Water in the desert is always a pleasant discovery, even if 20 carloads of people have beaten you there.

Location: 30 miles north-east of Ensenada, in Baja Norte.

Conditions: The sun continues to shine every day. Evening temperatures drop to the upper 50s.

Discussion: The clear skies and dry landscape of the Valle de Guadalupe made the talk of water seem so abstract and distant. Underground aquifers and rain? I see none. I needed the real thing: flowing water.

One of our hopes, while we were in the mountains of Baja, was to visit a hot spring — and we heard of one in the area. We asked around and got closer and closer, “Ah sí, las aguas termales, por aya!” It seemed like a nice detour, but I was skeptical whether we’d see any flowing water. Little did I know.

The dirt road went past a vineyard and led us into three river crossings — shallow water with sand, rocks, and all. We approached the first riverbed with hesitation, but after seeing a mid-sized sedan go barreling across the water, drenching its laughing occupants, we gained confidence. There was nothing to fear, as our silver van, el Hippo, was quite pleased with the under body wash.

The hot spring was in a ranch, which collected a $5 fee upon entry. The idea that this was a semi-secret destination turned out to be total fantasy, as we joined 20 or more cars parked haphazardly around the canyon – complete with a makeshift volleyball net, BBQs on pickup truck beds, and kids splashing water in the river. (Everyone suddenly left on Monday morning, just as we were getting used to the merry-making.) I was ecstatic. Here is the water, and indeed, it was flowing! But not as much as the surprise we found up stream: a big waterfall.

“After you’ve see one, you’ve seen them all.” Perhaps Ronald Reagan did say that about the redwood trees, or perhaps it’s a myth. I used to share that view in regards to waterfalls, especially in the wet tropics. But in an arid canyon, there is nothing like it, gushing alongside sheer red cliffs, with springtime blossoms of succulents clinging to the vertical walls. This was water — threading through a hostile territory, bringing life to oaks and sycamores that would otherwise not exist.

Finally, we made it to the hot spring. There is no better way to watch stars than from a tub of warm muddy water. The hot springs were fully worth the effort, but they were even better due to the unforeseen surprises we found along the way. The capstone came when I visited Frederico, the old man who owns the ranch; I wanted to interview him about the river.

After he slowly took a seat in the patio, I asked Frederico about water. Instead of discussing the river, he replied with unexpected strength: “You know, the Aztecs lived on an island surrounded by lakes in the Valley of Mexico, where Mexico City is now,” he told me. “Now the whole valley is nearly dry. What does that tell you? Also, it is a lie that Spaniards conquered the Aztecs – it was their diseases.” His words echoed what I had read that same morning, in a Mexico history book. Water isn’t just a present tense — it is an entire history and culture of disturbance.

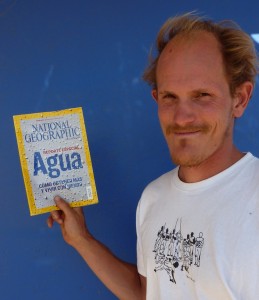

But the final surprise was his gift to me. Back in Los Angeles, after the Water Photography exhibit, I had searched the bookstores in Century City for the National Geographic special edition on water — but it was sold out. I left the U.S. without ever finding a copy of the magazine. In this little ranch house in Baja, Frederico pulled out the same magazine and said, “Here. I have already read it. Now it is your turn.”

Indeed, it was my turn.