On a hot night in April of 2014, hundreds of fighters with the jihadist group Boko Haram descended on the town of Chibok in northeastern Nigeria. As they had elsewhere in this impoverished region, the radical Islamist terrorists ransacked the town, torching buildings and raining gunfire down on residents. Unlike in previous raids, Boko Haram found a surprising opportunity awaiting them in Chibok: a boarding school full of teen girls, whose teachers and security staff had fled. Boko Haram means “Western education is a sin” in Hausa, the dominant language of the region. In a video from the time, Boko Haram’s then-sole leader, Abubakar Shekau, ranted: “Stop going to university, bastards! Women, go back to your homes!” That night, Shekau’s followers rounded up 276 students at the Government Girls’ Secondary School, many of whom had left their distant home villages to get an education, and drove the girls into the Sambisa Forest.

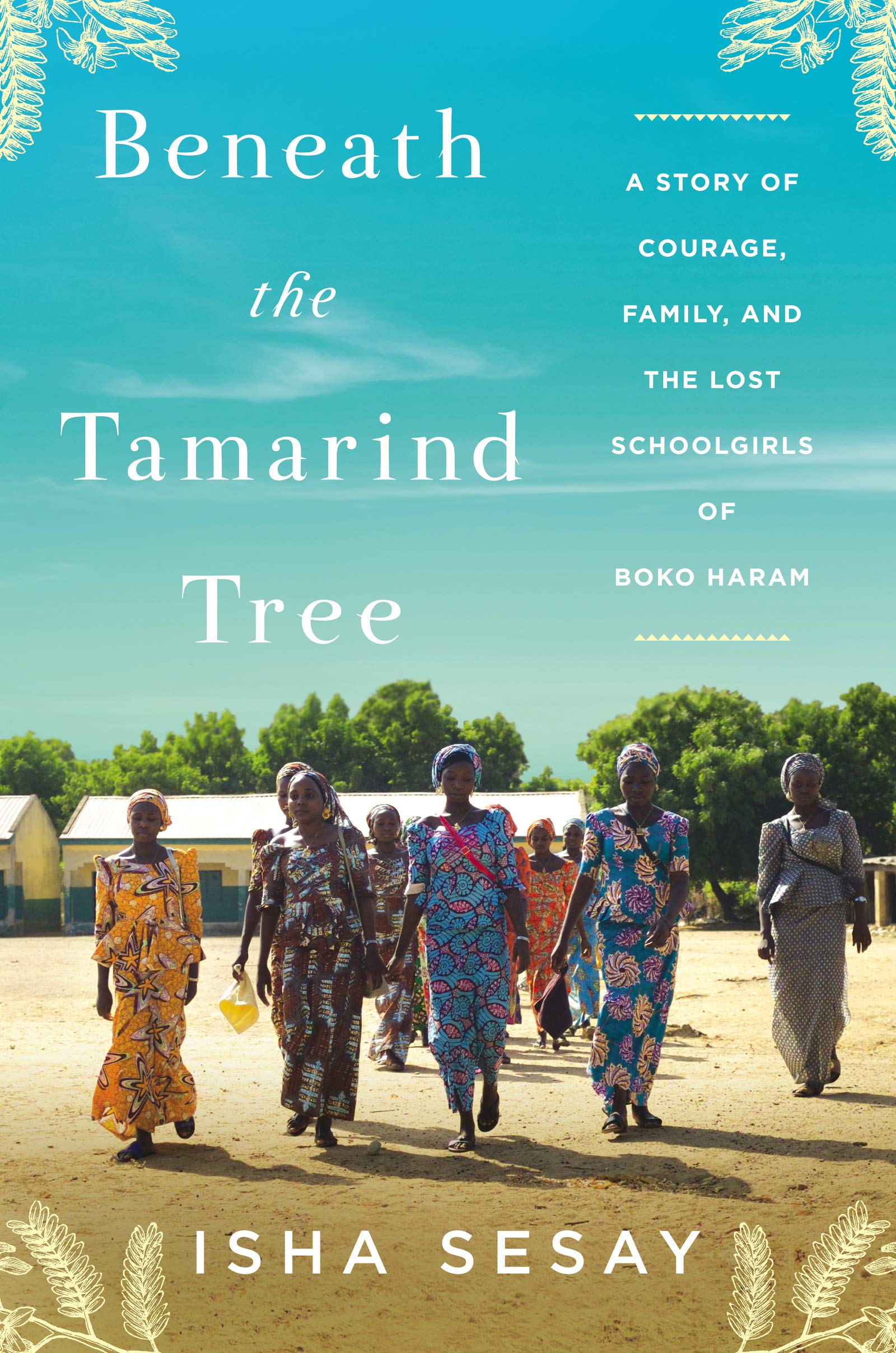

Isha Sesay’s Beneath the Tamarind Tree explores what happened next.

Many in the West began paying attention a few weeks later, when a social media campaign to bring attention to the girls’ plight began gaining steam. Then-First Lady Michelle Obama posted a photo of herself holding a #BringBackOurGirls sign, further raising the story’s profile. But then the attention faded, and today many people in the West know precious little about what exactly happened to the girls. In reporting Beneath the Tamarind Tree, journalist Isha Sesay managed to gather gripping details about the Chibok girls’ full, extraordinary story, from their journey through the dark forest, where some leapt from moving trucks to freedom; to the months the girls spent living outdoors under a large tree; to the pressure they faced to convert to Islam (most were Christian) and marry their captors; and, finally, to the return of some, but not all, of the girls to their families and school, more than two years later.

Boko Haram eventually traded a total of 103 of the girls for their own soldiers whom the Nigerian government had captured. One hundred and twelve girls—now young women—remain missing.

Beneath the Taramind Tree is a story about international politics and the status of women and girls worldwide. But it also has a surprising dash of drama and heroism, mostly provided by the Chibok girls themselves, who prove resourceful and resilient in the face of injustice and danger.

Sesay covered the girls’ story as a longtime anchor for CNN but left the network in May of 2018, in part because she felt that news in the United States had become too obsessed with the presidency of Donald Trump. “There were other stories I wanted to tell,” she says.

Sesay spoke with Pacific Standard via phone on Monday to discuss the Chibok students, and what their story can teach readers in the West.

What exactly did Boko Haram want with these girls?

Boko Haram had been abducting women and girls, in smaller numbers, over years. The norm had been to take them and use them as sex slaves, use them as human bombs, brainwash them, radicalize them. They’d been taking boys as well as girls.

But in the case of the Chibok girls, Shekau, who was the leader of what was then a unified Boko Haram, very quickly understood the value of his hostages. He knew he had something that was effectively a pawn in a wider game [to secure the release of Boko Haram members from the Nigerian government].

(Photo: HarperCollins)

These girls were kidnapped for daring to go to high school, basically. How much education do most girls in Nigeria get?

Northeastern Nigeria has one of the highest out-of-school population numbers in the entire world. The most recent numbers are something like between 8.5 and 10 million children [who] are out of school.

There’s a wide discrepancy between education and literacy between the north and the south [in Nigeria], and between men and women in the north. There was a survey done in the early 2000s: Only 4 percent of girls were graduated from secondary school, from high school, in the north.

The girl who manages to get to secondary school, manages to get a higher national diploma, will go on to university, start her own business, or become a teacher. She’ll take on some sort of professional role. But the majority of Nigerian girls are getting married before they’re 16, so that’s really the alternative.

How did this happen? How could hundreds of boarding-school students just vanish into the night for more than two years?

There were multiple failings. The school said: “If something happens, do not leave until a teacher comes, or else you’ll get in trouble,” which also explains why the girls didn’t run. It’s so distressing when I think about how they sat and waited, thinking someone would come, and someone did come, but it was the men who stole them.

The Nigerian government told the international media that, within hours, within days, they were on the ground, launching a search. I spoke with family members. They said that that wasn’t true. At least a week went by before they saw any sign of a government presence on the ground.

Why did it take so long to do a deal with Boko Haram?

I think a mixture of reasons. I think that the government was loath to do a deal with terrorists, which I think many governments will say is their position. I feel there was a sense this story would just die down. There wasn’t really an urgency to do a deal.

In the book, you criticize CNN for not airing more of your coverage of the first release of a group of 21 girls, in October of 2016. “Election fever had burned away interest in everything else,” you write.

(Photo: Cathrine White)

I was very disappointed. I was very hurt for the girls. I felt it deserved more than just a 10-second reader on CNN USA.

I did a few hits on CNN International, maybe two or three that evening. I honestly thought: “The world is going to be transfixed. These girls are out. This is amazing. This is a good news story out of Africa.” And it just didn’t gain traction.

Why do you think it’s important for American viewers to see more coverage of this story?

First of all, they would know what happened. I run into people now and they go: “Oh are [the girls] back? Did they get any of them?”

We’re supposed to see these stories through to the end, so people get a full understanding of what happened.

How are things in northeastern Nigeria now? Are families more afraid to send their girls to school?

Of course, and who could blame them? Boko Haram displaced some two million people in northeastern Nigeria. In recent weeks, they have stepped up their attacks. They are a menace.

Why would you send your children to school when the world moved on when there’s still 112 children missing? You can’t even blame them.

What are the released girls doing now?

Over 90 of them are in a school in northeastern Nigeria. They’re continuing their education. They want to be doctors and accountants. They are positive and forward-looking. They are unrelenting.

I think it’s a natural assumption to make, that when these girls were taken, they lost all agency. Their captors were threatening to kill them at every turn. But what I really take away is the acts of defiance they carried out in their time in captivity: refusing to marry or convert to Islam, or refusing to bathe. Just these small acts of defiance. Or continuing to practice their faith in private, even though their captors said, if they were caught worshipping as Christians, something terrible would happen to them.

The narrative about black girls, African girls, isn’t always about us as survivors. It is all victim-led. I hope that this books help shed a light on the expansiveness of African girls. They are strong. They are resilient.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.