This story originally appeared June 17, 2009.

At the start of 1981, Ronald Reagan moved into the White House and named James Watt secretary of the interior. Almost immediately, Watt became the bête noir of liberals — particularly environmental liberals — across the land. Within months, Watt announced an ambitious program that would have expanded offshore energy development into the Pacific and the Atlantic and resulted in the lease of the rights to extract oil and gas from under as much as a billion acres of sea bottom over five years. Watt’s plan drew immediate and harsh criticism, not just from the expected environmental quarters but even from several major oil companies, whose executives suggested — to the apparent surprise of Secretary Watt himself — that the expanded leasing might be too much for the industry to handle.

In July 1981, Watt swatted aside the critics, insisting that the program would go forward and ridiculing a survey by the National Wildlife Federation that showed its members strongly opposed the plan. According to an Associated Press report from the time, Watt called the survey “rigged” and “hilariously funny,” and said he’d dismissed it after looking at its first question. He likewise dismissed suggestions the program would outstrip the industry’s capacity to drill, saying, “We believe the marketplace will create the capacity.”

At a news conference, Watt also said he was going ahead with “area-wide environmental assessments and lease offerings of entire planning areas” because these would encourage energy development and foster a more efficient use of tax dollars.

In a series of reactions, the courts, then Congress and eventually the first President Bush restricted federal offshore energy exploration to the central and western Gulf of Mexico and minor developments off Alaska. But even though he was frustrated in his grand ambitions for expanded offshore exploration, Watt did fundamentally change offshore policy — in ways that have survived to the present.

The federal government gets revenue from offshore lands primarily in two ways: competitive “bonus bids” from companies to lease the right to search for oil or gas; and royalties, a percentage of the value of oil or gas actually extracted. Before Watt took over the Interior Department, only a limited number of blocks within an offshore area had been offered in each offshore lease sale. The selection of blocks was based on the resource assessment conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey and an ensuing indication of interest by the energy industry.

Watt moved to “area-wide” leasing, where all of the blocks in a given area (say, the entire central Gulf of Mexico) were offered at each lease sale. Before area-wide leasing, the record number of acres offered (Gulf sale 37, February 1975) was 2,870,344. The first area-wide sale offered up 37,867,762 acres, or more than 13 times as much ocean floor. With entire areas being put up for sale every year, suddenly only the multinational oil companies had the economic resources to contract seismic surveys on most of those areas. Smaller companies couldn’t keep up, and the federal government does not conduct independent offshore surveys. In practice, Watt’s area-wide leasing program set up a situation where the primary buyers (major oil companies) knew the potential value of a given tract, but no one else did — not even the federal government.

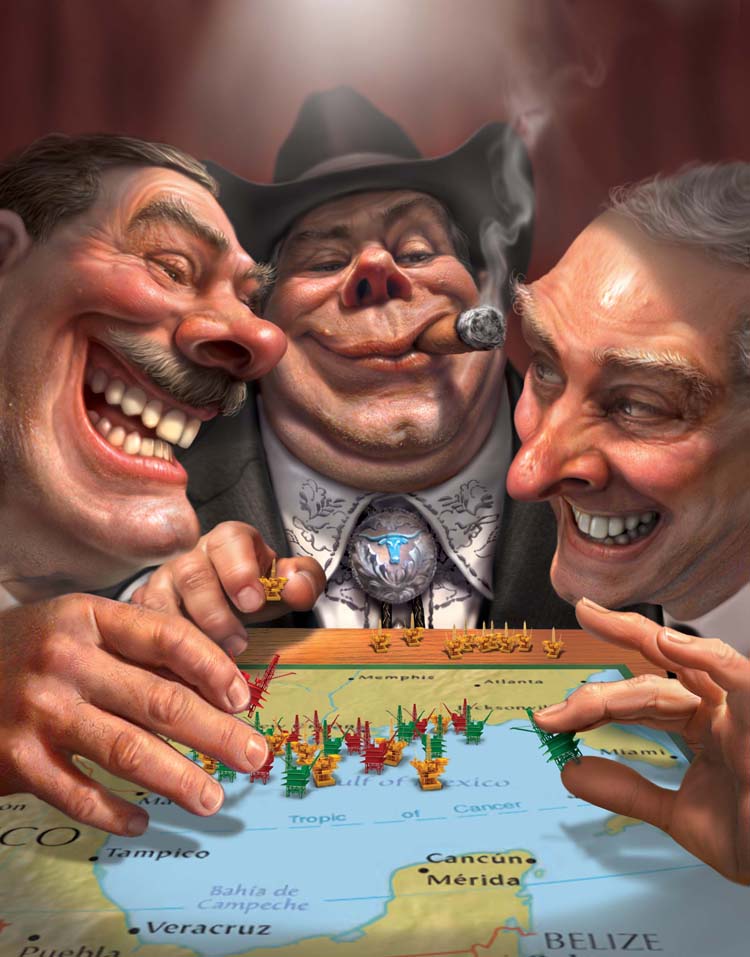

Area-wide leasing suppressed competition for offshore lands, allowing those in the know to offer minimal bids on promising blocks. More tracts were sold, but they were sold with fewer bids per tract and at bargain-basement prices. Now, more than 400 companies own all or part of a federal offshore lease, but more than half of these holdings belong to just 20 companies.

In the 25 years after Watt’s program was introduced, area-wide leasing has greatly reduced what oil companies pay for the right to drill offshore — and, correspondingly, greatly cut the per-acre income the government earns through its leasing program. In effect, area-wide leasing was a huge subsidy for major oil companies. How huge? Our research shows that per-acre lease rates plunged from an average of $2,224.71 for all federal leases identified as being sold from 1954 through 1982 to an average of $263.33 for the leases sold since Watt’s area-wide leasing went into effect.

But there’s more. The other main revenue stream the federal government receives from offshore oil and gas production — royalties — has also declined as a result of policy changes that began in the Watt era. In this case, though, Congress later expanded Watt’s policy changes — even though the U.S. has always required a lower rate than most offshore producing countries.

Before Watt, offshore leases specified that the federal government receive one-sixth of the value of offshore resources extracted (16.66 percent). In contrast, the state of Alaska — where oil extraction is scarcely cheap or easy — receives 22.5 percent on state leases. When area-wide leasing started in 1983, a number of leases were sold with royalties on one-eighth of the resource value, or 12.5 percent. These lower rates were generally for leases with greater water depths; they were offered in an attempt to encourage exploration in deeper areas of the Gulf of Mexico. Even though these rates were barely half of those being charged in Alaska, Congress decided in 1995 to provide “relief” to the oil companies, passing the Outer Continental Shelf Deep Water Royalty Relief Act, which allowed the companies to produce millions of barrels of oil and billions of cubic feet of gas without paying a nickel’s worth of royalties.

As the Government Accountability Office noted in 2007, if we look at total revenues collected on behalf of the 300-plus million Americans who actually own the nation’s offshore oil resources, “the U.S. federal government receives one of the lowest government takes (in the world).” In Norway, the total federal take is 76 percent. Maybe it’s time to take a look at how the U.S. got to be so out of kilter with other industrialized countries and to ask whether this is the way we want to go forward onto new offshore lands.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Colonel Edwin L. Drake brought in the world’s first oil well in Titusville, Pa., almost exactly 150 years ago, in August 1859. In ensuing decades, demonstrating that invention can also be the mother of necessity, the expansion of the market for petroleum products was to bring about the transformation and dependency of industrial society, the search for oil touching off a process that would ultimately result in the creation of the most powerful multinational corporations the world has ever seen.

During the first three decades of the 20th century, the search for oil tentatively expanded to reserves that were being discovered under coastal water bodies. By the 1940s and 1950s, this tentative search shifted to aggressive exploitation and to lands beneath the coastal seas. Since then, offshore oil and gas have become mainstays of world energy production. Today, most of the promising petroleum resources of the U.S. lie offshore.

The Gulf of Mexico was the proving ground for offshore oil, and the United States was the clear leader in the development of the technology that facilitated offshore energy exploitation. Many of the major corporations that were spawned in an extraordinary technological development curve during the 1960s and 1970s continue to dominate the field today. Unfortunately, technological expertise in offshore exploration and wisdom about the conservation of natural resources are not necessarily linked. The U.S. exploitation of its offshore resources is a model that has been adopted eagerly by Third World countries — but rejected by many other industrialized countries.

Legislation enabling offshore development in the United States was passed during the early 1950s; it designated the Department of the Interior as the agency to manage U.S. offshore lands. A quarter-century later, under James Watt, this management responsibility was placed in a newly created Interior agency with a name that left little question about its intended orientation — the Minerals Management Service. Since then, the leasing process has continued to evolve, almost completely privatizing the exploration for and the development and production of offshore energy resources. The government decides on the quantity of land to be leased and sets out royalty rates. Otherwise, however, energy companies hold most of the cards, deciding which tracts to bid on and explore based on survey information only available to the largest of those companies.

We began studying offshore leasing of public land for energy exploration in the mid-’80s, when one of us was on the Minerals Management Service’s Scientific Advisory Committee and the other was on the committee that the National Academy of Sciences established in response to a request from the first President Bush to examine offshore leasing issues in Florida and California. In addition to the research we did as members of those committees, we began collaborating with one another while exploring the socioeconomic effects of offshore petroleum activities on coastal communities. We expanded that collaboration to examine policy issues associated with offshore energy production and to explore the reasons why offshore activities are welcomed along some U.S. coastlines and emphatically resisted along others.

We started to wonder what area-wide leasing might mean for the official owners of all that offshore oil — the American public —in the early days of the policy. Only in the last year, though — now that the Watt-era policy has been in effect for about as long as the preceding policy, permitting a meaningful comparison between the two leasing regimes — did we decide to turn our attention to leasing policy in a more systematic way.

We’re both old enough to think of ourselves as being pretty skeptical toward the claims made by officials instituting new government policy, but even so, what we’ve been learning about Watt’s area-wide leasing program has surprised us. Since area-wide leasing went into effect, the number of leases of offshore lands sold has skyrocketed — placing into even sharper relief just how much the dollar amounts have dropped. Before area-wide leasing in 1983, 3,520 leases were sold at the $2,224 average rate, while 21,179 were sold from 1983 to 2008 at the $263 rate. Despite a roughly sixfold increase in the number of leases sold — to say nothing of the fact that inflation has taken a huge bite out of the value of the dollar since 1983 — the oil companies have actually paid the rest of us, the American taxpayers, fewer total bid dollars under Watt’s system than under the rates that were in place up to 1983. It is impossible to calculate how much money the federal government lost due to this change in leasing practice, but it is virtually certain that under the much more restrictive model in effect before Watt, the U.S. would have made more money, yet still have many more highly desirable leases left to sell. Whatever its other characteristics, what area-wide leasing seems to do best is to transfer huge swaths of public land into the hands of the world’s largest oil companies at some of the world’s cheapest prices.

At the same time, the changes in offshore management practices instituted in the Watt-Reagan era clearly have failed to achieve their originally stated energy goals. In early 1982, Watt saw the offshore leasing program as “one of America’s best hopes for a secure and strong energy future.” Ever since that time, however, domestic oil production has been falling, not rising. The U.S. now imports about twice as much oil as it did in the 1980s.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Today, there are more than 4,000 offshore production facilities in the federal waters of the central and western Gulf of Mexico, about three-quarters of them off Louisiana. They are served by more than 25,000 miles of buried pipelines. There is no production in the eastern Gulf (off Florida). The evolution of this massive industrial process over the six decades since Kerr-McGee‘s first successful well began production in 1947, on a lease from the state of Louisiana, has radically transformed coastal Louisiana and, to a lesser extent, Texas.

If new offshore development goes into frontier areas, there will be social, economic and environmental effects, but they will probably not be what most people think. We start with the good news:

• The probability of a major oil spill is lower than most people think. The evolution of offshore exploration and production technology has been paralleled by evolution in spill-prevention technology. With the ability to shut down the flow of production automatically when well pressure is lost with fail-safe valves at the sea floor, in the last several decades few major spills have been seen in the Gulf. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita both packed sustained winds of more than 170 miles per hour, sending waves that may have been as tall as 10-story buildings right through some of the heaviest production areas in the Gulf. A total of 113 production platforms were destroyed and 50 were heavily damaged. Five mobile offshore drilling units were destroyed, 19 were extensively damaged and three remain missing. A total of 457 pipelines were damaged — 101 of them having been major ones — 10 inches or greater in diameter. Some of these pipelines were damaged as mobile offshore drilling units were driven before the storms’ winds, dragging their massive anchors across the bottom. All of the fail-safe valves apparently worked, however, meaning that oil spills were limited to oil in the ruptured pipelines or in the risers to damaged platforms. Although more than 700,000 gallons spilled from 124 sources in these extraordinary events, there were apparently no uncontrolled well flows.

Any time oil is produced or transported, there is the possibility of a spill. The Atlantic can bring hurricanes ashore, and the storms that form in the Gulf of Alaska and hit the Pacific Northwest are not trivial affairs either. Off the North Slope and into the Arctic Ocean there will be as yet unknown challenges, particularly with declining sea ice. Still, the industry truly does deserve credit for improvements that have been made in preventing oil spills since the infamous Santa Barbara blowout in 1969.

• No matter what the extent of the resource discovered in the Atlantic, Pacific or Arctic, the resulting local physical infrastructure — primarily production platforms and fabrication yards to build them — will be only a small fraction of what it is in place in the Gulf of Mexico. In the earlier days of Gulf production, drilling technology was primitive by today’s standards. A large reservoir required a number of platforms to be sited over it; wells had to be drilled vertically to tap the oil or gas. Today, with directional drilling, production wells can be drilled vertically into the reservoir and then turned horizontally or even upward toward the surface to drain the reservoir. Many more wells can be drilled from one production facility and fewer offshore production facilities are needed.

Not all of the offshore-drilling news, however, is likely to be good, especially on the financial front and especially not for the land areas closest to new exploration:

• Whatever the extent of resources discovered in new frontier areas, the local positive economic benefits associated with the exploration, development and production will also be far less than those in the Gulf of Mexico. Production facilities are no longer likely to be built locally because they are, by their very nature, mobile. They are built onshore or in a port and then towed offshore. Accordingly, they can be built virtually anywhere in the world and installed virtually anywhere else. The primary portion of one of the larger production platforms in the Gulf was built in Italy. Fabrication yards that specialize in producing offshore facilities already exist in the Gulf of Mexico, in Norway, in Italy, in Korea, in Newfoundland and elsewhere.

Decisions on where to build the facilities depend in part on the physical infrastructure (massive cranes, pipe-bending facilities and more) associated with the yards that build these huge structures. An even more important factor is the presence of a highly specialized local labor force that has grown up with each new adaptation in fabrication technology. Any production platforms needed for the Atlantic would probably be built in the Gulf. There will certainly be no fabrication yards on the North Slope, and it is unlikely there will be any on the West Coast.

But not even the jobs associated with the more labor-intensive exploration and development phases for new development are likely to be local. The mobile drilling rigs for exploratory and developmental drilling already exist, more are under construction in the Gulf, and they are regularly towed to wherever they are needed. The workers who staff these rigs learned their skills primarily in the Gulf, but they follow the rigs wherever they go. This is possible because of the scheduling associated with offshore work. The typical pattern is for crews to meet at a prearranged place to go offshore for two weeks. While on the job, individuals work 12 hours on and 12 hours off. At the end of two weeks, people are off for two weeks. This schedule means that an individual only has to commute once a month — allowing him to live almost anywhere in the country and commute to almost anywhere else. Very few of the approximately 6,000 individuals who work in the petroleum sector on the North Slope live there; many live in Louisiana and Texas. The individuals who work offshore in the Gulf live in states as far away as New York and California. When offshore oil expanded internationally, the work schedule also expanded. There are a number of Louisiana residents who work 90 days on and 90 days off in Nigeria and elsewhere. This reduces the commute to twice a year.

With new exploration, there will be some local economic activity — new helipads for ferrying workers offshore, for example, or new loading facilities for offshore supplies — but these will in all likelihood be minimal. All of these trends, or non-trends, are predictable and should be taken into account before new leasing commences.

• Whatever the additional resources discovered offshore from the United States, they are extremely unlikely to significantly change world supply and, hence, world oil prices. The U.S. produces less than 7 percent of the world’s oil. Even if this could be raised to 10 percent — an almost impossibly optimistic hope, given that U.S. production has been declining since 1970 — it would still amount to little more than a trivial fraction of world production. If the price of oil is driven by supply and demand, then this additional supply would probably produce an imperceptible result on world market prices. What it would do, reliably, is to reduce even further the tiny amount of oil still left on U.S. lands. Today the U.S. has only about 2 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves.

• Any resources discovered in the frontier U.S. offshore are extremely unlikely to change U.S. dependency on imported oil. Known reserves in the Gulf of Mexico dwarf those in all other offshore areas, and “undiscovered technically recoverable reserves” (the Minerals Management Service’s best guesses about remaining amounts of oil) are greater in the Gulf than in all other U.S. offshore areas combined. Still, offshore production in the Gulf has been going on for more than half a century, meaning that remaining reserves are only a fraction of the original amounts. Outside of the Gulf, the projections for future resources are by far the strongest in Alaska and weakest in the Atlantic. Given the time period needed to bring undiscovered resources on line and the continued decline in U.S. production, it is doubtful that the full exploitation of Alaska, the Atlantic and the Pacific could even stop the continued decline in total U.S. production, let alone turn it around.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

As oil prices continued to climb during the 2008 presidential campaign, eventually hitting a price of more than $147 per barrel, Republican presidential candidate John McCain emphasized the importance of bringing down prices for oil and gasoline with his “drill here, drill now” rhetoric, encouraging expanded offshore production. As the campaign progressed, the rhetoric morphed, becoming the more euphonious “drill, baby, drill,” and President George W. Bush ended the presidential moratorium that had prevented offshore oil drilling along most of the nation’s coastline for more than a decade. Shortly thereafter, the Democratic leadership in Congress allowed the congressional moratorium to expire as well. Expanded offshore exploration is almost certain to be a major focus of the 111th Congress. Even under the new Obama administration, the Minerals Management Service is moving toward an Atlantic lease sale of 2.9 million acres off Virginia. This, in short, would seem to be a good time to recognize that the existing model for managing America’s offshore assets — with low royalty rates and area-wide leasing — seems better at transferring valuable undersea resources to a handful of the richest corporations in history than at maximizing the value of those resources for taxpayers or turning around our dependency on imported oil.

To improve the way the U.S. exploits its remaining offshore reserves, at least three changes in Interior Department management strategy are necessary:

• The Interior Department needs to become actively involved in the assessment of the potential for offshore areas, probably through the U.S. Geological Survey. This will mean the government actually funds offshore seismic surveys, interprets their results and makes the analysis public. Without such surveys, Interior is “selling blind” — that is, leasing public property with little idea how much it is worth.

• Based on survey data and expressions of industry interest, the Minerals Management Service should return to offering a much more limited selection of tracts for offshore sales. This reduction in the areas put out to bid will spark competitive bidding again and let federal policy, rather than private speculation, guide new offshore activities on public land.

• Finally, the Department of the Interior should examine royalty rates for other global offshore areas and increase U.S. rates to mirror those paid in the rest of the world.

Ironically, many of the same politicians who defend the “free-market system” are the ones who voted to allow “royalty relief” for wells sunk in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico. This move into deep water produced some of the most profitable oil wells in the history of the Gulf — meaning, in retrospect, that no such “relief” was actually needed.

Energy companies explore for oil all around the world, and much if not most of the time, they pay higher royalties elsewhere. The 2007 GAO report noted earlier considered the results of a number of studies, concluding that the federal government receives one of the lowest government takes — that is, the combination of bonuses, rent, royalties, corporate income taxes and special fees or taxes — in the world. “Collectively, the results of five studies presented in 2006 by various private-sector entities show that the United States receives a lower government take from the production of oil in the Gulf of Mexico than do states —such as Colorado, Wyoming, Texas, Oklahoma, California and Louisiana — and many foreign governments,” the report said. The Minerals Management Service no longer sells leases at 12.5 percent — a step in the right direction — but “royalty relief” is still in effect at the discretion of the agency.

Oil companies are in the business of making money off the exploitation of petroleum. If a particular discovery is not judged to be profitable enough to exploit because it is too small or too deep — or for any other reason — then perhaps the federal government should not be subsidizing these companies to drain the reserves in a hurry. The resource isn’t going anywhere, after all; ultimately, with the rising price of petroleum and advancing technology, the companies will get around to it — when they can make a profit!

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.