In his long career, James Dehlsen has started and sold several green-energy companies and played an important role in making wind- and ocean-powered electrical generation commercially viable.

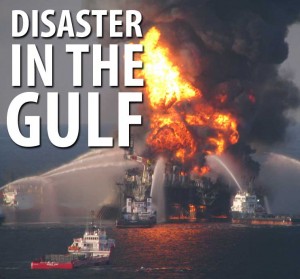

So when BP‘s Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig blew up in the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, it wasn’t long before Dehlsen started thinking about ways to cap a broken well that was spewing crude oil and gas 5,000 feet under water.

“It was very much driven by the enormity of the potential catastrophe and just trying to think about what might be different solutions,” says Dehlsen, CEO of Ecomerit Technologies, a Carpinteria, Calif., company.

BP lately has had some limited success with a cap that allows operators to siphon some of the escaping oil to ships on the surface. That came after weeks of failure, as BP unsuccessfully tried to use a 140-ton steel dome to stem the gushing oil, among other methods.

Dehlsen was looking for a more subtle approach — the “soft path” — to solving problems favored by alternative energy guru Amory Lovins.

“It just seemed like there might be another way you could approach it,” he says. “You gently coax the jet and plume [of oil] to go in the right direction, and you facilitate it getting to the surface. It’s something you could do relatively quickly and without needing to have a massive platform on the surface.”

Ecomerit engineers came up with the “thermal taming chamber,” a delicate-looking device that looks a little like a UFO. (For an animation, click here.) The system includes an ingenious design to prevent the formation of hydrates, the frozen natural gas crystals that fatally clogged the containment dome.

But while Dehlsen has been trying to interest BP and various U.S. government agencies in his solution, it seems like no one is listening.

“It seems to me it should have the potential for complete containment,” says Dehlsen, who has several patents pending on the idea. “I think the ability to just cut it off completely is high. I think that ought to be the priority.”

Max McGahan, a harried-sounding BP spokesman, said Monday that the company is reviewing more than 30,000 proposals — submitted through BP’s website — to help with the oil spill. The ideas range from well-sealing strategies to containment fixes that would keep the pollution from reaching pristine beaches.

“They’re all being looked at,” McGahan said, adding that he was not in a position to comment on the status of any particular proposal. Since the Deepwater Horizon blowout, observers have noted that little new deepwater containment technology has been advanced in the last quarter century since a spate of catastrophic blowouts in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a status quo that mirrors cleanup technology.

McGahan said BP has been collecting about 11,000 barrels of oil a day with its containment cap.

“We hope in the next few days we can improve that containment,” he said. The company still expects two relief wells that are currently being drilled will enable a definitive “bottom kill” of the leaking well sometime in August.

Were it to be deployed, Dehlsen’s thermal taming chamber might do the trick at a fraction of the cost — and with off-the-shelf technology.

Attached to thousands of feet of flexible insulated conduit, the bell-like containment chamber, with a sturdy, thin-waisted tube called a “venturi” hanging underneath, would be maneuvered into place with propellor-driven thrusters until its tripod feet reach the sea floor. The thrusters and remotely operated underwater vehicles — ROVs — would help maneuver the venturi over the well tube, funneling the escaping oil and gas into a single vertical plume.

“You essentially let that venturi settle and encircle the area of the discharge, and that’s the first step in ensuring you’ve got the potential for freezing under control,” he says

A large, heated “proboscis” descends from the underside of the containment dome into the open mouth of the venturi. As the massive electrically powered coil inside starts to heat, it forms a convection column that draws escaping gas and oil into the collection tube.

“Little by little, you start to organize a flow and a discharge plume going up into the top of the chamber and on up the conduit,” Dehlsen says. Finally, a surrounding retractable curtain drops to the sea floor, closing off the well from the surrounding environment.

Collection ships at the surface could, meanwhile, separate the oil, gas and seawater, with the gas being used to fire the generator powering the 5-megawatt heating coil, he says.

“This concept is something we started on four or five weeks ago,” Dehlsen says. “There’s still a lot of engineering that needs to go into something like this and getting the supply chains sorted out, and all of that.” He estimates construction could start within a month of getting a green light.

But before getting to that point, BP and the federal agencies involved in responding to the disaster would need to make a decision. And despite efforts that have included personally reaching out to Energy Department Secretary Steven Chu, Dehlsen has waited in vain for someone to respond.

“We’re targeting the Department of Interior, the Coast Guard, the Department of Energy and the executive office,” he says. “It could be in somebody’s in-basket — who knows? That’s one of those things that I think is a challenge: getting to the proper decision-makers.”

It isn’t as though Dehlsen is a fly-by-night backyard amateur inventor of the kind that have suggested schemes like setting off a small nuclear bomb to seal off the well or sinking a warship so that its hull comes to rest atop the leaking pipe.

In the 1970s Dehlsen developed Triflon (now called Tri-Flow), a fluid lubricant consisting of micron-sized Teflon particles that made machinery like bicycle chains run more efficiently. After selling the company he had founded in 1980, he started Zond, which developed major wind energy generation projects. General Electric wound up buying that company in 2002.

Dehlsen launched Ecomerit in the late 1990s as he became interested in harvesting energy from ocean currents and wave power. The company developed efficient new drivetrain technology that could handle very low RPM and high torque — and so got Dehlsen sidetracked into starting a new wind turbine company called Clipper Windpower.

Clipper is making giant wind turbines with 150-meter rotors capable generating 10 megawatts of electricity that will go up off the northeastern coast of England. “These machines over their lifetime are equivalent to about 1.9 million barrels of oil,” Dehlsen says. “That’s pretty much the scale of the largest supertankers.”

Nowadays, as he refocuses on Ecomerit and its ocean energy technologies, Dehlsen thinks that even if the thermal taming chamber is not used on this leaking well, it could become a state-of-the-art emergency kit in the event of another blowout.

The thermal chambers might even replace the offshore oil platforms that dot the gulf. Rather than having giant platforms, “you would go to a subsurface containment vessel,” he says. The devices, with their floating, slinky-like conduits, could collect oil from a well that would be offloaded by ships every couple of weeks.

“I think there’s the possibility that this could actually be the precursor to technology that would allow for a different way of harnessing the flow of a well,” he says.