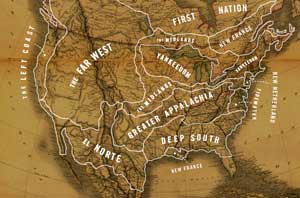

Colin Woodard suggests that we’ve been vastly oversimplifying things by talking about America’s internal divisions between red states and blue states, between “the coasts” and the “heartland,” between the urban and the rural or even the North, South, Midwest and West. Instead, the veteran journalist slices North America (sans Mexico from Tampico south) into eleven culturally distinct regions that look something like a continentally gerrymandered map gone wild.

Until more Americans grasp what this map implies, he believes, we’ll continue to have a hard time forging national consensus.

Woodard floats this thesis in a new book, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, that offers novel perspective on the current U.S. predicament of culture wars mixed with political paralysis mixed with economic disarray. His assessment recalls another region with complicated geography: the Balkans.

Woodard studied Eastern European history in college, and he spent the early years of his journalism career reporting from that part of the world, where centuries-old cultural fissures and historic events have left a deep mark on the present — and where those fault lines don’t overlay very neatly with national borders on a map.

“In returning to America and living in other parts of the country,” Woodard said this week, “it seemed clear to me these fissures exist on our continent as well. We just don’t recognize them.”

This idea has been broached before. Joel Garreau identified The Nine Nations of North America in his 1981 portrait of the country’s economic and cultural divisions. And historian David Hackett Fischer proposed later that decade, in Albion’s Seed, that four distinct British migrations had grafted parallel societies onto colonial soil.

But Woodard marries historical record with present-day observation into what he jokingly calls a “grand unified theory,” tracing the evolution of early settlement patterns through the regional differences that prompted the Civil War, the civil rights movement and current political polarization.

His theory rests on the idea that there has been tremendous continuity in regional cultures from the colonial era to the new millennium. He draws on literature arguing that the first self-sustaining settlement group to arrive in an empty territory (or, in the case of much of the U.S., a territory that’s been cleared of its existing inhabitants) has a dominating influence on the future evolution of that society and culture. The theory holds even when original settlers are far outnumbered by all of the people to come.

New York is a prime example. A global trading and financial center that prizes diversity and tolerance, to this day it shares many similarities with Amsterdam of 300 years ago. Dutch descendants, however, make up a fraction of 1 percent of the local population today.

These initial groups essentially laid down the cultural DNA that the rest of us who’ve come since have had to live to with,” Woodard said. “They created the institutions and cultural assumptions and norms over pieces of geography that formed the dominant culture that future groups encountered.”

Miller-McCune’s Washington correspondent Emily Badger follows the ideas informing, explaining and influencing government, from the local think tank circuit to academic research that shapes D.C. policy from afar.

(As a side note, this suggests that people who fear that the character of their communities will change dramatically with the influx of 21st century immigrants vastly overstate that threat.)

Among Woodard’s other “nations,” are “Yankeedom,” where Calvinist roots still feed public faith in the ability of government to do good; the originally Quaker and politically moderate “Midlands”; the deeply traditional and conservative “Tidewater,” settled by English gentry; and the individualistic “Greater Appalachia.” Woodard’s regions defy state boundaries. He groups Chicago with its northern neighbors and southern Illinois as part of Appalachia. California spans three nations: the “Left Coast,” the “Far West” and Spanish-influenced “El Norte.”

Of course, if these regions are defined today by the same fundamental cultural differences that divided them before the U.S. Revolution, that leads to the really unsettling proposition in Woodard’s book — that “shared American values” don’t really exist.

“Some people will find the notion that we don’t have a shared founding story and shared values and a shared model in society going back to the beginning … upsetting or even threatening,” Woodard said. “But it is in fact the case.”

Americans may look back to, say, the values of the founding fathers in 1776, or talk vaguely about “freedom” and “liberty.” “The problem is all of those traditional ideas and visions, those original intentions are true, but they’re only true for certain regional cultures,” Woodard said. “And they contradict each other. They can’t all be true of the same place as fundamental models.”

These divisions may also be widening. If his map is overlaid on top of Bill Bishop’s thesis in The Big Sort, Woodard says it looks as if Americans are not only sorting themselves into likeminded communities, but also likeminded nations, a trend that may only make consensus more elusive. Woodard doesn’t offer a prescription for reconciling all these nations, but he thinks we can’t have productive national policy discussions until we recognize that they exist (and surely election strategists will be the first ones to do this).

“Since many of these fundamental values and ideas of how society should be modeled are not compatible, there’s no way that you can just devise a compromise where everybody’s going to be happy,” Woodard said. “But maybe we can devise compromise where everybody’s grumbly but can live with it.”

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.