Glacier National Park in Montana, one of the 10 oldest parks in the United States, is celebrating its centennial this year, but its glaciers won’t be around for another 100 years: They will melt away by 2030, if not sooner, because of global warming.

In California, Joshua Tree National Park is preparing to celebrate its 75th anniversary in 2011, but the trees themselves, iconic symbols and “life centers” of the Mojave Desert, are projected to die out this century. Joshua trees need winter freezes to flower and produce seed, and the Mojave is heating up.

Other parks, including Virginia’s Historic Jamestowne, where the colonial history of the U.S. began in 1607, could be washed away before the century’s end in temperatures approaching those of tropical Panama City, Much of Florida’s Everglades could be underwater, too.

In a strategic plan released this month, National Park Service Director Jon Jarvis calls climate change “the greatest threat to the integrity of our national parks that we have ever experienced.”

“We are unafraid to discuss the role of slavery in the Civil War or the imprisonment of American citizens of Japanese ethnicity during WWII,” he said. “We should not be afraid to talk about climate change. … How will we choose, as the sea rises, which cultural sites we save? How do we decide that the next site for the giant sequoias is hundreds of miles north?”

National Parks Most At Peril

According to a late 2009 report from the Rocky Mountain Climate Organization and the NRDC, these are the 25 U.S. national parks facing the greatest and most immediate threat from climate change.

• Acadia National Park

• Assateague Island National Seashore

• Bandelier National Monument

• Biscayne National Park

• Cape Hatteras National Seashore

• Colonial National Historical Park

• Denali National Park and Preserve

• Dry Tortugas National Park

• Ellis Island National Monument

• Everglades National Park

• Glacier National Park

• Great Smoky Mountains National Park

• Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

• Joshua Tree National Park

• Lake Mead National Recreation Area

• Mesa Verde National Park

• Mount Rainier National Park

• Padre Island National Seashore

• Rocky Mountain National Park

• Saguaro National Park

• Theodore Roosevelt National Park

• Virgin Islands National Park/Virgin Islands

Coral Reef National Monument

• Yellowstone National Park

• Yosemite National Park

• Zion National Park

For the full report, click here.

The plan marks the first time that the Park Service has publicly committed to a head-on effort throughout its 84 million acres of scenic land, in collaboration with other federal land managers, to deal with the disruptions of climate change. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released a similar plan last year.

“Not facing up to climate change would be catastrophic for the future of the national parks,” said David Graber, chief scientist for the Park Service Pacific West Region, encompassing the West Coast and Pacific Islands. “It’s the first utterly essential step in a very long trip. We’re trying to buy time. We’re clearly looking for ways to provide the opportunity for species to exist for decades and centuries longer.”

The plan also signals that a sea change may be coming in the way the parks manage their resources, no longer by letting nature take its course, but rather by intervening to save species and ecosystems from oblivion. From now on, a top-level agency climate change coordinating group will address such tough policy questions as whether to help wild animals migrate to cooler areas and distribute plants and trees that can’t migrate on their own, what to do when one park’s native species becomes another park’s invasive species and how to handle ecosystems that have been reshuffled by drought and floods.

It will not be easy. Even among conservationists, Graber said, there are some who believe it is better to hope for the best and not meddle with nature — although, he said, he is not one of them.

“The National Park Service is a very conservative organization,” said Graber, who helped oversee the strategic plan as a member of the agency’s Climate Change Response Steering Committee. “One of our watchwords for the past half-century is, ‘Nature knows best, let nature do what it does.’ Moving from that to some kind of eco-engineering is a very difficult philosophical and psychological change. If the Park Service is going to embark on a really serious trajectory, it’s going to have to have a conversation with the American people.”

Ironically, the park plan comes during a summer in which Congress failed to act on legislation that would have put a cap on carbon dioxide, a heat-trapping greenhouse gas that triggers climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas have raised global temperatures by more than 1 degree Fahrenheit since 1900. According to U.S. government estimates, if no action is taken to curb these gases, global temperatures could rise by as much as 11.5 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of this century, and the sea level could rise by as much as 4 feet. Under that worst-case scenario, Dry Tortugas National Park — seven coral reef and sand islands less than 3 feet high, which serves as key resting stops for migrating birds, 70 miles off the coast of Florida — would likely be the first national park to be lost this century.

“Climate change is a huge, transforming, all-encompassing threat to the national parks,” said Stephen Saunders, founder and president of the Rocky Mountain Climate Organization, a nonprofit group that released a report with the Natural Resources Defense Council last year, naming Dry Tortugas, Jamestown, Glacier and Joshua Tree as four of the nation’s 25 most imperiled national parks.

“This is not just about melting polar icecaps,” Saunders said. “It’s about places close to home that we love. We have never lost entire national parks before.”

Saunders, who oversaw the Park Service as deputy assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior during the Clinton administration, said Jarvis’ statement alone would go far to galvanize the agency.

“When the director is that clear that this is the greatest challenge, then doors get opened for people to take action,” Saunders said. “In the past, I’ve been critical of the national parks for not doing enough. Politically, they’ve been shackled, and the shackles have been taken off. This is a very good job.”

Saunders’ group and the NRDC have called on Congress to designate brand-new parks and expand existing parks to help save America’s best lands from the ravages of climate change. They say the parks should be allowed to redirect a portion of their visitor fees to help cope with climate change.

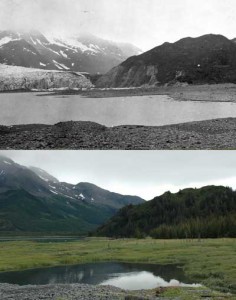

The parks are already changing as the Earth warms, and not for the better. Only 25 of the 150 glaciers that were present a century ago in Glacier National Park remain today, and they are shrinking. In New Mexico, Bandelier National Monument has lost 90 percent of its piñon forest to heat, drought and beetles. At Jamestown, Hurricane Isabel flooded 90 percent of the park’s 1 million cultural artifacts in 2003, and the entire collection had to be moved. At Saguaro National Park in Arizona, hotter, drier conditions favor an invasive grass that is crowding out the native saguaro cactus.

Some parks are already intervening to try to make species more resilient to climate change. Point Reyes National Seashore in California has removed two dams in a large estuary to help bring back endangered trout and salmon. Everglades National Park is removing canals and levees to restore natural freshwater flows and help keep saltwater out. And at Hawaii Volcanoes and Haleakala national parks, biologists are preparing to disperse 12,000 seeds and cuttings of 50 rare species of flowering plants to new locations: They hope to beat the odds of extinction in a shifting rainforest.

“Everything is being viewed as an experiment.” Graber said. “This is all unprecedented.”

The Park Service plan requires managers to draw up different scenarios for confronting the uncertainties ahead. In a trial run in 2007, scientists came up with a “summer soaker” scenario for Joshua Tree in which warmer temperatures and summer monsoons would likely wipe out the trees and bighorn sheep. Under a “dune” scenario, they said, drought and wildfire would destroy all the park’s vegetation.

For the Kaloko-Honokohau National Historic Park on Hawaii’s Big Island, scientists drew up a “sink or swim” scenario in which the park’s fishponds would be flooded, and a “water world” scenario in which everything, including the park’s petroglyphs and ancient burials, would be under water. In that case, they said, the park could become an “oceanic and climate change research learning center” to study the effects of sea level rise.

“This crisis is daunting,” the new Park Service plan says, “but national parks can provide redemption. For one of the most precious values of the national parks remains their ability to teach us about ourselves and how we relate to the natural world.”