On June 23rd, 2016, as I was writing After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, beginning the process now known as Brexit. The Leave Campaign that preceded the vote played on fear of immigrants, and the coalfields of south Wales supported Brexit by a narrow margin. Five months later, voters in the United States elected Donald Trump as president. Trump’s “Make America Great Again” campaign received strong support from voters in former coal mining and industrial regions, who were attracted by his promise to renegotiate international free trade deals in order to protect American workers and to crack down on illegal immigration. On both continents, fear of an uncertain future created support for isolationist policies. The unemployed blue-collar workers (including some laid off miners) who supported the Trump campaign or the Brexit vote felt that the global economic system had left them behind—and they were right.

Yet if we are to address legitimate concerns about workers who are left behind by a global economy, then shutting down borders and blaming foreigners is not a solution. We need to work across borders to develop systems of mutual support. In fact, closing borders can cut off important resources that have allowed communities to regenerate on their own terms. For example, several of the Welsh initiatives featured in the After Coal documentary, such as the DOVE Workshop and the Glyncorrwg Ponds and Mountain Bike Centre, have used funding from the European Union strategically to increase opportunities in the communities they serve.

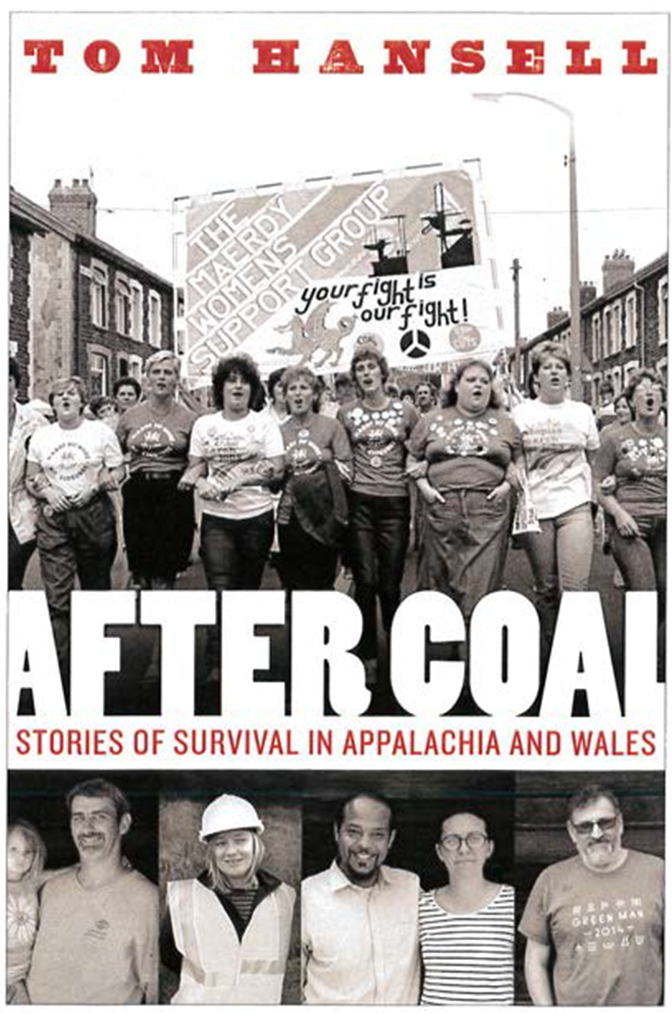

(Photo: West Virginia University Press)

In the Appalachian coalfields, fear of the federal government is often stronger than fears of foreign immigrants. Yet federal agencies such as the Department of Agriculture, the Economic Development Administration, and the Appalachian Regional Commission often play an important role by distributing resources to high-priority areas such as coalfield communities. For example, most local governments in Appalachia do not have the resources to protect their water sources. Often, local officials turn to federal programs such as the Abandoned Mine Lands fund to run water lines to rural residents, reclaim mine sites, and provide a foundation for sustainable development. Clearly, the government should play an important role in providing access to clean water, which is an important requirement for economic development.

In order to achieve a just and equitable transition from coal (and other fossil fuels), we need to develop global systems that do not leave working people behind—global systems that support local communities. These systems could be linked internationally, but in the words of Wendell Berry, they cannot “export local products until local needs have been met.” Berry astutely observes that scarcity of resources is a major cause of anger and political unrest. Meeting local needs is an essential step to create peace and prosperity. Developing international connections to support coalfield communities on a path to self-sufficiency is a key concept to create a future beyond fossil fuels.

Excerpted from After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales (West Virginia University Press, 2018). Used with the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.