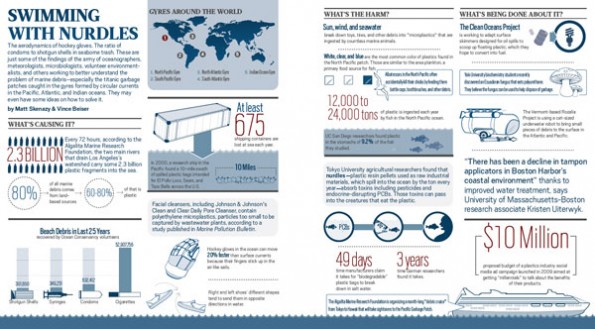

Our oceans are filled with trash. Oceanographers, environmentalists and biologists have been working for years to better understand the problem of, and solutions to, marine debris. In the current issue of Pacific Standard we highlight the problem of, and some possible solutions to, marine debris in “Swimming with Nurdles” (PDF).

Add to that:

- Marine debris is easy to think of as an environmentalist’s problem. But, according to an Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation report, marine debris cost Pacific nations’ fishing, shipping and marine tourism industries $1.27 billion in 2008.

- Most of the trash in the ocean comes from land, and a majority of that is plastic. One solution: use less plastic products, specifically the single use ones. After Ireland imposed a 15-cent tax on plastic bags, annual per capita use dropped from 328 to 21. The public loved the tax! “It would be politically damaging to remove it,” argue researchers in Environmental and Resource Economics. Similarly, in 2008, when China banned the free distribution of plastic bags, shoppers cut their usage in half.

- A new study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters says that wind has been blowing light pieces of plastic down into the water column, causing researchers to underestimate the amount of plastic in the ocean. How much worse is it? Data collected from just the surface of the ocean underestimates the total amount of plastic in the ocean by an average factor of 2.5. In some cases estimates might by off by as much as a factor of 27.

- In 1965 Jim Ingraham of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center began work on the Ocean Surface Currents Simulator (OSCURS), which traces the surface currents of the North Pacific. The model is based on current data from Navy ships across the Pacific. OSCURS was developed to study how the currents effect fish eggs and marine mammals, but Ingraham and oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer have also used the model to predict where trash spilled off huge shipping liners—anything from Nike’s to rubber ducks—would end up. Run your own tests here.

- The salt water of the world is constantly in motion, carrying debris around the globe. Flotsam from San Francisco can reach the North Pacific Gyre in as little as six months, according to Ebbesmeyer. Debris from Asia can take nine months to two years.

- A soccer ball washed ashore in Alaska is the first piece of debris from last year’s tsunami that can be returned to its owner, Reuters reported on Monday. The ball washed ashore with markings from the Osabe School in the Iwate Prefecture, according to officials with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The U.S. State Department is now working on a way to get the ball back to its rightful owner.