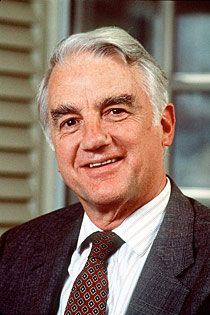

A longtime critic of higher education, Derek Bok is the author of six books on the ivory tower, most recently Our Underachieving Colleges: A Candid Look at How Much Students Learn and Why They Should Be Learning More, published in 2005. Bok has an insider’s view: He was president of Harvard from 1971 to 1991 and acting president from 2006 to 2007, the only person to serve twice in the job.

During his first stint, Bok established what is now the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning to help boost the quality of instruction at Harvard. Today, at 80, he is a research professor at the Harvard Kennedy School. His latest book, The Politics of Happiness: What Government Can Learn from the New Research on Well-Being, was published last year. Bok spoke recently to Miller-McCune about his hopes for undergraduate education in America.

Miller-McCune: Professor Bok, you’ve written that teaching students to think critically is the principal mission of a university. What do you make of the fact that college students today study half as much as they did 50 years ago?

Derek Bok: I think you have a lot of students out there who look upon college as a way of getting a necessary credential in order to get a good job. So, they take vocational courses, and they don’t put a great deal of effort into them. They don’t really see the importance of studying hard. That could be hard for professors to deal with. Sometimes you end up saying, “Oh heck, if they’re not going to do the homework, I just can’t assign as much, because it doesn’t do any good.” So you get into this kind of tacit agreement: The students don’t make trouble, and the professors don’t demand enough work.

M-M: Are professors too preoccupied with research to pay much attention to undergraduates?

DB: I don’t think you can put the blame too easily on research, even though I know it’s popular to do so. The authors [of Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses] found that the highly selective colleges were the ones where the most learning went on. The selective colleges are also the ones where most of the research goes on. Also, faculty surveys show that even in research universities, professors spend twice as much time on their teaching as they do on their research. The great majority of American professors — about 75 percent — say they’re more interested in teaching.

M-M: How do you explain the poor performance of so many college students on tests of critical thinking and complex reasoning?

DB: Colleges are in a kind of competition with some extremely smart people who are working very hard to capture the time and attention of undergraduates. I’m referring to the people who make iPhones, television sets, computer games, Internet, Facebook — a whole set of things that are designed to soak up the time. Meanwhile, colleges go on doing very much the same thing they’ve been doing forever and ever.

There’s a problem there, but I don’t think it’s that professors are involved in their research. Faculties have to recognize that this problem exists and that different kinds of teaching are going to be required — not just spending more time preparing your lectures in the same old way but really different kinds of teaching that are more likely to challenge and motivate students in the classroom.

M-M: College students have always had social distractions.

DB: Quite true, and they’ve always been quite potent, but not in the volume and not with the sophistication that they exist today. I think they’re becoming more numerous and more effective.

M-M: When you were a professor, how did you engage your students?

DB: Well, I had a completely different orientation because I taught in Harvard Law School. In the late 19th century, Harvard Law School invented the whole idea of Socratic teaching so that we didn’t lecture at all; it was all making students think. And that’s one reason I believe in it so strongly, because it just transformed my way of thinking about problems. I’ve been feeding off it ever since, not just in my brief career in law or as a law teacher but in academic administration. It’s the same kind of thinking clearly about human situations and taking account of arguments on both sides and figuring out what evidence is relevant and how to get it. Those are universal skills, and they were drilled into me as a student, and I carried it over into my teaching, as we all did.

M-M: What changes did you make to promote undergraduate learning when you were president of Harvard?

DB: We revised the undergraduate curriculum the first time I was president, and we revised it again when I came in for a year to keep things going between Larry Summers and the current president, Drew Faust. Both times, we completely revamped the curriculum to make it more interesting and effective. When you change a curriculum completely and have all the faculty debates that go into that, you not only create a new structure that you hope will be better than what it replaced, you also focus the faculty’s attention and get them involved in the structure and the meaning and the purpose of undergraduate education. And so you release a lot of new energy and a lot of new courses get created and a lot of senior professors get more involved. That’s why you need to change your curriculum every generation.

Also, we introduced student evaluations, which are very old hat now. We introduced a certain amount of assessment, including the [Collegiate Learning Assessment] test. We took surveys of how students had improved in their writing. You have to keep doing a lot of things. We’ve been hampered in the past by the fact that we didn’t have very good instruments for measuring student progress. You can innovate all you want, but if you don’t have a good yardstick to measure whether your innovations are actually producing improvements in student learning, it’s hard to get very far. Even the CLA test that these authors use has some very significant problems in terms of its validity.

M-M: The CLA is a test of undergraduate writing and reasoning ability used on a voluntary basis by only 219 colleges, a fraction of the more than 5,000 colleges in the United States. In the past, you’ve spoken out against a federal mandate for standardized tests of college learning, a proposal that was under consideration during the administration of former President George W. Bush.

DB: If the government tried to do to colleges what they have done to K-12 schools, it would really be quite disastrous. We don’t have adequate tools for it; it wouldn’t work the way they think it will work, and it would tend to have a dampening effect on the search for better measures, because the ones that were mandated would tend to get frozen in place. In the public schools, they’ve done studies showing that the effect of the standardized tests is to take time away from physical training and exercise, to take time away from music and arts, to take time away from civics. Those are all losses. We shouldn’t get so hung up on the workplace skills of critical thinking and communication that we neglect the other aspects of college, which are important to helping prepare students to live a full life.

M-M: What about attaching conditions to federal financial aid to universities in order to encourage more investment in undergraduate education, as some reformers suggest? What about raising the taxes on the investments of wealthy institutions if they fail to make undergraduate education a priority?

DB: [Laughs] You’re going to get the federal government deciding what proper investment in education is? We’ve never gotten into that. I don’t think the federal government wants to get into it. I don’t think they’d be very good at it. I think it would result in standardized, one-size-fits-all solutions, which would cut against one of the great advantages of our system, compared to that of other countries, which is that our system has a lot of variety and experimentation and different approaches. The moment you start saying we’re going to condition financial aid, on which every college in the United States depends, on living up to a set of standardized indicators promulgated by the federal government, you have taken a big bite out of the kind of diversity and complexity of American higher education. That would be a very great error indeed.

M-M: When you stepped down as president of Harvard in 1991, you said that the moral development of students was being neglected in the rush to obtain scientific knowledge. What did you mean?

DB: Moral education, and reasoning about ethical problems and trying to build character in the students, used to be a much more prominent part of undergraduate education. Back in the time of the ancient Greeks, it was the most important aim of higher education. At the end of the 19th century, it began to go into eclipse, because we began to become enamored of something that is usually called positivism, in the sense that real scholars should not deal with questions of value but rather should concentrate on getting determinative answers based on data and logic. And that kind of put moral education into an eclipse. In colleges as a whole, these courses went out of fashion. They’ve come back somewhat more recently, as everyone has become more interested in ethical issues like abortion and stem cells. But they still are not required on a great many campuses. In my opinion, not only in college but very much in professional schools as well, we have some work to do in giving moral education the place that it deserves as part of a well-rounded education.

M-M: Are you optimistic about the possibility of university reform?

DB: Yes, and that’s a bit recent. I was quite pessimistic in Our Underachieving Colleges, but I have been looking closely at the problem ever since. Better methods, more active methods of teaching have clearly been slowly but steadily increasing. The one thing people are kind of united on is that if you really think critical-thinking and problem-solving and higher-order reasoning skills are important, what you don’t want to do is just get up there and give lectures. That’s a passive form of education that’s not very good at teaching people how to think clearly or communicate clearly.

Accrediting organizations are putting a lot of pressure on institutions to rethink their methods and get into the business of assessing. When you start to assess, you become aware of the things that these authors bring out in their books: The students aren’t learning as much as you thought they were. That is a powerful motivation to colleges to look for more effective methods of instruction. I see that happening now to a much greater extent than I did five years ago. So, my own guess would be that if we don’t muck it up, if we try to encourage it and we don’t try to stifle it by imposing some omnibus solution from above, we’re going to make a lot of progress.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.