As one of the most wildly successful species on planet Earth, humans have left their mark on nature: paving over forests, filling the oceans with plastic pollution, and pouring planet-warming gases into the atmosphere at an unprecedented pace. But one area that’s often overlooked in discussions of the ways humans threaten the environment is our food supply.

Today, there are nearly 7.7 billion people on Earth, and it takes almost half the world’s vegetated land to feed them all—or almost all of them anyway. About one in 10 people around the globe still suffers from chronic hunger, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. The agriculture sector already generates a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions every year, and the global population is expected to balloon to nearly 10 billion by mid-century, right around the time that global emissions need to reach net zero, which raises the question: How will we feed them all?

There’s no easy answer, according to a new report from the World Resources Institute, which finds that reforming the agriculture industry isn’t just critical for feeding the world, but for saving it from climate change as well.

“Food is the mother of all sustainability challenges,” Janet Ranganathan, the vice president for science and research at WRI, told reporters last week, citing agriculture’s contributions to nitrogen pollution, deforestation, biodiversity loss, water use, and greenhouse gas emissions. “We can’t get below 2 degrees without major changes to this system.”

The World Bank Group, the United Nations Environment, the United Nations Development Program, the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development, and the French National Institute for Agricultural Research all contributed to the report, which identified three “gaps” that need to be closed in order to feed the world in 2050, while keeping temperature increases in line with the Paris Agreement.

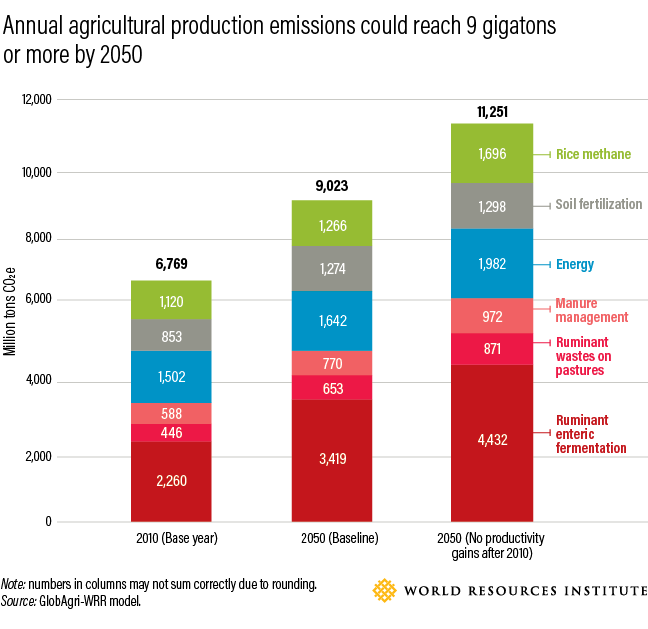

Using 2010 as a baseline, the analysis found that, by 2050, the world’s population will need 56 percent more food and some 1.4 billion more acres of land—an area twice the size of India. Agriculture emissions are expected to rise to 15 gigatons a year by mid-century, but to stay in line with the Paris Agreement, the sector’s emissions need to fall to 4 Gt a year.

Closing those gaps “requires producing more than 50 percent more food, doing so on the same amount of land, all while lowering today’s greenhouse gas emissions by two thirds,” according to WRI’s Tim Searchinger, the lead author on the report. Searchinger and his co-authors outlined several strategies for producing more food while shrinking the agricultural industry’s footprint.

Increasing Yields

(Chart: World Resources Institute)

Massive gains in crop yields between the mid-20th century and today came from a mix of targeted breeding, fertilizers, and converting hundreds of millions of acres of forests and savannas to farms. To produce more food on the same amount of land, crop yields need to keep rising.

Breeding to create high-yield crops is already responsible for half of historical yield gains, according to the report, and both breeding and the more direct approach of gene editing could keep harvests climbing in the future—and protect crops from climate extremes by creating heat- or drought-tolerant plants.

Breeding more desirable traits into crops can also increase profitability, and create a new threat to vulnerable land. “Boosting of yields of soybeans, for example, helped lead to the clearing of lands for soybeans in Brazil,” Searchinger said. Similarly, as oil palm yields increased in Southeast Asia, so too did rates of deforestation, so yield gains need to be paired with efforts to protect forests.

It’s not all about producing more food; it’s also about wasting less. About a third of all the food grown around the world goes to waste, according to the new report. If food losses were cut by just a quarter, it would reduce the food gap by 12 percent, and bring us 15 percent closer to closing the emissions gap.

Cutting Down on Meat

Swapping our meat- and dairy-heavy diets for more plant-based meals could have a huge effect on these gaps as well, because animal-based foods require more land and produce significantly more greenhouse gases per calorie than plant-based ones. Though the WRI report was not released in time to influence COP24’s menu planners, Farm Forward, a food sustainability non-profit, along with the Center for Biological Diversity and BrighterGreen, analyzed the menu at COP24 and noted that meat-based meals were twice as common as plant-based ones. If the conference attendees all opt for meat-based meals, that would mean more than 4,000 metric tons of additional emissions—about as much as 3,000 people flying from New York to Katowice.

“The meat-laden menu at COP24 is an insult to the work of the conference,” Stephanie Feldstein, director of the Population and Sustainability program at the Center for Biological Diversity, said in a statement. “If the world leaders gathering in Poland hope to address the climate crisis, they need to tackle overconsumption of meat and dairy, starting with what’s on their own plates.”

Demand for meat around the world is projected to rise 68 percent by 2050; demand for ruminant meat, which includes cows, goats, and sheep, could climb by nearly 90 percent. “If global consumers shifted 30 percent of their expected consumption of ruminant meat in 2050 to plant-based proteins, the shift would, by itself, close half the [greenhouse gas] mitigation gap and virtually all of the land gap,” the report states.

Consumer behavior is already changing: In the United States and Europe, beef consumption has dropped by about a third since the 1960s, according to Searchinger, replaced largely by chicken. “Younger consumers are growing up with a different attitude toward meat,” Kevin Brennan, the chief executive officer of Quorn Foods, a company that makes meat-substitute products, said in the press briefing last week. But, Brennan says, it’s going to require a government intervention—like a “meat tax”—to get behaviors to change as quickly as they need to. Eliminating the subsidies to U.S. farmers who produce beef, for example, could double the price of the meat for consumers.

Ultimately, closing the gaps outlined in the report will require a combination of yield gains, agricultural innovations, ecosystem protections, and changes to human behavior.

“The gaps between where we are and where we need to be have become so large and the timeline so condensed we have no choice but to turn over every stone and push in every direction,” Tobias Baedeker, an agricultural economist at the World Bank, said last week.

“We’re going to have three billion more mouths to feed, and those mouths will increasingly be consuming more resource-intensive, animal-based foods as global incomes rise,” Ranganathan said. “We have to change how we produce and consume food, not just for environmental reasons but because this is an existential issue for humans.”