It is telling that the Creation Museum in Petersburg, Ky., wants the design of a biblical theme park that will showcase a 500-foot-long replica of Noah’s Ark to qualify for certification by the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design program, an industry standard for sustainable buildings.

Mike Zovath, senior vice president of Answers in Genesis, the “apologetics (i.e., Christianity-defending) ministry” that built the museum, is a climate change skeptic who toldThe Washington Post that he liked the idea of energy efficiency: “There is a pretty significant return on investment,” he said.

Whatever the motive, even conservative religious groups, historically far from the environmental forefront, are embracing the tenets of green building — or at least those promulgated by the U.S. Green Building Council, the member-based nonprofit that runs the program commonly known as LEED. A marketer’s dream come true, the program, which features a multifaceted approach to construction, is the most recognized name in green building in the country.

But one Doubting Thomas is effectively disparaging the program’s phenomenal success.

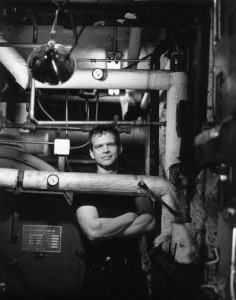

Henry Gifford has made his living designing mechanical systems for energy-efficient buildings in New York City. And he admits the program has popularized the idea of green building: “LEED has probably contributed more to the current popularity of green buildings in the public’s eye than anything else. It is such a valuable selling point that it is featured prominently in advertisements for buildings that achieve it. LEED-certified buildings make headlines, attract tenants and command higher prices.”

But for years, Gifford has been a tenacious and vocal opponent of LEED, claiming that the program’s “big return on investment” is more a matter of faith than fact, and that LEED simply “fills the need for a big lie to the public.” Last October, Gifford filed a class-action lawsuit for more than $100 million against the USGBC, accusing the nonprofit of making false claims about how much energy LEED-certified buildings actually save and using its claims to advance a monopoly in the market that robs legitimate experts — such as himself — of jobs.

In February, the complaint was amended and restructured as a conventional civil suit, with Gifford and three other plaintiffs seeking injunctive relief and monetary damages for lost sales and profits and related harm. While dropping the antitrust claims, among others, in the initial complaint, the plaintiffs continue to allege that the council has engaged in false advertising and deceptive practices.

While the council wouldn’t comment on ongoing litigation, in April it filed a motion for dismissal, accompanied by a 29-page memorandum arguing that the plaintiffs lack standing and have failed to state a claim upon which relief could be granted. While acknowledging that Gifford — described in the memorandum as “a longtime gadfly, preoccupied with critiquing USGBC and LEED through the media, internet forums and the like” — has the right to voice his criticisms to his heart’s content, the council argues he doesn’t have a case.

Gadfly or not, many green building industry experts would agree that Gifford is shedding light on a crucial issue. Other critics have pointed out examples of sporadic energy performance shortfalls with LEED buildings in the past. Gifford has thrown down a gauntlet which, in conjunction with other forces, is likely to influence the future course of energy conservation.

Green building, as we know it today, began taking shape in the 1990s, as public concern over climate change and waning fossil fuels led to a concerted effort to find and address the culprits — and that ultimately fingered the built environment. Architecture 2030, a nonprofit committed to environmental sustainability, used data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration to conclude that the building sector was responsible for 46.9 percent of carbon dioxide emissions in the U.S. in 2009, almost half again as much as the 33.5 percent generated by transportation sources, such as cars, that are usually spotlighted.

The building sector consumes 49 percent of all energy produced in the United States, and 77 percent of all the electricity produced in the nation is used to operate buildings. Experts believe those figures are similar in industrial countries worldwide.

Inspired by another green building program in the United Kingdom, the Green Building Council devised its own and officially launched LEED in 2000. Crafted to measure a building’s “greenness,” the program features a point system to score a checklist of considerations in various categories, from sustainable site development to materials selection to energy efficiency. Those seeking certification pay a registration fee and, if approved, a certification fee based on square footage. After review of requisite documentation, certification may be awarded at one of four levels: certified, silver, gold and, the most coveted, platinum.

Today, nearly 8,000 commercial projects covering a billion square feet are certified, and nearly 32,000 other commercial projects with more than 6 billion square feet are registered. On the residential side, more than 9,000 homes are certified and more than 40,000 others are registered. Also, more than 150,000 individuals from various building-related fields have become LEED Accredited Professionals, a credential that demonstrates program expertise.

“The LEED system has changed the market for environmentally friendly buildings in the U.S.,” Gifford says. “But there is an enormous problem: The best data available show that on average, they use more energy than comparable buildings. What has been created is the image of energy-efficient buildings, but not actual energy efficiency.”

Gifford’s contentions rely heavily on data from a 2008 National Buildings Institute study, partly funded by the Green Building Council, to examine energy performance of LEED-certified commercial buildings. Currently the most comprehensive public body of data on the subject, the study analyzed energy use of certified buildings and compared that with average energy use of commercial buildings as reported by the Energy Department.

“On average,” the study concluded, “LEED buildings are 25 to 30 percent more efficient than non-LEED buildings.”

Using the study’s data but not its analysis, Gifford released his own report, claiming that when interpreted accurately, the data show LEED-rated buildings actually use 29 percent more energy.

At the time, 552 buildings had been LEED-certified, and the study examined data from 121. Gifford says the initial problem is that numbers were reported only from willing building operators. It’s “a little like making generalizations about drivers’ blood alcohol levels from the results of people who volunteer for a roadside Breathalyzer test,” he wrote.

Gifford offers other critical analyses. For one, the study compares LEED buildings with the Energy Department’s data set for all existing buildings, when, he says, they should have been compared to data for (presumably more efficient) new buildings only.

But this complaint may be off-base. “Buildings older than 1960 are typically more efficient than newer buildings,” says Tristan Roberts, editorial director for the independent industry news source BuildingGreen.com. “So if anything, comparing LEED buildings against the whole data set may be a more rigorous comparison”

Indeed, before electricity became cheap and plentiful, buildings were relatively efficient because they often included features such as thick masonry walls and simpler mechanical systems. Plus, tenants and building owners now increasingly fill structures with electric devices such as home electronics, computers and security systems.

Oberlin College physicist John Scofield, for one, believes that the heavy reliance on cheap electricity among building professionals helps account for the increased energy usage by new buildings. “The owner and architect delude themselves into believing that one day electricity will be green,” he says. The reality, of course, is that electric energy from the grid is dirty.”

Originally drawn to the issue by Gifford’s report, Scofield examined the National Building Institute study and presented his own findings critical of LEED’s claims at the 2009 International Energy Program Evaluation Conference.

“There is no justification for claims that LEED-certified commercial buildings are using significantly less electricity or have significantly lower greenhouse-gas emissions associated with their operations than do conventional buildings,” he says. “LEED buildings do not save energy.”

His conclusion is based on how LEED buildings measure efficiency by using “site energy” and not “source energy.”

Measured at the building, site energy is the amount of heat and electricity represented in utility bills. It does not, however, account for the conversion of primary energy sources into electricity, which delivers more than half of the energy consumed by typical buildings. Generation of electricity elsewhere and transmitting it to a building is quite inefficient; three BTUs of energy are required to produce one BTU of electricity. Source energy measurement therefore more accurately reflects the true on- and off-site energy costs for a particular building.

“That’s why the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star program, for one, has proven to be a much better guideline, because it uses source energy as a metric for scoring buildings,” Scofield says. Energy Star was established in the early 1990s to help power plants reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, and has become an international standard for products ranging from computers and appliances to entire buildings.

Scofield also notes that, in the study, no correlation was found between the number of program points awarded in LEED’s category for energy efficiency and actual measured energy reduction. “The problem here is that LEED scores are based on projected energy use — calculated before construction begins,” he says. “In contrast, Energy Star scores are based entirely on measured source-energy consumption.”

The Green Building Council has been addressing some of these criticisms since before Gifford’s suit. Since 2009, it has required all certified buildings to provide performance data to track predicted savings against actual savings. In 2008, in a program for existing buildings, LEED required the applicant to report and monitor energy consumption for at least a year prior to certification.

Regardless, how the council faces another challenge will likely be relevant to the plaintiffs. As many local governments clamor to embrace sustainable building, the group has been working with industry organizations to translate LEED into standardized, optional, code-friendly language that municipalities can readily adopt. Paradoxically, widespread standardization of LEED certification may help competitors appeal to consumers who want more than what their codes prescribe.

“As these practices become standardized, how much will the general population care about green ‘plus,’ since LEED certification has a perceived prohibitive cost?” asks Shari Shapiro, an attorney who serves on the council’s legal advisory board. “If done well, LEED will evolve into something new.”

The rating program is being reinvented; the council expects to release a new version of the program in November 2012. An initial public comment period that began last November generated more than 5,000 remarks; another comment period is expected to begin this July.

“There is certainly part of me that is pleased the industry is restless,” says Brendan Owens, the council’s vice president of LEED technical development. “What I think is unproductive is to paint with too broad a brush. If you don’t like one thing about LEED, it’s not a reason to dismiss everything about it.”

Many LEED supporters point out that energy efficiency is not the only facet of the program, nor of the green building movement it helped galvanize. Water conservation, green materials and proximity to mass transit are among other major considerations of the LEED’s holistic approach.

Still, if energy performance continues to be an Achilles’ heel for LEED, other more energy-focused green options exist, such as Energy Star, which Scofield endorses.

Gifford himself is designing a system for 803 Knickerbocker in Brooklyn — what’s expected to be the first new apartment building in the U.S. to conform to the Passivhaus standard, an import from Germany that emphasizes insulation.

Ironically, Gifford’s lawsuit — like the interest in LEED by the Creation Museum — may be a measure of the program’s success. “Coca-Cola gets sued all the time,” Shapiro says. “Why? Because they’re Coca-Cola. A suit against the USGBC marks the arrival of green building.”

Others, like Edward Mazria, founder of Architecture 2030, see the suit as indicative of a rapidly evolving industry: “When you have tremendous activity, you also have tremendous scrutiny.”

Mazria’s organization issued the 2030 Challenge, asking building professionals, governments and industry to reduce fossil-fuel energy consumption by all types of buildings from 2003 levels by 60 percent by 2030. The program also sets increasingly tighter standards so that all new buildings and major renovations will be “carbon neutral” by 2030 as well. Almost all professional organizations, including the Green Building Council, the federal government and many cities and states, have taken up the challenge through resolutions, executive orders and legislation.

“Two major events — the meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan and the U.N. entering the confrontation in Libya — are examples of a larger perpetual drama playing out in order to meet voracious building-sector energy demand,” Mazria says. “The transformation away from this will stem from the architecture, engineering and planning community, which configures the entire built environment. We set the agenda — and that agenda is changing. Regardless of any contentious issues, the transformation of the building sector is under way.”

The real question, he suggests, isn’t which well-intentioned program does what: “The question is: Will it happen quickly enough to avert major global issues?”

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.