Conventional wisdom suggests that states are better-served in Washington by elected officials who can stay there long enough to accumulate power, get things done, and funnel home some of that government largesse. The longer an incumbent serves, the higher he or she rises in party ranks, and the more likely constituents will benefit. (The people of Maine, for instance, may be bigger losers than the GOP following the retirement announcement this week of long-serving and well-respected Senator Olympia Snowe.)

There is new research, however, that suggests really powerful politicians may actually have a negative impact on their state economies back home. To explain how the researchers arrived at this counterintuitive conclusion, it’s helpful to start from the beginning.

“The hypothesis was essentially to test the impact of government spending on economic activity. We didn’t know which way that was going to go,” said Chris Malloy, an associate professor at the Harvard Business School and one of the study’s authors. Would government spending help local businesses or hurt them? And how do you know what results are attributable to the economy itself and which are caused by the influx of government cash?

“The experiment you want to run is what if you randomly just dropped cash onto a country or a state,” Malloy said. “What would happen?”

Miller-McCune’s Washington correspondent Emily Badger follows the ideas informing, explaining and influencing government, from the local think tank circuit to academic research that shapes D.C. policy from afar.

He and his co-authors Lauren Cohen and Joshua Coval eventually realized there is a real-life scenario that mimics this cash-drop-from-a-helicopter: it’s basically what happens when an incumbent ascends to a powerful committee chairmanship in Washington.

Politicians who chair the most influential committees — such as Finance and Appropriations in the Senate or Ways and Means and Appropriations in the House – have the greatest ability to funnel earmarks and government contracts to their constituents. Chairmanships are given to the most senior elected official on a committee in whichever party currently controls the House or Senate. This means the positions shuffle every time a committee chair retires, or loses an election, or if the entire chamber changes parties – but not because of anything to do with the economy back home.

“It’s completely unrelated to anything happening to your state when a guy in Montana steps down,” Malloy said. “That has nothing to do with the economic activity in your state when you’re in Mississippi.”

This scenario presents researchers with the opportunity to look at the economic impact at the state level of what happens when federal money suddenly floods in (and for reasons that have nothing to do with, say, stimulus during a recession).

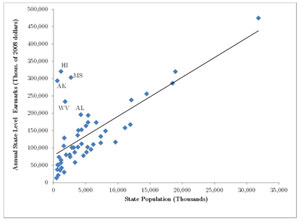

Generally, states receive earmark money that’s closely correlated with the size of the local population. The authors illustrate this relationship with the following chart in their paper, which is published in the Journal of Political Economy.

This graphic demonstrates how states receive earmark money that’s closely correlated with the size of the local population.

But a few states — Hawaii, *Alaska, Mississippi, West Virginia, and Alabama — stand out. “Anecdotally,” Malloy said, “you look at that chart and say, ‘What’s unique about all those states?’”

As it turns out, they’ve had powerful politicians in Washington who sent home more money than might normally be their due. Malloy and his colleagues found that in the year following a politician’s appointment to a powerful committee, states experience an increase of 40-50 percent in earmark spending, and a 24 percent increase in government contracts. This phenomenon isn’t surprising, but the extent of it is.

“This was our first result: if you’re a state that has this random thing happen to you, you get a ton of government money,” Malloy said. “In the second part, we were trying to establish what’s the impact of that? What happens when you get a so-called helicopter drop of cash?”

This is the really intriguing part. There are certainly some local firms on the receiving end of these earmarks and contracts that directly benefit. But in looking at publicly traded companies in a state in the wake of these “spending shocks,” the researchers found on average that private-sector firms actually retrench. In the year after the rise of a new committee chairman, the average firm cuts back capital expenditures by about 15 percent. The average state also sees a $44 million annual drop in R&D spending by publicly traded companies.

This data comes from 232 instances of chairmanship changes over the past four decades, and the pattern holds for states large and small. The effect is particularly strong when unemployment is low and companies are operating near full capacity, when government projects may actually lure labor away from these firms and drive up the cost of business (as opposed to employing people who were out of work at the time).

“There are all sorts of theories about government money, that it could stimulate the economy, that it could crowd out local investment,” Malloy said. “We have evidence it’s crowding out investment.”

And this means powerful politicians may actually be bad for business back home.

This finding has implications for government spending outside of the context of states with mighty committee chairmen. But the authors aren’t endorsing the idea — which would surely resonate in the Republican primaries — that all government spending is harmful.

* — CORRECTION: Alaska was misidentified as Arkansas when this story was first published.

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.