The aviation industry and its regulators will be lobbying hard next week at COP24 in Poland to sell the world on a global carbon market to offset airlines’ rising emissions. There, negotiators will be working toward standards for emissions reduction credits, which could make or break the industry’s scheme to offset its growing carbon footprint—a stopgap measure while the sector explores technologies and pathways to full decarbonization, including electric flight.

Electric aviation, long stymied by the limitations of battery technology, is finally taking off: Battery-powered air taxis, passenger drones, autonomous aircraft, and even passenger planes are all under development by aerospace and aviation companies around the globe.

The change could not come soon enough for an industry that has largely avoided responsibility for reducing greenhouse gas emissions while the rest of the world clamps down on carbon. Aviation accounts for about 4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and its share of the carbon budget is only expected to grow. That means replacing gas-guzzling planes with electric ones could put a real dent in global emissions—heartening news in the wake of the latest findings from the United Nation’s top climate panel, estimating that the world has just over a decade to drastically reduce emission and prevent the most brutal long-term effects of climate change.

Electrifying aircraft isn’t just good for the planet, but for airlines and passengers as well: Given the hefty price tag of jet fuel, electric flights will eventually be cheaper than those powered by fossil fuels. Electric engines require less maintenance and are quieter than conventional ones, which could open up new routes for flights that are currently off-limits because of noise restrictions. And electric engines are safer than conventional ones, according to Donald Hillebrand, the director of Argonne National Laboratory’s Energy Systems Division.

“Flying is shockingly safe: The odds of something happening are very low, such that it becomes a headline when it happens, but when you go to electrification there are even fewer moving parts,” Hillebrand says. “Pilots would feel much more comfortable having an electric motor on the front of their aircraft than having a gasoline motor, because you can really reliably understand what an electric motor is going to do.”

So why aren’t the skies full of electric airplanes already?

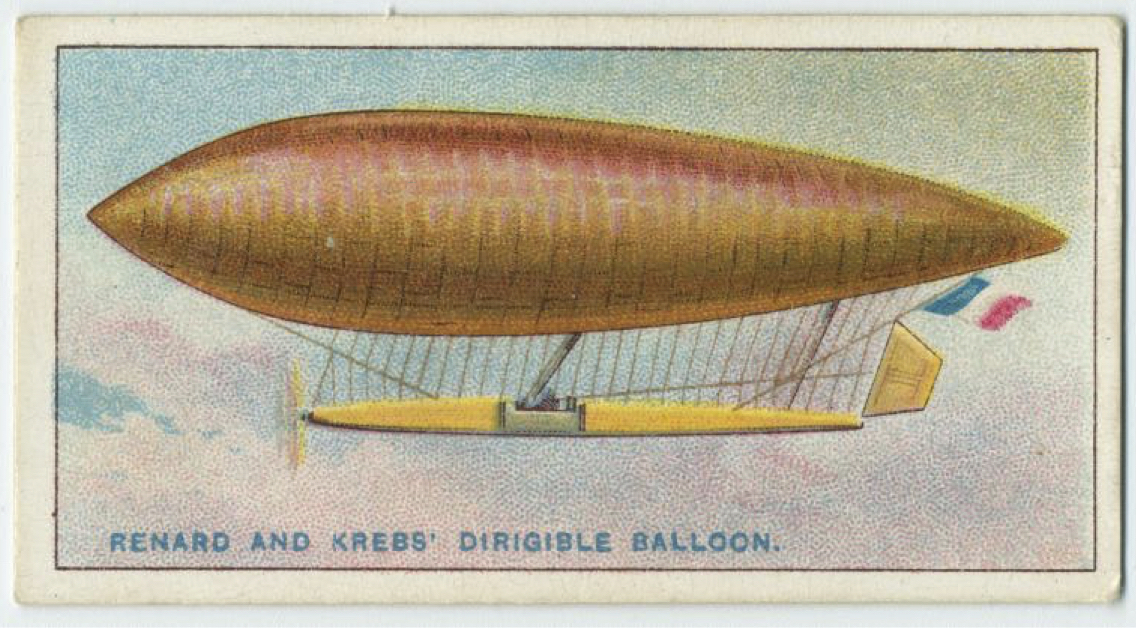

(Photo: New York Public Library)

Electric flight is nothing new: As far back as the late 19th century, french engineers were adding batteries and electric motors to dirigible balloons. Almost a century later, solar-powered, unmanned airplanes began setting records for fuel-less flights. But electrifying passenger planes in particular is a feat of engineering that has proven much harder than electric flight in itself.

Investment in electric aviation today tends to fall into one of two categories. The first is air taxis that enable short flights (think a cross-town ride in a city), such as Uber’s four-passenger, vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft, Dubai’s two-seater air taxi, Kitty Hawk’s autonomous taxi plane, or SureFly’s two-person octocopter drone. Electric air taxis and personal helicopters are objectively cool, but they’re unlikely to make a significant dent in aviation’s emissions.

The second area of investment is hybrid planes, which use both electric and gas power, for longer but still regional flights. Hybrid planes are a logical first step, according to Hillebrand, because though battery capacity has been increasing by about 5 percent every year, it’s still nowhere near ready for longer flights.

“Batteries are improving, but to really get to the point where batteries are fully capable of carrying aircraft around for hours, that’s far out in the future,” he says. “To start planning for it now, you have to look at how you work with batteries that aren’t as capable, and combine them with engines.”

The aviation industry is always designing around the promise of future technologies, according to Hillebrand. Massive airliners like the Boeing 747 were designed in the 1950s, he notes, but those in the air today have modern navigation and communication technologies. As batteries improve going forward, fuel can be phased out more and more.

How One American Company Is Preparing for the Revolution

Aviation accounts for some 12 percent of transportation-related emissions in the United States, and the downside to hybrids is that they still produce pollution, according to Roei Ganzarski, chief executive officer of MagniX, an electric propulsion start-up. “The only way to eliminate emissions is to go all-electric,” he says. “You could say that a Toyota Prius produces a lot less emissions than a regular car—that’s true—but it still produces emissions.” Ganzarski believes short-haul flights can be all-electric sooner rather than later.

MagniX’s approach is to build an electric motor for standard aircrafts that fly nine to 15 passengers on standard, 100- to 1,000-mile routes, and that take off and land at standard airports. “So the only thing that’s different is, instead of being gas-guzzling, emissions-creating aircraft,” he says, “they don’t need any fuel and don’t create any emissions.”

Earlier this fall, MagniX passed a critical milestone: powering a propeller on a Cessna “Iron Bird” with the company’s 350-horsepower, all-electric motor powered exclusively by battery. Right now, that aircraft is still firmly on the ground, inside one of MagniX’s engineering facilities in Australia. MagniX plans to conduct hundreds if not thousands of hours of tests on its motors, then get a flyable aircraft out of the warehouse and onto the runway, to see how the motors perform on a taxiing plane, followed by the first test flights to take place within a year.

Ganzarski hopes to work with airlines shuttling people on short trips around the country: to the San Juan Islands, the Hamptons, or the Florida Keys, to name just a few such routes. Around 30 percent of flights in the U.S. are less than 500 miles in range, according to Ganzarski. “There are thousands of these aircraft flying around, using a lot of fuel, and creating a ton of emissions by flying people very short routes,” he says. “Our goal is to go to these operators and say, ‘Hey, why don’t you convert your aircraft to an all electric.'”

Of course, there are many regulatory and technological hurdles to cross before we’ll start to see these electric aircraft take to the skies—chief among them, range. While batteries have improved, they still can’t get aircraft as far as fuel can, and they take longer to recharge than it takes to refuel. Right now, for every hour of flight, an aircraft’s battery would have to charge for at least an hour. That’s why MagniX is focusing on aircraft that don’t need to turn around and take off quickly; these include not just small passenger planes, but cargo planes as well, which often spend a few hours on the ground unloading and reloading cargo.

Eventually, MagniX’s goal is to scale up to big, commercial airliners carrying hundreds of passengers at a time. “Just like with cars, you start with a Tesla with two passengers, then you go to a four-passenger car, then you go to a six-passenger SUV, and now suddenly you’re going to buses,” Ganzarski says. “It’ll be the same thing with aircraft.”

Not everyone agrees: “The manufactures have jumped onto the battery bandwagon because that’s what happened in road transport,” says Bill Hemmings, the director of aviation and shipping at the environmental organization Transport & Environment. But, he says, there’s no way that battery electric power could replace long-haul or medium-haul flights with electric aircraft anytime soon—”and that’s where the bulk of emissions are.”

“I’m one of those skeptics who thinks that we’ll never actually get a battery that’s so efficient and so energy-dense that you’ll be able to actually fly more than regionally,” Hillebrand says, but he notes that major manufacturers like Boeing and Airbus are studying batteries for long-haul flights, and keeping the results under wraps, which suggests that, for now, the corporations still believe it’s possible and want to keep an edge over their competitors.

“It seems so impossible, but then again, five years ago we were talking about electrifying heavy-duty trucks and we all thought that was funny. It was something of a joke,” Hillebrand says. “They’re driving on the road right now, so it shows how quickly those attitudes can change.”

Electric 747-size airliners may still be still decades off, if they ever arrive at all, but Ganzarski believes that government-mandated targets for electric flights could help get us there faster. “Why not put a line in the sand that says, ‘By 2030 or 2040, X percent of interstate flights should be electric’? There’s no reason we shouldn’t do that,” he says. “As long as the policy isn’t there, the industry says, ‘I’ll take my time and hedge my bets.'”

Such policies already exist in some countries: Norway, for example, which is already the world’s top buyer of electric cars, is now mandating that all domestic flights be electric by 2040. “Norway’s led the way for the electrification of the automobile and the electrification of their economy,” says Hillebrand, noting that there are several reasons why the Nordic country is leading the way on electric aviation too. “It’s an extremely wealthy country, because of their oil revenue—as ironic as that seems—but also the actual geography of Norway,” he says. “The deep fjords, which are too wide to bridge, require massive distances to drive … so the Norwegians are very interested in developing electric aircraft that will make the hops over the mouths of the fjords.” The first passenger flights are expected to begin in Norway by 2025, and the country’s transport minister, Ketil Solvik-Olsen, has already taken a spin around the Oslo airport in an electric plane built by the Slovenia-based company Pipistrel.

But for now, flying is still a carbon-intensive form of travel. Just one flight can wind up being a large portion of an individual’s carbon footprint: One round-trip flight to Europe, for example, can cause warming that’s equivalent to two to three tons of carbon dioxide emissions per person—that’s 15 percent of the average American’s annual emissions. The best way to prevent those emissions for now is to keep your feet on the ground.