The rapid growth in the U.S. Hispanic population over the last 40 years — both in terms of raw numbers and percentage of the population — is probably the most important emergent force in American politics today. The evidence is around us: In 2008, each party conducted an entire presidential primary debate in Spanish. In 2009, the first Hispanic judge, Sonia Sotomayor, was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. And in 2010, for the first time ever in a single election, three Hispanic candidates won top statewide offices: Republican Brian Sandoval became Nevada’s first Hispanic governor; Republican Susana Martinez won in New Mexico to become the nation’s first Hispanic woman elected governor; and Republican Marco Rubio was elected to represent Florida in the U.S. Senate.

Despite these notable top-of-the-ticket wins by Hispanic Republicans in 2010, most political observers continue to assume there is significant and stable support for Democrats among Hispanics, similar to the support that African Americans have shown in recent decades. Indeed, new Hispanic voters have entered the electorate more often as Democrats than as Republicans in recent elections.

But the current degree of Hispanic attachment to the Democratic Party is by no means a future certainty.

We examined Hispanic turnout and partisanship in midterm elections — that is, the elections where turnout isn’t significantly affected by charismatic presidential candidates — from 1978 to 2006 by collecting and matching data from several sources. First, we combined more than 150 academic and high-quality commercial public opinion surveys, each of which employed a nationally representative sample of at least 1,000 respondents. In addition to this combined dataset, we added voter turnout data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, creating what we believe is the most comprehensive demographic and voting behavior dataset ever compiled for midterm elections. The data allowed us to examine both overall trends and individual behavior. (Individual level data is not yet publicly available for the 2010 midterm election, but aggregate results are considered here.)

On the surface, the information we gathered supports some common political wisdom: A vast buildup of potential Hispanic voters, primarily composed of immigrant citizens and young U.S.-born Hispanics, has generally tended to favor Democrats but turned out to vote at far lower levels than whites or African Americans during the last three decades.

Our dataset, however, shows that the common wisdom misses a potentially momentous prospect.

Once we accounted for demographic differences known to affect turnout, we found that Hispanics actually vote at rates very similar to those of whites and blacks. In other words, much of the explanation for the low turnout rates for Hispanics is not related to being Hispanic but to Hispanics being younger and having less education on average than whites or blacks.

Similarly, we found that in terms of both party identification and the strength of that partisanship, the differences between whites and Hispanics disappears when individual-level characteristics such as age and education are taken into account. In short, the data suggest that Hispanics have not been genuinely incorporated into the party system or made anything like a deep commitment to either party.

But that incorporation and commitment may come soon.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

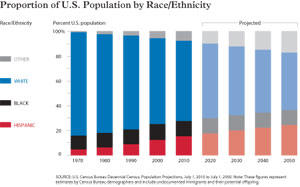

Proportion of U.S. Population by Race/Ethnicity

The large influx of Hispanic immigrants into the United States over the past four and a half decades resembles — in terms of magnitude and proportion — the great immigration wave from southern and eastern Europe that took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like today’s Hispanic population, a large body of research shows, these earlier immigrants possessed limited experience with U.S. politics and received few partisan cues from their parents. The Democratic Party captured these voters because the party supported policies that addressed their central concern — the economic turmoil of the Great Depression — while the GOP took a hands-off approach. The resulting Democratic affiliation reorganized American politics for the next 30 years.

Vote-eligible Hispanic immigrants and their U.S.-born children today appear to have a similar lack of political experience and affiliation. In a partisan sense, they are legitimately up for grabs — and consequently sit in a strategic and increasingly important position in American politics.

As their average education level, income, age and familiarity with the political process increase over time, Hispanics can be expected to enter the active electorate in far higher numbers than they have to date. Current conditions — the worst economic dislocation since the Great Depression combined with fierce controversy over an issue of central concern to Hispanics, immigration — provide the salient issues that could move Hispanics to connect deeply with one party or the other. The party that best handles those issues of high importance to Hispanics, our research strongly suggests, could be the beneficiary of a shift in turnout and partisan attachment that alters the balance of political power in America not just for the next presidential or midterm election but for decades.

Because Hispanic allegiance to both parties is weak, the question remains: What can Republicans or Democrats do to seal the Hispanic political deal?

In 1966, the U.S. population was estimated at 200 million, with only about 8.5 million individuals, or 4 percent, being of Hispanic descent. Forty years later, the population has grown by 100 million persons. Hispanic immigrants and their U.S.-born offspring accounted for 29 million of those people; an estimated 15 million children born in America to undocumented Hispanic parents during this time bring the total of eligible Hispanic voters added since 1966 to as many as 45 million.

Demographers project that the share of the population identifying as Hispanic will continue to increase for decades to come. The Hispanic population, now about 15 percent of the U.S. population, is expected to grow to as much as 25 percent of the total population by 2050. In contrast, blacks are projected to remain constant at approximately 12 percent of the population, while whites are expected to fall below 50 percent.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

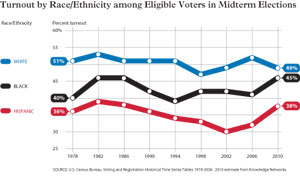

Turnout by Race/Ethnicity among Eligible Voters in Midterm Elections

Despite the rapid growth of the Hispanic population, the percentage of Hispanics who vote in midterm elections is very low compared to whites and blacks. On average, about half of eligible whites vote in midterms, and just over 40 percent of eligible blacks vote in the same elections. The proportion of Hispanics who enter the voting booth reached a high of 39 percent in 1982 and has declined steadily since then to just over 30 percent in 2006. By 2006, the turnout difference between Hispanics and whites had grown to around 20 percent. The portion of Hispanics voting in 2010 — a year with significant attention around immigration — increased to around 38 percent.

These aggregate differences in turnout are clearly large enough to have meaning for election outcomes. For example, if Hispanics had voted at the same rate as whites in 1978, an additional 665,000 votes would have been cast in that election, representing approximately a 1 percent increase in the total vote. Because of the growth in the number of eligible Hispanic voters, and the decline in participation over 32 years, the Hispanic turnout deficit swelled to represent some 3.3 million votes (or about 3.5 percent of the total cast) in 2006.

Many an election is decided by less than 3 percentage points.

Of course, Hispanics as a group are different from whites and blacks in more ways than just ethnicity. A variety of research shows that Hispanic immigrants and their descendants tend to be younger and less educated, to face language barriers and, often, to possess fewer resources that facilitate participation in U.S. politics. Such individual characteristics have repeatedly been shown to have powerful effects on voting. But the specific question remained: If Hispanics had the same demographic characteristics as whites and blacks, would their turnout rate increase?

Using individual-level data from our dataset, we found that Hispanics turned out at similar rates to whites and blacks once we accounted for demographic differences between the groups that are known to affect turnout (that is, age, gender, work status, education). In six of the eight midterm elections in our study, the rates of turnout for Hispanics and whites were not statistically different, once the demographic differences were accounted for. Only in 1982 did Hispanics vote at lower rates than whites, and in 1994, Hispanics voted at higher rates than whites once other demographic differences were analyzed.

These results suggest that much of the explanation for the lower aggregate rates of turnout for Hispanics compared to whites and blacks is not related to being Hispanic but rather to Hispanics being younger and having less education on average than whites or blacks.

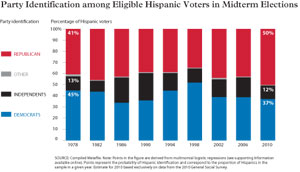

In the aggregate, Democrats maintained about a 20 to 25 percent advantage in party identification among Hispanics in midterm elections between 1978 and 2010. This gap would appear to provide a clear mobilization advantage for Democratic candidates, akin to what is seen among blacks.

As with to voter turnout, however, we turned our attention to individual-level analyses that allowed us to account for demographic differences between Hispanics, whites and blacks in regard to party identification. Compared to whites, blacks were found to be less likely to be Republican and more likely to be Democratic across most elections years, a result to be expected given the long line of research supporting it.

But by and large, Hispanics did not follow the same pattern. The results we found suggest that once individual-level characteristics such as age and education are considered, differences between whites and Hispanics in terms of both party identification and the strength of partisan attachment disappear. That’s to say, as with whites, there are partisan swings in the Hispanic community and only a modest attachment to parties, suggesting that Hispanics have not been fully incorporated into the party system.

We have presented the first multi-decade, time-series examination of political engagement and party attachment among ethnic populations in the U.S. Through the data, we found that dramatic growth in the Hispanic population since the 1970s did not correspond with an increase in either turnout or the strengthening of attachment to a major political party. On the contrary, aggregate trends revealed a general decline in Hispanic voter turnout and only a fragile commitment to Democrats or Republicans since the early 1980s.

But beneath those aggregate trends, the data tell another story — of a mass migration to America that is similar to an earlier migration, and of the huge political potential of a Hispanic electorate poised to become far more politically active than it has been. As with circumstances underlying previous electoral transformations, the current social, economic and political climate confronting vulnerable Americans has the potential to jolt complacent Hispanics into political action.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Party Identification among Eligible Hispanic Voters in Midterm Elections

How the immigration issue is resolved and how undocumented immigrants are treated in what could be a long-term economic downturn, are precisely the kind of crosscutting, highly salient issues from which — a long line of political science research shows — strong and long-lasting party ties are made.

When a country has more than 6.6 million families with a head of household and/or spouse who migrated without authorization, immigration policy is, as a matter of factual reality, as much about keeping families together as it is about border control. Many in the Republican Party repudiated the comprehensive immigration reform measures championed by President George W. Bush during his term in office and have instead adopted a strong stance against undocumented immigrants, most notable of which was Arizona’s SB 1070, a law that, among its many controversial facets, requires individuals to prove legal residence in the U.S. on the request of local and state authorities.

Such policies make the Hispanic community wary of the GOP for now. And given the recent ascendance of hard-line, anti-immigration factions within the party, a shift to more immigrant-friendly positions is by no means clear. But the emergence of high-profile Hispanic Republicans in positions of real political prominence could well steer the GOP back toward Bush-style immigration reform and help make Hispanics comfortable with the Republican Party again.

Whether Democrats can connect, strongly and long-term, with the Hispanic community through labor and economic policies — and thus become the majority party for decades — also remains far from certain. There is much anecdotal evidence on political competition and friction among blacks and Hispanics, particularly at state and local levels. Studies of black and Hispanic attitudes often raise doubts about the potential for what might otherwise seem like a natural black-Hispanic coalition, and there is little to suggest that black or Hispanic leaders are eager to share party resources or civic positions in the near future.

Issues surrounding competition for jobs are often associated with political pressure for increased immigration control and enforcement, particularly with regard to securing the southern border and detaining undocumented workers. Such issues are likely to put tremendous pressure on the existing Democratic coalition.

What we know is that by their sheer numbers and their potential for political acculturation, Hispanics are poised to transform our party system for decades, if not generations, to come. The significant questions remaining are when, and to the benefit of which party, the transformation occurs.

A longer account of this study, including an extensive discussion of the data obtained and methodology used, is available at the Stanford Institute for the Quantitative Study of Society website at www.siqss.com/.

(Stanford doctoral candidates Curtiss L. Cobb III, Ali A. Valenzuela and Wendy T. Gross also contributed to this article)