Since the American housing crisis began five years ago, policymakers have devoted the bulk of their attention to the bubble’s most visible victims, homeowners who’ve lost their houses to foreclosure, or who look like they may any day now. This group has been the subject of congressional inquiries and legal settlements and numerous election-year speeches. Just this week, California’s attorney general has been pushing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to forgive some of the debt owed by underwater homeowners.

Considerably less attention has gone to a population deeply impacted by the housing collapse, perhaps because they likely never owned a house in the first place. These are the most extreme low-income households who’ve always rented – and who are today squeezed by the fact that everyone else now wants to rent, too.

As more people have left their homes (or are afraid to buy new ones), rental occupancy rates are skyrocketing across the country. Rents are going up everywhere as housing prices stagnate. And this effectively means the supply of affordable rental housing is shrinking exactly when the number of families in need of it is growing.

Miller-McCune’s Washington correspondent Emily Badger follows the ideas informing, explaining and influencing government, from the local think tank circuit to academic research that shapes D.C. policy from afar.

“This is really the result of the housing boom and bust that caused the recession, so these things are kind of happening simultaneously,” said Megan Bolton, a senior research analyst at the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “In the past, when you’ve had high poverty or high unemployment, you’ve often also had declining prices across the board in the entire housing market.”

Right now, though, that’s not the case, since the current recession was caused by a housing bubble. At other moments in the economy’s history, poverty has been high while rents have been low. Or rents have been high while poverty was low. But because rising poverty and rising rental rates are converging, the crisis of affordable housing is particularly acute.

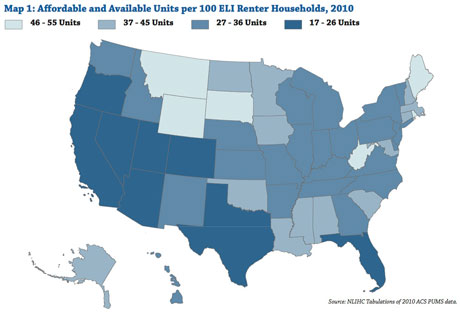

Bolton conducted a state-by-state analysis and found that the states with the least available affordable housing for extremely low-income families are also some of the states hit hardest by foreclosure, including Florida, Nevada, and California. This correlation hints at the connection between the original housing bubble and its impact on people who were never homeowners to start with.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development recognizes a category of households that are “extremely low income,” those that make less than 30 percent of the median family income in a metropolitan area. Across the country, 9.8 million households currently meet this definition – 200,000 more than did in 2009 – out of a renter population of about 40 million households.

Among the extremely low-income group, Bolton has found, for every 100 renter households, there are only 30 affordable and available units in the housing market. These are units that either currently house extremely low-income families, or that are vacant and available to them. Those other 70 extremely low-income households, Bolton said, are likely living in homes they can’t afford.

These families (and the “very low-income” ones just above them) have in part been bumped out of affordable housing by higher-income households taking up many of these rentals.

“People are wanting to try to find really good deals on whatever they can,” Bolton said. “If they can find an apartment that’s really affordable to them, they’re going to take it. And they’re going to take it much more willingly than they would have a few years ago.”

All of this means that the housing struggles of middle-income families may contribute to a domino effect that pushes some of the most extremely low-income all the way into homelessness.

Bolton’s numbers reflect national averages calculated from the 2010 American Community Survey, not numbers specific to individual communities. And so the problem is probably worse than her data indicate.

“Especially when you’re looking at the national level,” she said, “a lot of those affordable units might be in Wyoming,” i.e. not where the greatest need is.

This week, the Federal Housing Finance Agency is moving forward with a long-discussed proposal to sell foreclosed homes to bulk buyers who agree to rent them. And this may be a start to alleviating the problem. But Bolton also points to the need for a national housing trust fund to create and preserve affordable housing for the most distressed households. Such a trust was created in concept in 2008 under the Bush administration — but it has never been funded.

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.