In 2004, cognitive neuroscientist Itiel Dror and Dave Charlton, a veteran fingerprint examiner and doctoral candidate, chatted over coffee in a Brighton hotel suite after a gala dinner at the U.K. Fingerprint Society’s conference. Charlton was upset. Months earlier, Dror had designed a study to see if fingerprint examiners’ decisions on matches might unconsciously be biased by information they received about a case.

Would examiners change their opinions about prints they’d called matches five years earlier, Dror wondered, if they viewed them again in a different context?

Charlton, supervisor of a U.K. police department’s fingerprint lab, editor of the Fingerprint Society’s journal Fingerprint Whorld and a true believer, was certain they would not. He urged Dror not to waste his time.

But Dror was insistent: “I said, ‘Indulge me! Let’s do it.'” And so, five international experts were put to the test covertly, re-examining matched prints from their own old cases while armed with different — and potentially biasing — “case information.” They’d agreed to be tested, but they didn’t know when — or even if — test prints would cross their desks.

That night in Brighton, the results were in. For Charlton, they were a jaw-dropper.

“Not only some, but most, of the fingerprint examiners changed their minds,” said Dror, who was far less surprised by the flip-flopping. As an expert in human thought processes and the hidden power of cognitive bias — an array of distortions in the way humans perceive reality — he had a decided advantage.

Fingerprints have been accepted as unassailable evidence in courts for more than 100 years, but vaunted claims of their uniqueness and infallibility still lack scientific validation. By contrast, the existence of cognitive bias and the subjective nature of human judgment have been thoroughly established by hundreds of scientific studies going back decades.

Dror knew the ways in which unconscious bias could impact expert decision-making, yet allowances were rarely made for it in the work of fingerprint or other forensic examiners. Then, in February, a landmark National Academy of Sciences report on forensic science called for massive reform. The report, which cited Dror’s studies, sent a strong message about the need for research into the effects of cognitive bias and finding ways to minimize it.

Dror, who is affiliated with the University College of London and has a consultancy and research company (Cognitive Consultants International), has long yearned for forensic science folk to collectively pull their heads out of the sand and accept the obvious: Some of their work is unarguably subjective.

Bait and Switch

In today’s fingerprint world, scanners, not ink, collect prints, and gigantic automated databases — like the FBI’s Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System — spit out the closest matches in seconds. IAFIS has the prints of more than 55 million subjects in its Criminal Master File.

Still, television’s CSI this is not. Despite all that technology, it then falls to fallible human beings to step in and make visual comparisons and the ultimate judgment calls on matches.

Although forensics experts routinely claim otherwise, “You don’t have to be an expert in cognitive neuroscience to know that this kind of interpretation, evaluation and judgment of visual pattern is definitely not objective,” Dror said.

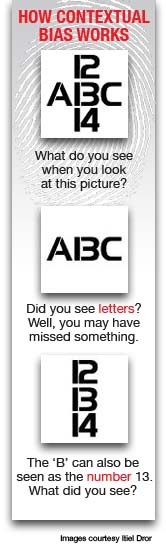

The human factor opens the door to all kinds of contextual influences and biases because, he explained, “many times, when we process visual information subjectively, it depends on the context and who we are, what we expect and a whole variety of basic, well-established psychological and cognitive phenomena. And somebody saying that human judgment and perception is totally objective is like saying the Earth is flat. You can’t believe it when you hear that.”

It’s not that forensic experts are any more biased than any other experts whose work involves human interpretation and judgment, but experts in fields like medicine, finance and the military increasingly acknowledge bias and take steps to counter it.

In Dror’s study with Charlton, the five experts were told they were seeing the erroneously matched fingerprints of Brandon Mayfield, the Oregon man once linked to 2004’s terrorist train bombings in Madrid. That he’d been wrongly accused based on fingerprint misidentification was widely known, thus suggesting what an expert determination would be.

What they were actually seeing, however, were fingerprints from other cases that they’d made determinations about years before.

“What I did was, as we say in England, a bit tricky,” Dror recalled, “and very innovative. I wanted to compare the same experts. I wanted the same expert to make a judgment on exactly the same fingerprint, but use different context.”

Three of the five reversed their earlier conclusions to say “no match,” and one deemed the prints “inconclusive.” Only one expert stuck with his original decision. Although the study group was small, this kind of within-subject research, testing someone against themselves, is considered especially powerful.

The result left Charlton very conflicted. His brief jolt of elation — the research was on to something important — was tempered by sorrow. “I felt like I shot my profession in the foot,” he recalled. “I felt very concerned and sad.”

He was hardly alone in his total faith in fingerprints. Yet, while fingerprint identification is an invaluable, largely reliable police tool, there are several reasons it cries out for serious scientific study. Latent prints — impressions lifted from crime scenes with techniques like dusting — are routinely smudged, degraded, distorted and incomplete. And low-grade latent prints are not only vastly inferior for matching purposes, they are also, Dror’s research shows, those most at risk for error and unconscious examiner bias.

What is more, there are no uniform minimum standards on acceptable partial prints or on the points of similarity required for a match.

When Dror began his various studies, cracks were already appearing in fingerprint analysis’s facade of perfection; recognition that it was important to establish a scientific error rate was building. It would be nice to know if fingerprints (or snowflakes, for that matter) are unique, as we’ve long believed. However, uniqueness is far less important for justice than knowing if enough fingerprints are sufficiently similar to fool experts and just how often this might happen.

And with today’s massive automated fingerprint identification systems, that concern is more reality than fantasy. Just ask former police constable Shirley McKie of Strathclyde, Scotland.

Even an Innocent Suspect Accepted Infallibility

In 1997, four Scottish fingerprint experts claimed they had found McKie’s left thumbprint — one of 400 prints collected as evidence — on the bathroom doorframe in the home of murder victim Marion Ross. When McKie, a junior officer conducting interviews in the area, insisted that she’d never been inside the property, she was accused of lying.

Initially, McKie believed it was all a simple mistake that would soon be corrected. But in 1998, she was arrested and charged with perjury. If guilty, she’d face several years in prison. Despite this, her faith in fingerprints did not waver. She didn’t doubt that the print was hers, but she was completely mystified by how it got there. Could she have touched a door-facing in a lumberyard while shopping, she wondered?

“For the first two years, I really believed that the print was mine and must have somehow been planted or forged,” Shirley McKie told Miller-McCune.com via her father, Iain McKie, a former police superintendent who fights tirelessly to clear his daughter’s reputation. “Fingerprinting was seen as the gold standard of forensics, and as a detective, you learned that when an accused person was identified by a fingerprint, they were guilty — end of story.

“Sadly, I now know different.”

The sole forensic evidence against Marion Ross’ accused killer, David Asbury, was also a single fingerprint. A jury found him guilty, but the verdict was later quashed because the fingerprint evidence against him was considered unreliable.

Vindication for Shirley McKie first came in 1999 when renowned U.S. experts Pat Wertheim and David Grieve categorically determined that the print was not hers, and she was acquitted of perjury. In 2006, she was awarded £750,000 in a civil case.

But despite McKie garnering enormous international support from other experts, the Scottish Criminal Records Office still has not conceded any error. In fact, Shirley McKie said, the SCRO (now part of the Scottish Police Services Authority), “will not accept, even today, that it is not my print.”

Fiona McBride, one of the original Scottish examiners, has never acknowledged any error or wrongdoing. And in 2008, despite the cloud over her name, she was made editor of the Fingerprint Society journal, Fingerprint Whorld, a move that a disgusted Iain McKie believes opened the organization to international ridicule.

Three years after the Ross murder, Assistant Chief Constable James McKay recommended some in the SCRO should face prosecution. His recommendation was ignored, and until 2006, the report was kept secret.

Hearings in the judicial inquiry Iain McKie long campaigned for are now underway.

Meanwhile, in a landmark U.S. case, Stephan Cowans of Boston became the first person to be convicted on fingerprint evidence, then — after serving six years in prison for shooting a police officer — exonerated by DNA. Two prosecution experts and Cowans’ two defense experts (formerly of the same fingerprint unit) had all verified the match. After his 2004 release, Cowans revealed his earlier certainty about fingerprints by saying that on the evidence presented in court, he would have voted to convict himself.

Very Public Example

Fingerprint evidence’s biggest blow came with a huge international embarrassment for the FBI: the case of Brandon Mayfield.

Mayfield, 37, an Oregon lawyer and Muslim convert, was arrested as a material witness after the devastating terrorist train bombings that rocked Madrid in March 2004. The FBI’s Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System turned up 20 possible matches to a partial print on a plastic bag of detonator caps found nearby. Three FBI agents were certain that Mayfield’s prints, in the system after a teenage arrest, were a match. Mayfield’s court-ordered, independent expert concurred.

While Mayfield spent two weeks behind bars, skeptical Spanish authorities chased other leads, ultimately determining that the print belonged to an Algerian, Ouhnane Daoud. Chastened, the FBI backed down and even apologized to the Mayfield family. Mayfield, who was sure he was targeted because of his faith, was later awarded $2 million in damages.

The FBI called the points of similarity between Mayfield’s and Daoud’s print “remarkable.” But, Jennifer Mnookin, vice dean and law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, points out that we have no idea, let alone solid data, on how common such similarities might be. The small number of fingerprint errors that come to light doesn’t mean that there aren’t many more. And it troubles Mnookin that, “at root, fingerprint identification is a probabilistic enterprise.” (She is collaborating with Dror on a paper about the challenges and risks arising from fingerprint identification databases.)

Even if we knew — which we don’t — that fingerprints are discernibly unique, “that doesn’t begin to answer the question,” Mnookin said, “of whether latent print examiners, using their techniques and methodologies on partial prints that could well have smudges and distortions, can accurately link that partial print to one person to the exclusion of all others.”

John Massey, one of the original FBI examiners on the Mayfield case, acknowledged knowing that another examiner had already called the prints a match before he saw them himself but claimed that he felt no pressure to reach the same conclusion. Calling the identification error an honest mistake, in October 2004 he told the Chicago Tribune, “I’ll preach fingerprints till I die. They’re infallible. I still consider myself one of the best in the world.”

Dror believes that the Mayfield arrest was influenced by a very emotionally charged situation, with 191 killed and approximately 2,000 injured in an act of terrorism. And an FBI investigation concluded that its examiners were influenced by the urgency of the situation to confirm the match. An investigation by the Department of Justice’s Office of the Inspector General (see PDF here) found no FBI wrongdoing but acknowledged that bias played a role in the error.

The very power of the FBI’s IAFIS likely also contributed, Dror believes. He sees automated fingerprint identification systems as both goldmine and landmine, since the size of their holdings increases the statistical chance of finding very similar fingerprints.

“It enables you to look at millions of prints very quickly, make quite good comparisons; it enables you to resolve cold cases and is very good in many ways,” he said. “However, that same powerful technology that helps solve crimes has also increased the likelihood of finding very similar fingerprints by accidental coincidence.” He believes that prosecutors should compensate for this in trials that hinge on IAFIS matches by producing more supporting evidence.

Clearly, more research is critical. Meanwhile, as the only fingerprint experiments to use covert data collection, Dror considers his study models “very, very powerful from an experimental, scientific point of view. It’s very strong statistically because it’s within-subject design.”

“Itiel is a terrific incubator for ideas,” Mnookin said. “He’s very much what the field needs.”

Nobody’s Fault, Everybody’s Concern

Dror’s fingerprint study participants all signed on to be included but had no clue when, if ever, they would be tested. That eliminated one very key research problem: If people know they are being tested, and on what, they behave differently.

“Especially if you tell them, ‘Oh, we’re going to collect data to see if you’re biased in your decision-making.’ If you want to know how I drive, don’t observe me during a driving test because I drive really nicely and obey all the laws, and I slow down,” Dror said. “If you really want to know how I drive, observe when I think nobody’s looking.”

In another study, his team had six international experts each view eight latent prints that they’d each previously examined, but now they were accompanied with a new, mundane context — something like, “the suspect has confessed,” or, “the suspect is in custody.” More expert reversals followed. Four of the six reached different conclusions. One changed his mind three times.

Dror is at pains to explain that bias is not a fault, it is simply the way the human mind works, and in experts, an unavoidable, inherent outcome of their very expertise. Nonetheless, it must be recognized, accommodated — and studied. Predictably, he and his insights can be about as welcome as a bad flu among some forensic scientists.

“Here is an academic scientist telling them that they’re making mistakes from time to time when they’ve been told they never make mistakes if they follow their methodology,” Dror said.

And while fingerprint evidence has taken some big hits, that hasn’t stopped a number of U.S. courts from reaffirming its reliability since the FBI apology to Mayfield.

The resistance to giving cognitive bias serious consideration was glaringly apparent in a 2007 letter to the editor of Fingerprint Whorld from Fingerprint Society Chairman Martin Leadbetter. It was sent in response to Dror and Charlton’s article, “Improving perception and judgment: An examination of expert performance.” Leadbetter’s letter disputed that emotional influence is a factor that can bias perception and judgment. He contended that, “…any fingerprint examiner who comes to a decision on identification and is swayed either way in that decision-making process under the influence of stories and gory images is either totally incapable of performing the noble tasks expected of him/her or is so immature that he/she should seek employment at Disneyland.”

In closing, Leadbetter wrote: “And I do find it rather unsavoury that those within our own ranks, who ought to know better and are aware just how reliable the fingerprint system is, continue to provide fuel for those within the media and Press who seem to relish attacking what is the most valuable tool in the investigating officer’s armoury.”

Dror, who accepts his role as a lightning rod for controversy and criticism, wrote a detailed rebuttal. (See the full exchange here.) Particularly after watching Charlton wrestle with his feelings, Dror knows it’s painful for the many dedicated, conscientious experts to accept that unconscious bias might have compromised their work or worse, possibly contributed to sending an innocent person to prison.

But far from Dror being forensics experts’ adversary, Mnookin, the UCLA law professr, said, “Itiel cares about being fair to them. I respect that about him.”

A Child’s Garden of Bias

Some may think that technological advances will soon reduce or eliminate fingerprint identification weaknesses. Not so fast, Dror said. The psychological and cognitive issues facing forensic science won’t be blown away by technology. First, human experts have abilities to compare fingerprints that technology does not, so humans will continue to play a critical part in fingerprint analysis.

Second, the biases that Dror talks about are unintentional and occur unconsciously, so they are not easy to detect and eliminate. Third, he said, biases can be in technology (computer programs are written by human beings, after all), and technology itself can introduce new biases.

Bias is a complex foe. An array of unseen influences may impact evidence results by affecting what examiners believe they see and diminishing their objectivity. And there are numerous cognitive and psychological biases to recognize and counter. As long as forensic examiners don’t make determinations about pattern matches “blind,” for example, they will be more vulnerable to what’s known as “confirmation bias.” Confirmation bias is where evidence is cherry-picked to emphasize what confirms preconceived ideas and what someone hopes or expects to see, and downplay what doesn’t.

“Conformity bias” — when examiners’ judgments and perceptions are influenced by others’ opinions or by peer pressure — is also common. “Authority bias,” another pothole, is where decisions may be colored by a superior offering an opinion and maybe exerting subtle pressure to concur. Experts also may get locked in to a line of thought, and that can bias an outcome — so can momentum or feeling pressure to solve a case or having an emotional reaction to gruesome crime scene images.

In a police environment, a fingerprint examiner might be motivated to find a match if they believe someone is guilty or know a detective is after a terrorist or pedophile. The possibilities to derail objectivity seem endless.

Quite simply, bias distorts the way we perceive and evaluate information. And while medicine and clinical research combat bias with blind and double-blind studies, thus far, the forensic community has favored the ostrich approach.

A key National Academy of Science report recommendation — to move crime labs out from under law enforcement’s wing and create a new national institute of forensic sciences — would surely help impartiality. If lack of funding delays that, “so be it,” Dror said. “But you can’t have it both ways. If there’s no reform, don’t say, ‘I am 100 percent objective, I make no mistakes, there is no problem.'”

In the interim, some steps can be taken. When further examiners are called on to verify the work of a first, they should always examine the evidence independently without knowing the earlier results.

Efficiency, scientific validity and objectivity could also be dramatically improved for a relatively small financial outlay by establishing and enforcing “best practices” in crime labs (another NAS report recommendation.) Best practices are formally documented standard operating procedures, processes and rules for how to do your work that are specifically designed to make it effective and efficient, and avoid error. Having best practices that all fingerprint examiners everywhere must adhere to would be a big step forward, Dror believes, but only if they are science-based and validated by experts in cognitive neuroscience, psychology and thought processes.

Today, guidelines are provided by Scientific Working Group on Friction Ridge Analysis, Study and Technology. However, these are only guidelines with no mechanism of enforcement. “What is more,” Dror said, “none of the current guidelines really directly and adequately deals with confirmation bias and other cognitive issues.”

While he favors more research all around, he cautions that new studies alone won’t be enough. They too must be impartial, bias free and conducted in neutral environments. And while some he sees are solid, the structures and goals of others seem foggier, more like what Dror calls “defensive research” — conducted in-house and seemingly constructed to show that “everything is hunky-dory and great, and there is no bias.”

Stephen Meagher, one of the FBI examiners to finger Mayfield, authored a controversial analysis of 50,000 pre-existing fingerprints. Each print was compared to itself and all others electronically, producing 2.5 billion comparisons and the claim that the chance of one person’s fingerprint being mistaken for another’s is fantastically remote. However, other scientific experts took serious issue, calling Meagher’s study and its conclusions bad science and, said forensic science scholar and fingerprint analyst David Stoney, “extraordinarily flawed and highly misleading.” (Page 28 on PDF link.)

In a 2004 letter to New Scientist, Meagher wrote that his study sought to establish that fingerprints are unique, not to reveal their error rate. To his critics, like Simon Cole, an associate professor at the University of California, Irvine, Meagher’s words are a clear admission that the FBI, courts and prosecutors who have since cited Meagher’s “50,000” study as evidence of fingerprint matching’s infallibility are therefore making erroneous assumptions about what the study showed.

Cole, a vocal critic of the claims of infallibility of fingerprint matching, told New Scientist in 2005 that Meagher’s replies to the magazine, “demolish claims that the 50K study is evidence of infallibility.”

Using proficiency test results of qualified fingerprint examiners, Cole put estimated false matches at 0.8 percent on average but, one year, likely as high as 4.4 percent. He has estimated that U.S. authorities could make as many as 1,000 incorrect matches per year.

U.K. law enforcement researchers Lisa J. Hall and Emma Player recently conducted a study with 70 volunteer fingerprint experts from the Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Bureau. Its stated aim was to learn if fingerprint experts were emotionally affected by a case’s circumstances, and if the written crime reports that routinely accompany latent prints affect examiners’ interpretations of poor-quality prints. Participants compared the same partial print on a £50 note and full set of fingerprints. Half were told the case involved forgery, the rest that it involved a murder.

First, participants self-reported their emotional reactions, then whether those reactions affected their decisions. Fifty percent of those given the murder context did feel affected emotionally, compared to only 6 percent of those given the forgery context. But the two groups’ final opinions and identification rates remained very close irrespective of context.

In a lengthy letter to the editor of Forensic Science International, however, Dror noted the researchers’ misunderstanding of cognitive processes and criticized the methodology. For example, he noted that when you’re trying to evaluate the effects of emotional context, participants must genuinely believe that the context they’re given is real and true in order to be fully influenced by it. In conclusion, he wrote: “… in-house self interest research aimed at validating and defending current practices does little-to-no service to the profession.”

The researchers’ own rebuttal letter then noted that the research, although in-house, used examiners that did not know the study’s aim, and that their primary focus was on the examiners’ final matching decisions. “The results of the research have illustrated that crime type has no significant effect on final decision,” they wrote. Based on the participants’ own reporting of the contextual effects on them, and on other research, Dror takes issue with that assumption.

“Not all contexts bias every examiner to modify their decisions,” he noted, “but some contexts, under certain circumstances, may affect certain examiners’ final decisions.”

Sharing law enforcement’s goal of putting the guilty behind bars and keeping innocents free, “I’m not here to make their lives difficult and to criticize,” he insisted. “But being a friend doesn’t mean what some of them want it to mean — kiss their behinds all the time and say they’re doing it wonderfully. Being a good friend sometimes is saying, ‘You’re making a mistake! I know you love that girl and you want to marry her, but because you’re in love you’re blind! And don’t shoot the messenger!'”

Testifying for the Beast

At his lectures, forensic experts often ask if he is biased in his research: “I say, ‘Of course I’m biased. Everybody’s biased.’ I’m less biased than somebody working on a murder or terrorism case, but I do have bias and subjectivity.”

Generally, Dror avoids testifying in court. But he made an exception for notorious British murder suspect Levi Bellfield, aka the “Bus Stop Beast.” Bellfield was accused of the bludgeoning murders of two women and vicious attacks on others. His defense counsel asked Dror to review the police experts’ examination of a single piece of evidence: a fuzzy, closed-circuit TV image of a vehicle license plate.

While the crimes Bellfield was accused of certainly sounded horrific, Dror’s focus was squarely on the rare chance to advance awareness of the possibility of bias in forensic evidence presented at criminal trials. “And when they said, ‘We want to introduce confirmation bias as a real issue in the court in the forensic domain,'” he recalled, “I thought it was very important to take that step.”

Statements showed that when the first police expert tried to read the fuzzy CCTV image, he couldn’t decipher it. However, he did render his opinion on what the foggy characters and numerals could and could not be. Later, he viewed the image again alongside suspect Bellfield’s vehicle’s license plate, however, and his conclusions then conflicted with those in his original statement.

“By presenting the forensic examiners with a ‘target’ license plate, their perception and judgment may have been affected and their conclusions biased,” Dror said. “Examiners should always first see the raw evidence and document their analysis in the absence of any potentially biasing information. And some information should never be presented to the examiners — information that is totally irrelevant to their analysis — whereas other relevant information should be presented, but only after their initial ‘context free’ examination of the evidence is documented.”

Citing a lack of precedent for a cognitive neuroscientist to testify on forensic decision making, the prosecution objected to Dror testifying. But the judge at London’s renowned court, the Old Bailey, let Dror tell a jury about the subjective way the brain perceives information based on context. “A very big legal precedent in the U.K.,” he said, with evident satisfaction.

He testified that having experts examine the CCTV image alongside the prime suspect’s license plate may have biased their conclusions.

The prosecution could have brought in their cognitive psychology expert to counter Dror. They declined, he said, “because they didn’t have anyone. Because what I say is basic psychology. There isn’t a psychologist on this planet or on any other planet who can come and say that judgment and perception are objective. It’s one of the most basic cornerstones of psychology. We can argue about when it happens, when it doesn’t happen, how strong it is, but the existence of confirmation bias and the issues I raised, which were totally new to the court, so totally new to the forensic domain, nobody can dispute.”

There was much other evidence against Bellfield, who was convicted. Dror was happy about that, but he also was happy to have been able to make his point.

He favors the immediate implementation of the practice of withholding all nonessential crime details from forensic scientists. Detectives, investigators, lawyers, judge and jury need to know if fingerprints are related to terrorism or bicycle theft, but for fingerprint examiners counting ridge characteristics, loops, whorls and other minutiae, such context is irrelevant.

“We’re not going to send a fingerprint to Interpol if somebody stole a bike,” Dror said. “But we need to make sure the fact that the examiner thinks it’s a terrorist or the Madrid bomber doesn’t cloud their judgment too much.” To Dror, it’s like his personal physician needing his medical history, while the lab technician counting his white blood cells for a blood test does not.

There are legitimate exceptions, he acknowledged. Genuinely relevant details might include, for instance, learning that a latent print was lifted from a knife or a vehicle steering wheel, which could convey important information about the degree of pressure likely exerted. Pressure can distort prints, as can various surface materials.

The many professionals Dror trains in methodologies to help protect their work from bias include U.K. fingerprint experts at forward-looking police departments like the Greater Manchester Police and the Hampshire Constabulary. With few exceptions, though, neither the U.K. nor the U.S. trains fingerprint examiners and other forensic experts to cope with and minimize bias.

Now the NAS report has opened a window of opportunity. Dror hopes that he will soon receive funding to start on more research. Meanwhile, he hopes that forensic scientists will at least stop claiming 100 percent accuracy and 100 percent objectivity.

“It’s not that they’re doing a bad job now,” he said. “It’s not that all their findings are incorrect. But in some cases, they are susceptible to error because of bias. And in all cases, they overstate the scientific validity of what they’re doing.”