The morning was clear and cold, with frost on the church steeple and the cemetery grass. I had a quick English breakfast at a white-cloth table, in my wetsuit, and drove to Newnham, a village on the Severn River in Gloucestershire, parking near the White Hart Inn. Glinting brown water stretched at least a hundred yards from the inn to cow pastures on the opposite side. The current moved with a placid, lazy force to my right. Across the road behind me, a pasture of sheep freezing their tails off bleated from different hapless positions on the grass.

“It’s a very slow wave,” an old farmer named Bill Bailey had told me in Cornwall, several hours to the south. “Just watch out for dead sheep.”

I blinked.

“Dead sheep?”

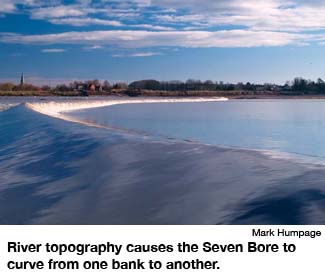

Bailey was among the first people ever to surf the so-called Severn Bore, a tidal surge of water up the Severn River that sometimes builds into a rideable wave. “When the river rises,” he explained, “it washes everything off the bank. Funnily enough, that’s where the wave breaks, by the bank, not in the middle, and one of these guys (in 1964) rode quite a long way. But in the end he got swept up on a bank. Then he was on a farm. He had to run across a pasture, and the bullocks chased him.”

Bailey is one of the nation’s surf pioneers, in saltwater and in fresh. In the mid-’60s he also co-founded Bilbo, Britain’s first surfboard company. Now he’s an old man — pouchy, bald, with bifocals, prone to wearing ill-fitting jeans and flannel shirts — but he may live to see the end of the unusual Severn wave.

“It’s gonna be stopped when they put the turbines in,” said his son, who was in the room with us. He meant a dam with turbines to harness the river’s power. “They say they’ll do the environmental studies, but they’ll have to do it — just economically. They say it’ll provide 4 percent of the power for the country.”

I climbed down the high bank at Newnham on a wrought-iron ladder that had obviously not been installed for surfers. I launched my board from a mossy rock and let the current glide me downriver. Half a mile in that direction, a line of surfers in colorful wetsuits waited in the waist-high water.

People watched in keen anticipation from the parking lot, now about 30 feet above the river, at the top of a stained concrete bank that resembled the hull of a battleship. It was a formidable work of flood protection, pocked with rusted drainage valves in case the river slopped over the edge and threatened the inn. A line of damp green scum showed where the tidal surge had flowed the night before — about a third of the way up.

Waiting for the Severn Bore can be nerve-wracking. I had no idea what to expect. I stood in the river, shifting my weight in the slick fine mud. The morning was calm, but there was something deceptive about the quiet. Soon a head of rushing whitewater marched into view. I heard hoots, and the whole line of surfers — with a few exceptions — began to move. Like a single creature, they combed upriver. The surge advanced with a steady, streaming, ineluctable rush. By the time it reached me, most of the wave was mushy and broken, only 2 feet high, but I managed to paddle in front of a glassy rolling section and take off. Then I was standing among 20 other surfers, old and young, plus a number of kayaks.

“All right, mate,” one of them said and made room. The bore is a limited resource, and no one feels possessive. People adjust their boards to new arrivals and keep moving, achieving a level of camaraderie I’ve never seen among surfers in such crowded conditions. We cut back and forth. We trimmed. We tried not to get caught in eddies or whirlpools or other spots where the stately, steady push of water might give out. The power of a wave like this would be determined not just by rocks and contours on the bottom of the river but also by the curve of banks and the power of the opposing current. People dropped away; others arrived. Soon I hit an eddy and fell. At first I was in denial — I thought I could catch another wave. A few swells followed behind the head of the bore, and I paddled after them. But nothing was really there except a high, rising, soupy volume of water. The wave comes — at most — once every 12 hours.

The whole river had changed direction. Instead of a placid flow to the right, from the parking lot’s point of view, it was now moving insistently to the left. I paddled to the bank and landed on a set of slippery, slowly disappearing rocks. I had to grab long reeds to climb up. At the top of the bank waited a man with a cup of coffee and a white beard who owned the property I was about to cross.

“Y’all right, then,” he said.

“Fine.”

“She moves fast.”

The Severn River is the largest waterway in Britain. It’s as important to the West Country and Wales as the Mississippi is to the American South. At low tide, from an airplane, its estuary is just a glistening expanse of rippled mud; but at high-tide seawater covers these mudflats and pushes upriver. The Severn narrows quickly enough to give the surges momentum, and when the tide is high enough, it creates not just a surfable wave, but also a current that changes the river’s flow for hours. Riverboat navigators know all about these surges. “With the aid of a good tide,” a retired Severn cargo skipper called B.A. Lane wrote in a 1993 memoir, “the time between Gloucester lock to the Upper Lode lock at Tewkesbury could be cut by at least an hour. No river man worth his salt would miss the opportunity of running with a good tide.”

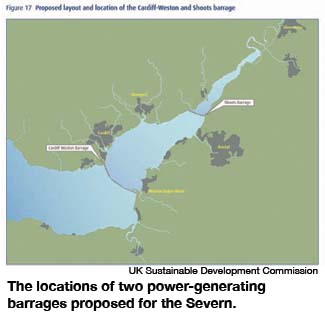

These tidal bores have given the British government an idea for a power-generation project that could match the output of four nuclear plants over its lifespan. The U.K.’s Sustainable Development Commission is considering proposals for a series of hydroelectric turbines — a “barrage” of underwater propellers — that in the most optimistic plan would gin up a maximum of 8.64 gigawatts of power, with no greenhouse emissions, for 120 years, humming along twice a day as an ideal renewable resource. The barrage would be “a comparable big infrastructure project” to the Three Gorges Dam in China or the Hoover Dam in the United States, says Bernard Bulkin, commissioner for climate change, energy and transport at the Sustainable Development Commission.

And it would kill the surfing wave.

America’s only tidal bore, called a burro in Spanish, once hassled steamboats on the Colorado River until the Hoover Dam slowed the river in the 1930s. Now, the Colorado peters out before it reaches the Sea of Cortez, and a tidal surge just floods salt flats in northern Mexico.

British surfers, unsurprisingly, are against a barrage, even though it will be different from the Hoover Dam. “The pointless and emotive sacrifice of a fully functioning river system to the gods of climate change is a misguided indulgent ‘green’ luxury,” says Stu Ballard, a bore surfer who runs a nonprofit called Save Our Severn. He worries that a rush by the government to build the barrage, driven by European Union carbon-reduction goals and a few special interests, will lead Great Britain down a byway explored by Canada decades ago. “For the Canadians,” says Simon Haslett, a professor at the University of Wales, Newport, “the idea of a barrage is now history and doesn’t even get raised as an option during tidal power debates. It’s so old that they are amazed the U.K. is even considering it.”

Of course, the British public doesn’t have much use for any “save the bore” movement based on a surfing wave, but most environmental groups agree with the surfers, and surfers have mounted the most interesting resistance.

“Initially I was out of step with the rest of the bore riders,” said Neil Law, a charity worker in Worcestershire who bodyboards the Severn and has submitted a report on the problem of silt to a government call for information. “I was prepared to contemplate the death of the bore if a viable means of generating renewable energy could be discovered.” He’d still be prepared to contemplate the end of the wave, he said, if the tidal flow were truly renewable. But he’s now afraid the barrage will destroy the current itself, robbing not just surfers of their waves but Great Britain of its 120 years of emissionless, guilt-free power.

The barrage will be a dam, a concrete barrier perforated with sluices and locks to let the tide push upriver, combined with a system of up to 300 underwater turbines built to spin on every falling tide. It’s not a new idea. An engineer named Thomas Fulljames first proposed a mile-long masonry barrage across the Severn in 1849, and other plans surfaced in the 1920s and 1970s, only to be rejected because of the cost.

But in late 2007, the British government formally started to investigate plans for a massive, maximum-power barrage. The idea is to squeeze every drop of low-carbon energy out of the river and weigh that potential against inevitable damage to the environment. There are several plans on the drawing board, but any major dam across the Severn would become one of the largest public-works projects in the world. John Hutton, Britain’s business and enterprise secretary, called the idea “a truly visionary project, unparalleled in scale. … The government Gordon Brown leads will not be among those who say they want to tackle global warming by moving to low-carbon energy sources but then oppose every opportunity to do so.”

One reason for the government’s new interest is, of course, global warming. Every nation in the European Union has pledged to reduce emissions by 20 percent before the year 2020, an impractical but catchy-sounding idea. A Severn barrage would make it far easier for the U.K. to meet this goal.

The other reason is oil. North Sea oil fields won’t last forever, and the government’s study of a tidal barrage admits that the U.K.’s expansive oil and gas industry “is in long-term decline.” So Britain needs to find a new source of homegrown energy, and resistance to a French solution — loads of new nuclear plants — is strong.

The government is seriously considering a short list of five tidal-energy proposals, all involving dam-like barriers that risk a problem with silt. The two most prominent are 1) the “Cardiff-Weston” barrage, a 10-mile dam with 200 to 300 turbines and a long causeway for cars along the top, connecting western England with Wales, and 2) the “Shoots” dam, farther upriver, with about 30 turbines and a fraction of the output (1.05 gigawatts instead of 8.64) but crossed by a high-speed rail link.

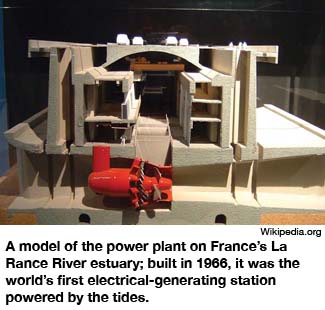

Barrage supporters point to a French dam, in the Rance estuary near Mont St.-Michel, which qualifies as the oldest and most successful tidal barrage in the world. It was built in 1966 and has run for decades without a significant problem. It has 24 turbines with a total capacity of 240 megawatts. Some detractors point to the Petitcodiac River in Canada, which receives a huge tidal bore from the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia. The Petitcodiac River Causeway, built in the mid-’60s as a crossing for cars and a flood-control system, has backed up the river with a surprising amount of silt, according to Stuart Ballard. “Within 15 years the whole river silted up,” he said. “They lost the capacity of the head pond to handle whatever floodwater was coming down. It’s not a barrage, but it’s the same principle. And now the Canadian government has agreed to take that out and replace it with a bridge.”

The only other commercial-sized barrage in the world, the Annapolis Royal Generating Station in Nova Scotia, also draws power from tides on the Bay of Fundy. It was installed in 1984 and still performs. But silt and erosion have reduced the river’s flow and made it less than an ideal model for a Severn barrage. The British government’s report on “Tidal Power in the U.K.,” which studies ideas for a barrage as well as other schemes, mentions the Annapolis station exactly once.

The trouble with silt is simple. Moving water keeps it afloat. If you let a huge volume of water through a dam and hold it for six hours, until the tide changes direction, you create a massive “head pond,” twice a day, which lets particles settle out.

“The people who are pro-barrage are saying ‘Look at La Rance, that works,'” Ballard said. “La Rance works, but it’s on a tiny scale compared to what’s being proposed here, and it’s in a steep-sided granite estuary, so the water coming through is crystal clear. And even so, they have problems with siltation. They have to dredge that.”

Although water in the Severn is a muddy greenish brown, silt has not been the focus of debate in Britain. Most domestic journalism on the project has focused on wildlife or on fiscal and carbon trade-offs. The long Cardiff-to-Weston dam would cost £15 billion to £20 billion (or $21.4 billion to $28.6 billion) to build, which is the cost to construct three or four nuclear power plants. And the savings in emissions would have to be balanced against the exhaust from trucks and machinery used to build the dam. So will it really save money or be “green?” These are the riddles British partisans in the barrage debate worry about, along with arguments over permanent damage to salmon, shipping, birds, eels and the delicate landscape of the Severn Estuary, which is protected by a number of British and European conservation laws.

The loss of a major estuary environment would, of course, be huge. The Severn’s salt marshes host endangered worms and migratory birds. Salmon swim up it to breed. So do eels; and European eels in particular have caught the public’s imagination because the larvae drift on currents across the Atlantic from the Sargasso Sea, near the Caribbean. Young eels, or “elvers,” swim with tidal bores up the Severn, and fishermen along the river have caught them, for centuries, in fine nets. The tiny wriggling clear young eels can fetch up to £150 per kilogram on a market that sells them to Japan, where they’re eaten as a delicacy. A dam with a barrage would kill or mangle a huge number of elvers even if some plans use turbines that could “minimize” the loss.

But these loss-of-species arguments involve a familiar cast of characters — people who worry about small animals, and people who shout them down. Climate change in this case is a trump card. If the world overheats, there may be no small animals to worry about. Malcolm Wicks, the U.K.’s energy minister, took this line in 2007 to criticize the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and its resistance to the barrage on behalf of “thousands of birds, spawning salmon and other fish.” Wicks told a committee of the Welsh parliament that the RSPB was “clearly not understanding that unless we are prepared to take some courageous action on climate change, the devastation of species will be truly enormous.”

Ballard, though, thinks silt is the “elephant in the river” that everyone has chosen to ignore. “They’re saying a barrage will last 120 years,” he said. “Now, is that 120 years before the estuary completely clogs up and becomes a mire and the last milli-amp is squeezed out from the last trickle of water? The point is, if a barrage is built, and then whoever’s building it agrees that it will have a finite life — can that be called renewable energy?”

The highway along the northern bank of the Severn is narrow and winds along green pastureland and the occasional stone-church village. The Severn Bore Inn, at Minsterworth, is a tavern with high-gabled farmhouse walls and brass lettering. I parked in a muddy yard at the rear of the inn, pulled on my neoprene boots and gloves, unstrapped the board and tromped across the frosted grass.

The inn itself hadn’t opened, but soon whole vans of surfers unloaded in the lot. They wore wetsuits and boots. A few had soft, white, numbered helmets. One of these men stepped over a sodden fence to the river.

I said, “Is there a race?”

“Hey? No.” He laughed.

I pointed to my head to indicate his helmet. “Just keeping track of yourselves.”

“That’s right.”

They turned out to be members of a bore-riding club. They wore helmets to distinguish each other in videos.

I followed a muddy path along the top of the bank, beside the sprouting green tips of trees growing from the waterline. Here the bank was an overgrown cliff. I looked for a way down until I saw a man I recognized from the previous night at the inn. He was a large guy with youthful but graying hair, a neck swelling with middle-aged fat and a habit of putting what looked like a plastic cigarette filter in his mouth, as if he wanted to light a cigarette. But after a few minutes, the filter went back in his pocket. He talked knowledgeably about the bore, and he turned out to be Neil Law. He was holding a digital camera.

He pointed to a slick, narrow muddy chute running down to the water. The bank here was maybe 15 feet high.

“Forget your dignity,” he said. “Everyone slides.”

I shrugged and took two steps down the chute, stepping on slick weeds, then I lost my balance and slipped on my butt straight into the water. There was a graceless splash.

A handful of surfers congregated just downstream at a wide bend in the river. It was shallow enough to stand, but the mud under our boots had a slick oily feel. The river had green, thickly hedged banks on both sides, with trees overhanging the water. A few surfers in numbered helmets discussed whether the wave would hold its power around the bend. One or two others were new on the bore.

“Wipe the mud off your feet,” someone said as he laid flat on his board to paddle. “Slippery.”

One surfer named Paul floated downstream as far as the elbow of the river, then stood and waited. The sun shone over the damp grass and trees. Sheep were bleating in the distance.

From the pasture smells near the river I assumed the slickness of the mud was due to sheep and cow shit, but that was wrong. Shit is biodegradable. What’s in the Severn, said Simon Haslett, the University of Wales professor, “is silt and clay from soil erosion. Twenty years’ worth of sediment is held in suspension in the Severn Estuary, which would all fall out and be deposited in a very short time after the barrage construction, and would then be added to annually.”

U.K. commissioners don’t have ready answers for this problem. “There is a study in progress on siltation,” said Bernard Bulkin, the commissioner for climate change at the SDC, who is otherwise well-versed on barrage economics. “It is a problem with dams, of course. Not all the silt problems of the Severn Estuary are well understood. My understanding is that the engineering view at the moment is that silt would be more of a problem for the Shoots barrage, or the smaller upstream barrages, rather than for the big barrage downstream. I’m not really the geo-technical expert who can comment on that … but the view is that silt is not as big a problem further down.”

He said a 120-year lifespan was the basis for all the government’s calculations, including the number of nuclear power plants a barrage might replace. (Two nuclear plants, lasting about 60 years each, replaced once, equals four.) “That just says we don’t know how long the lifetime is, but 120 years at least,” Bulkin said. “And how we do the economics of something like that is an interesting question — how do you value long-lived infrastructure? That’s one of the things the government is wrestling with. It’s very pointed in the U.K., because we have infrastructure built by the Victorians which is still serving us very well.”

But where did the 120-year estimate come from?

“Well, what we do know is that the one big barrage that’s in operation at La Rance has been going for 40 years. It has routine maintenance done on the turbines, and so on, but it shows no sign of any decay. So there’s no reason, based on that experience, to believe it would — you know, they use 120 years as their estimate.”

So the 120-year assumption for the Severn barrage was derived from La Rance, which operates on a granite riverbed?

“Yes, it’s drawn from their experience,” Bulkin said.

“But the difference between the Severn and the Rance is that the Severn really is full of silt.”

“Oh yeah. Absolutely,” Bulkin said. “But these are geo-technical issues … I think people who have studied this don’t believe any of this is insurmountable. These are just things that have to be dealt with.”

But Ballard argues that the barrage schemes made public so far don’t consider the silt problem in any responsible way. He says the science used by the government to estimate deposit problems is already outdated. Dr. Graham Daborn, a Canadian expert on estuaries, has studied silt in the Petitcodiac to figure out why the causeway had failed so quickly. He found that the studies treated each particle of silt as a “non-adhesive grain,” like a grain of sand. But silt in the Severn is sticky, and models of silt deposits haven’t been updated.

“People are going, ‘Yeah we’ll solve it.’ But they’re not actually saying, ‘What if we can’t?'” Ballard said.

One thing he and Bulkin agree on is that the U.K. should make more use of something called “tidal-stream” technology, which involves individual turbines on the bed of a river like the Severn or on the ocean floor. Tidal-stream turbines are free-standing. “One way of looking at them is that they’re like wind turbines, but capturing the energy of the flowing tide,” Bulkin said. “And the U.K., because it has a big coastline, has a tremendous tidal stream resource.”

Ballard would like to see tidal-stream turbines used instead of a barrage or any dam-like barrier. The turbines — which can be swapped out as technology advances — are more flexible than 10 miles of poured concrete. The difference from the government’s point of view is that no single system of free-standing turbines will gin up as much energy as a single barrage, so no single “tidal stream” project has numbers impressive enough for a bureaucracy to peddle as a solution to a major climate change deadline.

“What I’m saying with Save Our Severn is, ‘Let’s do something better with the river,'” Ballard said, “‘Let’s leave it a future, not just sacrifice it to short-term policy like this 2020 (European Union) directive.'”

At the Severn Bore Inn, after the wave, the parking lot filled with about two dozen dripping, shivering river surfers, a possibly endangered species in Britain. Neil Law arrived with his camera, and we stood around to watch the replay, which included a group of men in silly numbered helmets.

“Somebody passed a fridge-freezer above Newnham,” one surfer said.

“Oh, so that’s where it is,” Law said.

“Moves up and down, does it?” someone else asked.

“Yeah, every bore someone has a fridge-freezer sighting. It’s been floating up and down for at least two years. Allegedly,” he said. “Allegedly, somebody even rode it one year. He said he fell off his board and found this fridge-freezer floating next to him, so he climbed on it and rode it some way like a bodyboard. Allegedly.”

I took this opportunity to mention dead sheep. At the very least, I thought, a concrete dam across the Severn might save a number of farm animals.

“Oh,” Law said, shrugging. “I’ve heard that about sheep, too. But I’ve been following the bore for years, and I’ve never seen any dead livestock.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.