This story was produced in collaboration with the Marshall Project. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

When Borey Ai walked out of prison after serving nearly 20 years for the murder of a woman during a robbery, he was stunned to see immigration agents waiting to take him into custody.

“I had all these aspirations,” Ai says. “I was shocked and devastated, and I felt that I was back in prison.”

Ai, who is now 37, was born in a Thai refugee camp before coming to the United States at age four. His parents had fled Cambodia’s brutal Khmer Rouge regime and were eventually resettled in California’s Central Valley.

Now, he faces deportation to a country that he doesn’t consider home.

Ai is one of about 20 Southeast Asian immigrants who are seeking pardons in the final weeks of Governor Jerry Brown‘s term, hoping for a grant of mercy that will allow them to stay in the U.S.

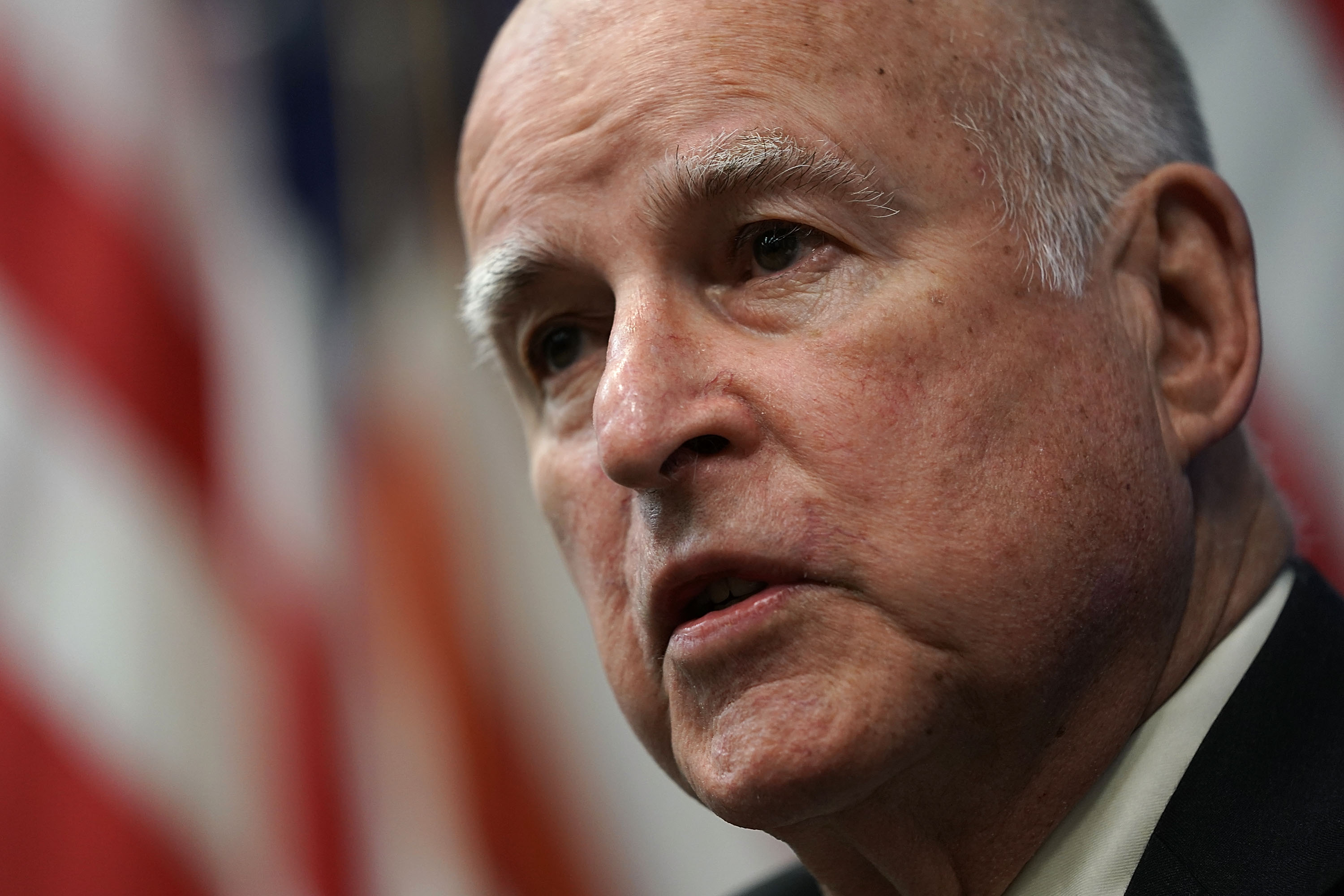

Unlike President Donald Trump, who has focused attention on cases brought to him by fellow celebrities and on political allies, Brown’s clemency decisions focus on people facing what the governor seems to view as systemic injustices. They are often timed to coincide with Catholic holidays, a reflection of his faith.

“It’s a recognition that people can, and do, change—even after committing terrible crimes,” Evan Westrup, a spokesman for Brown, said in a statement. “It’s also a recognition of the radical and unprecedented sentencing increases and prison building boom of the ’80s and beyond as well as the diminished role of parole as a vital ingredient in California’s system of sentencing and rehabilitative process.”

Among the people who have received clemency recently: Southeast Asian immigrants who came to the U.S. as children and who face deportation unless granted a pardon; non-citizen military veterans who were deported for crimes committed after their service; and prisoners serving life without parole, who were given hope of release.

“It really ties in with Brown’s attitude toward criminal justice,” says Anoop Prasad, an attorney who represents a group of Southeast Asian immigrants seeking pardons. “He realizes that California made major mistakes, and he was partly responsible and is trying to walk it back.”

During his first two terms in office, from 1975 to 1983, Brown oversaw a dramatic shift in sentencing policy that led to a surge in the state’s prison population and coincided with a number of tough-on-crime bills.

In those years, he handed down only one commutation and about 400 pardons. A commutation reduces the sentence of someone currently in prison. A pardon clears the record of someone who has served out a sentence.

By contrast, since returning to the governor’s office in 2011, Brown has issued 82 commutations and more than 1,100 pardons, far more than any California governor since at least the early 1940s.

The previous governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, issued only 10 commutations and 15 pardons during his two terms. His predecessor, Gray Davis, issued none.

Nationally, the number of pardons and commutations varies widely by state and does not easily break down among red states and blue states, according to professor Mark Osler, an expert on sentencing and clemency at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minnesota.

Several states, including Georgia and South Carolina, give clemency power to independent boards. Those states tend to have a more consistent number of pardons and commutations each year than states that give discretion to the governor, Osler says.

“If you leave clemency largely in the hands of one individual, then your outcomes are going to be different from one administration to the next,” he says.

Although Brown’s critics may not agree with his views on criminal justice, they say those views, not celebrity lobbying or political loyalty, appear to inform his clemency decisions.

“These appear to be motivated purely by his sincerely held beliefs about incarceration and punishment,” says Michele Hanisee, president of the union that represents Los Angeles County prosecutors and a frequent critic of Brown’s criminal justice policies. “While one may or may not agree with those, or who he is choosing, they’re not motivated by political cronyism. … His commutations and pardons are consistent with his known views on criminal justice.”

Ai, who is known as “Peejay,” is one of about 2,000 Cambodian immigrants throughout the country who are currently facing deportation. Prasad is working as part of a national campaign to assist Cambodians and other Southeast Asian immigrants from Laos and Vietnam whose communities have been targeted in recent immigration raids.

Many of those applying for pardons have never been to their home countries and say that, although they aren’t American citizens, they are culturally American. In Cambodia, the plight of deportees from the U.S. has been an issue for years, but immigration advocates say the pace of deportations has accelerated under the Trump administration.

In California’s governor, these immigrants hope they have found a politician who is sympathetic to their situation, even for some with serious criminal convictions, Prasad says.

“I think Brown has started to push the boundaries a little bit,” he says. “For a while, he pardoned only relatively minor and non-violent offenses.”

(Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Many of the immigrants’ life stories share common threads.

Ai’s parents witnessed the murders of their family members in Cambodia during Pol Pot’s reign. They escaped across the border into Thailand, where they lived in a camp with thousands of other refugees. That’s where Ai was born.

They eventually settled in Stockton, living among other Southeast Asian refugees in a community with few jobs, high poverty, and rampant crime. It was a hard place to begin a new life for his parents, he says, particularly because they were still traumatized from Cambodia.

“I grew up in dysfunction,” Ai says. “My parents were so traumatized. A new country, a new culture. I never had a childhood.”

He says he lost any sense of safety in 1989. Ai was a student in Stockton’s Cleveland Elementary when a gunman opened fire, killing five children and wounding more than 30 people. Many of those targeted were Cambodian refugee children, including Ai’s young cousin, who was killed.

As Ai got older, he fell in with gang members. At 14, he robbed a liquor store in San Jose. During the robbery, he shot the owner, 52-year-old Manijeh Eshaghoff in the neck, killing her.

He spent about 19 years in prison for the crime. During that time, Ai began volunteering and participating in programs aimed at rehabilitation. He trained as a counselor, learning tools to help others struggling with trauma and violence.

After the parole board granted him freedom, he was released from San Quentin State Prison in November of 2016.

“I had job offers, I had goals, people who I wanted to meet,” Ai says.

Instead, he spent 18 months in immigration detention. He applied for a pardon, hoping that Brown would wipe away his conviction and allow him to remain in the U.S.

In late October, Ai appeared before the full Board of Parole Hearings to make his case. So many supporters wanted to speak that the hearing room quickly filled, and people had to rotate in and out to speak on his behalf.

A prosecutor and family members of the murdered woman also spoke, opposing his release.

In an interview, Eshaghoff’s young brother, Moussa Moshfegh, 72, says he was angered by the support for Ai.

“If he’s pardoned, to us, it appears that this thing never happened,” Moshfegh says. “We are stuck with a life sentence of not having our sister.”

His sister was also an immigrant. An Iranian Jew, she fled the Iranian Revolution. She and her husband eventually settled in San Jose and ran a liquor store. A mother of three boys, she set up a kitchen in the back, cooking traditional Iranian food and fixing sandwiches for hungry children.

Her death devastated her family, and a pardon from the governor would deepen the pain, her brother says.

“We are forgiving people. It was tough to accept it, but I don’t mind him getting out,” Moshfegh says. “But being pardoned, as if it didn’t happen—I have no problem with him getting deported. He can be helpful there. Let him be deported. We all have to pay consequences.”

The parole board has approved Ai’s pardon application. His case now goes to the California Supreme Court and, if approved, to the governor. Brown has often announced clemency decisions just before Christmas, but migrant advocates are hopeful that he may make his decisions earlier this year, before more people are deported.

This piece was produced by the Marshall Project, a non-profit news organization that seeks to create and sustain a sense of national urgency about the U.S. criminal justice system.