “Individual World Heritage Sites could even be affected much more due to their exposed location.”

That 50 percent increase in flood risk and 13 percent increase in erosion risk is based on an average sea-level rise in the Mediterranean region of 1.46 meters or about 4.8 feet by the year 2100, which has a 5 percent chance of happening under a high-end climate change scenario. “Even if such a high sea-level rise has a low probability of occurring by the year 2100, this scenario cannot be ruled out, due to the high uncertainties in relation to the melting of the ice sheets,” co-author Athanasios Vafeidis, a professor at Kiel University, said in a statement. “In addition, such a scenario is quite relevant from a risk management perspective, since a 5% probability in this context is not low.”

World Heritage Sites are protected under the World Heritage Convention, but managing the sites and adapting them to endure the effects of climate change is the responsibility of countries. Management plans rarely include strategies for adapting to the effects of sea-level rise, however, according to Reimann and team.

“Our results provide a first-order assessment of where adaptation is most urgently needed and can support policymakers in steering local-scale research to devise suitable adaptation strategies for each [World Heritage Site],” the researchers write. “Additionally, based on the [World Heritage Sites] most at risk policymakers can designate priority areas for further analysis in order to devise specific adaptation strategies.”

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.