In the autumn of 1980, a contractor showed up to grade a parking lot. He had no idea he was about to start digging up the radioactive bodies of dead beagles. But the forked bucket on his bulldozer started pulling up more than soil, and it turned out he was digging in a pit of strontium-90 and dog carcasses that had been buried in an ash-gray tomb: a nest of dead dogs and laboratory waste labeled “Radioactive Poison.”

The new parking lot was on the site of the former Naval Research Laboratory dump and its associated incinerator in Camp Lejeune, North Carolina—and it was just one of many areas contaminated by an assortment of hazardous waste and chemicals on the base.

About half a mile away from the dump, soon to be known as Site 19, my friends and I were living in our neighborhood, called Paradise Point. We spent our time putting other girls’ bras into freezers at slumber parties, playing the Telephone Game, riding our bikes all over the place: to the golf course to steal a cart, to swim at the pool, to play soccer on Saturdays.

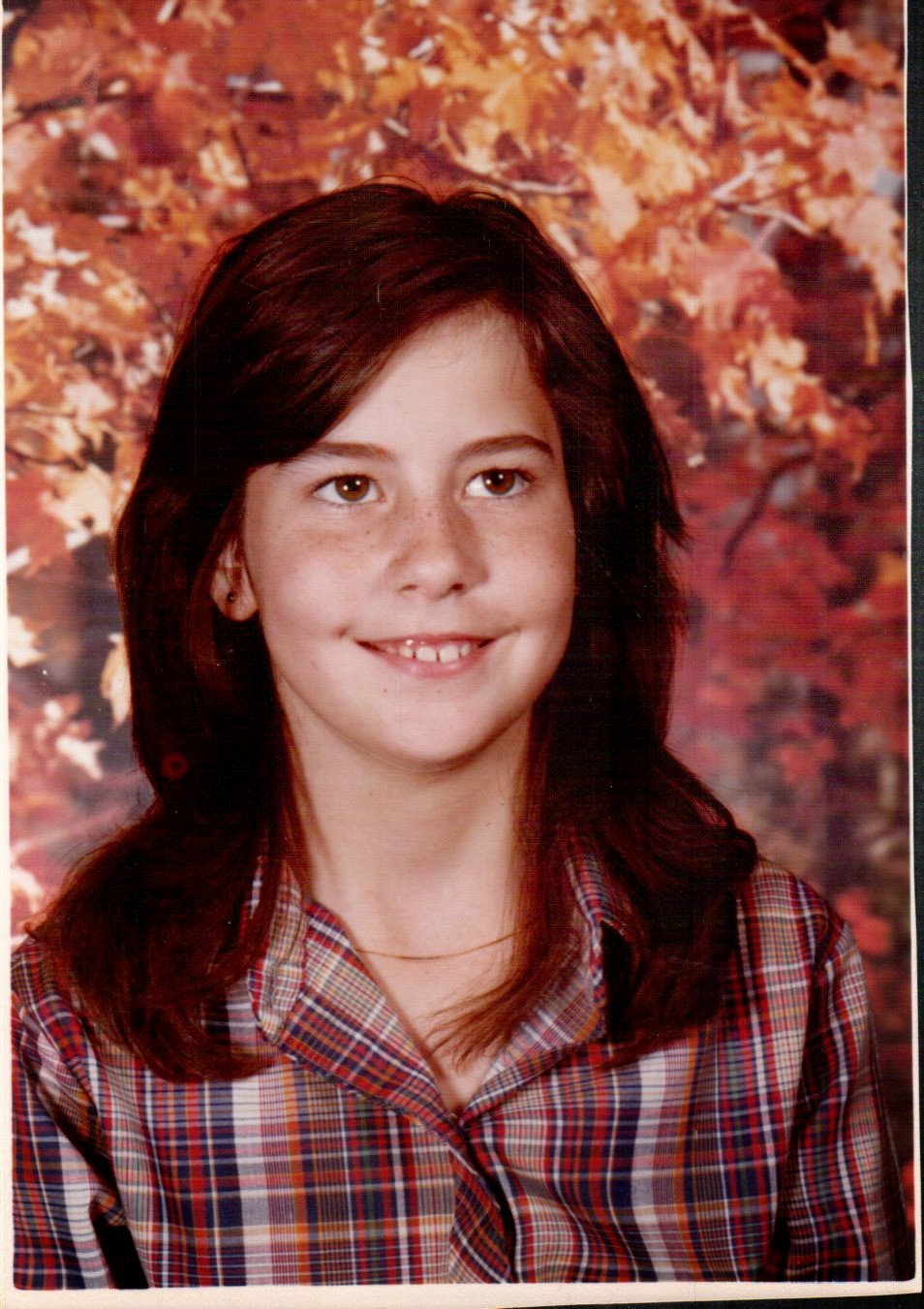

During the same autumn the dead beagles were found, I was sitting in front of a fake backdrop of rusty colored leaves, a slight 11-year-old girl with spaces between my teeth and freckles spritzed across my nose and cheeks, to take my school photo.

(Photo: Lori Lou Freshwater)

Under normal circumstances, this entirely unremarkable fifth-grade photo, in a plaid shirt and fragile gold necklace, would have likely ended up where most school photos do, in an old album or a drawer or simply lost to time. Instead, the photo would become a marker in the medical history of my family and my community, a reminder of the crime that was being committed on the day the photo was taken—and also for decades before, and for years after.

The place was Camp Lejeune, a United States Marine Corps base wrapped around the New River in Onslow County that served as an amphibious training base where Marines learned to be “the world’s best war fighters,” picking up skills that would allow them (for example) to make surprise landings on the shores of far away countries. From the 1950s until at least 1985, the drinking water was contaminated with toxic chemicals at levels 240 to 3400 times higher than what is permitted by safety standards.

There may never be a true accounting of the suffering caused at Lejeune. As with many other hometown environmental disasters, the Marines and family members poisoned on this military base were not born here, nor did they settle here to make a permanent life and raise their children. Instead, they were often here just for a short time, literally stationed at Lejeune for weeks, months, or, at most, a few years. From the 1950s through at least 1985, an undetermined number of of residents, including infants, children, and civilian workers and personnel, were exposed to trichloroethylene (TCE), tetrachloroethylene (PCE), vinyl chloride, and other contaminants in the drinking water at the Camp Lejeune. These exposures likely increased their risk of cancers, including renal cancer, multiple myeloma, leukemias, and more. It also likely increased their risk of adverse birth outcomes, along with other negative health effects. Now the sick and the dying are all over the world, and an untold number will never be notified about what happened. Instead, we are left to rely on scientific models and data trickling out of public-health agencies and the slow process of adding one story at a time, person-by-person, to the cold data representing an environmental and public-health disaster.

In 1989, the Environmental Protection Agency placed 236 square miles of North Carolina’s coastal soil and water on the list of toxic areas known as Superfund sites. The agency cited “contaminated groundwater, sediment, soil and surface water resulting from base operations and waste handling practices” as reasons for including it on the National Priorities List.

Camp Lejeune remains a sprawling Superfund site, and it is also the place where my mom and I spent years drinking a terrible mix of chemicals from our faucet. In the book A Trust Betrayed: The Untold Story of Camp Lejeune, author Mike Magner gives special attention to my mother’s story: “A woman with the ironic name of Mary Freshwater may have had the most ghastly experiences at Camp Lejeune.”

Of course, I share her ironic name, which can still seem like more of a curse. Nearly my entire childhood was consumed by tragedy. The chemical contamination can be linked to the deaths of my two baby brothers, Rusty and Charlie, and to my mom’s own difficult final years, when she was dying from two types of acute leukemia. My mother also suffered from mental illness, which was intensified—understandably—by our family’s brutal losses. Sometimes it seems that, behind me, there is nothing but inescapable grief.

My middle school was called Tarawa Terrace II, named for the famous World War II Battle of Tarawa. I rode a Marine-green bus every day instead of a yellow one, on a base that had expanded during World War II to claim rivers, creeks, swamps, and mile after mile of Atlantic oceanfront.

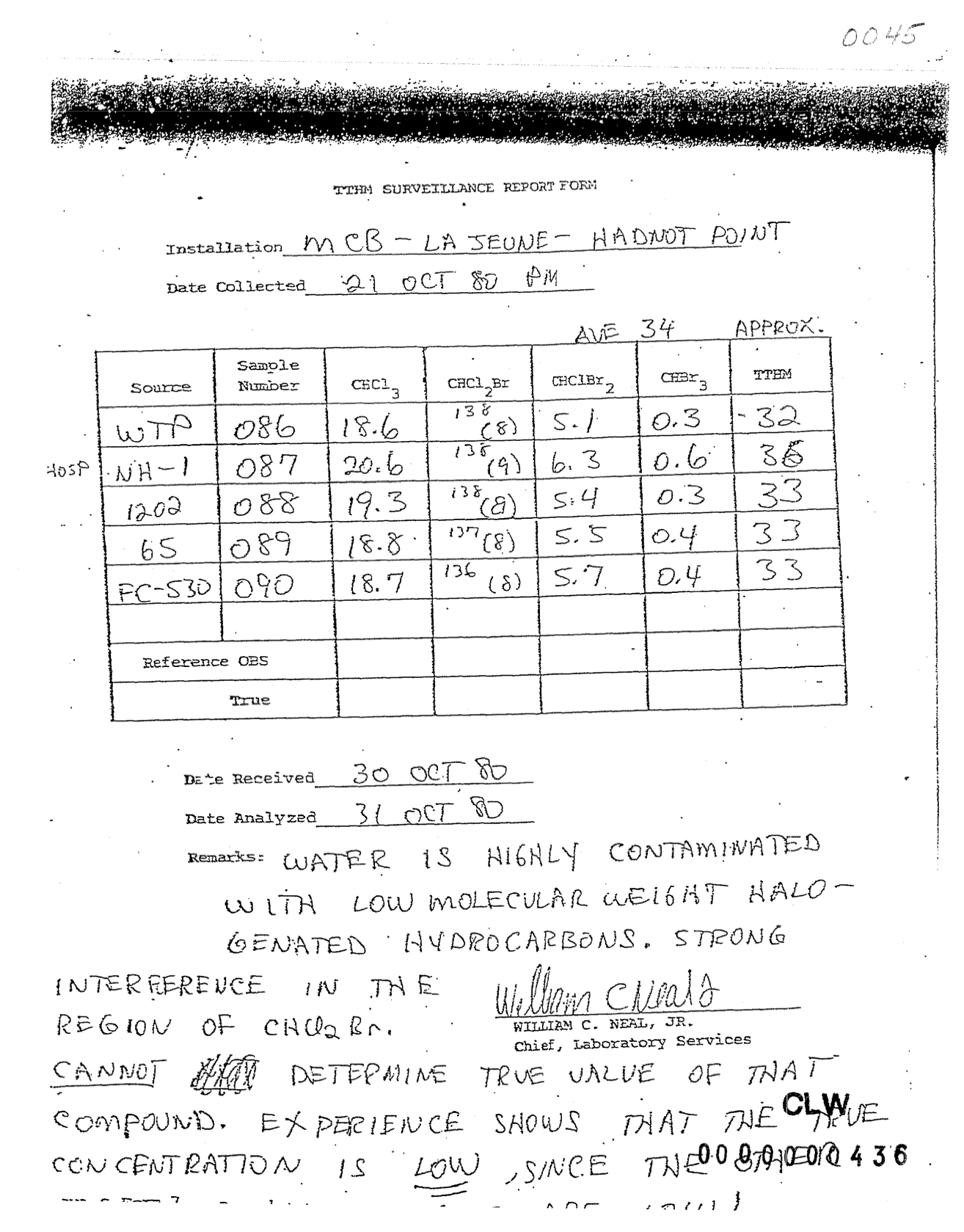

Early in the unfolding tragedy, the Army sent a note to Marine leadership about water-testing results. It was sent the same month that my mother wrote on the back of my fifth-grade photo: October, 1980. Army Laboratory Service Chief William Neal scrawled on the bottom of the lab results: “Water is highly contaminated with low molecular weight halogenated hydrocarbons.”

(Photo: Mike Partain)

It was an early warning about the drinking water on the base. But the Marines didn’t take any action that month or the next, and even after several warnings—including another handwritten note that exclaimed merely “Solvents!“—the Marine Corps waited five years to start shutting down contaminated wells. After that first memo, issued only days before the radioactive beagles were found, the poisoned drinking water kept flowing for several more years.

Camp Lejeune has been characterized as a candidate for the worst water contamination case in U.S. history—and I am one of up to a million people who were poisoned. The tragedy, though, is hardly all in the past.

According to the Project on Government Oversight (POGO), the military’s failures are continuing today; mistakes are being repeated at our bases overseas, and, in foreign cases, it took a whistleblower to prompt action on contaminated water. A 2013 investigative report produced by the Navy inspector general, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, reveals “shortfalls in the oversight and management of drinking water for Navy personnel stationed overseas—even in wealthy, developed countries.” The report concludes that “not a single Navy overseas drinking water system meets U.S. compliance standards” or the Navy’s own governing standards,” according to POGO.

How the Water Became Toxic

An important part of Marine culture is always being squared away—a code of personal cleanliness and etiquette that requires a pressed and starched uniform and a lot of shoe polishing. One of the dry cleaners that the Marines frequented to service their uniforms was ABC Cleaners, which operated out of a small, red- and white-painted building just across the highway from the base. Word traveled fast that they had the lowest prices, but the business produced more than money. Like any dry-cleaning outfit, it also produced tons of waste from the solvent used to clean the uniforms. According to a court deposition, ABC Cleaners used two to three 55-gallon drums of the solvent a month. That’s about three gallons of muck a day.

This dry-cleaning business is across the street from the entrance to my school. The owner used the toxic muck to fill potholes in his parking lot, and threw the rest into the drains.

In other areas on the base, waste was generated and discarded into empty lots, forests, roads, waterways, and makeshift dumps. That toxic waste was then taken by the Carolina rains and summer thunderstorms down toward sea level, into water wells, and into the barracks, houses, trailers, offices, and schools—and finally into the bodies of thousands of Marines and their families: into our cells, into our bones.

(Image: Alana Pipe)

In 2014, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), issued a position on the water at Camp Lejeune. The ATSDR found that “past exposures from the 1950s through February 1985 to trichloroethylene (TCE), tetrachloroethylene (PCE), vinyl chloride, and other contaminants in the drinking water at the Camp Lejeune likely increased the risk of cancers.”

In addition to those toxins, there was also benzene, a clear, colorless, and highly flammable chemical. When you put gas in your car, that smell you notice is benzene—an important petroleum byproduct that is also used in industrial solvents.

In the universe of environmental contamination, language can be complex, murky, and often confusing. When it comes to benzene, though, the language is like the chemical itself, perfectly clear: Benzene is a carcinogen. Benzene is a well-established cause of cancer in humans, and benzene causes acute myeloid leukemia.

The EPA has established a maximum contaminant level goal of zero parts per billion for benzene in public drinking water systems. In 1980, Naval Facilities Engineering Command testing showed that one of the wells at Camp Lejeune measured 380 parts per billion.

In 2010, the Associated Press found that a contractor “dramatically underreported” the level of benzene found in Lejeune’s tap water. Per the AP’s reporting, in 1992, when ATSDR visited Camp Lejeune to start its public health assessment, they found that a contractor had erroneously documented the 1984 level of benzene in one well was 38 parts per billion—when the actual measurement had been 380 parts per billion. The same contractor’s final report, issued in 1994, conveniently omitted the benzene altogether.

“The Marine Corps had been warned nearly a decade earlier about the dangerously high levels of benzene, which was traced to massive leaks from fuel tanks at the base on the North Carolina coast, according to recently disclosed studies,” the AP reported.

The chemical stew found at Lejeune is made of volatile organic compounds. They are able to vaporize, and, with ultimate stealth, to enter soil and air as gases, which then become your invisible companions. Finally, they come for the ones you love.

When the Water Becomes Vapor

A friend of mine describes the humid days in North Carolina as feeling like you are in a dog’s mouth. It can be brutal. Take a shower and walk outside and you need another shower. The only thing to do is drink lots of water and search for shade. Our school had an open plan, no enclosed hallways or air-conditioning, so on hot days teachers marched us to the old metal water fountains after recess. Then there were the “black flag days,” which meant that it was too hot for recess. In the cafeteria, we lined up for strange-tasting meat patties on plastic trays that were still warm and damp from the wash cycle. I can still smell all that dirty steam coming from the industrial dishwashers. We were breathing it, the toxic vapors, but the cafeteria ladies serving us were right there in a fog of it all day long, wearing hairnets and gloves out of what is, in retrospect, a heartbreaking concern for the students’ health and safety.

In homes across the country, vaporized poisons from underground can also be stealth killers. The dry-cleaning business down the road might be accidentally responsible for polluting the air in someone’s home. This is because of something called soil vapor intrusion, the process by which chemicals migrate from contaminated soil and groundwater into the air of indoor structures where it then sits, essentially trapped. The EPA issued its first guidance on vapor intrusion in 2002. In 2003, the George W. Bush administration ended that guidance. President Barack Obama then made it a priority—and the EPA released its final Vapor Intrusion Technical Guide in 2015.

Mike Magner, author of A Trust Betrayed, says that he thinks vapor intrusion is “the next big firestorm for the Pentagon, not just at Camp Lejeune but at military bases and former bases around the country.”

“There is plenty of evidence that the air is or has been toxic inside some of Lejeune’s buildings—there are test results being covered up but that will eventually come out—and there is a good possibility that either legislation or litigation will force the government to address this problem,” Magner says. “If the Marines are worried about their liabilities for the water contamination at Camp Lejeune, they ain’t seen nothin’ yet.”

Some years ago, I became a member of the Community Assistance Panel, a group mandated by congress to represent the Lejeune community working with the scientists at the CDC and with bureaucrats at the Veterans Administration. Through this work, I’ve learned more about the military’s cover-up of the water contamination, and how the culture that says “Stay Marine” also ensures that some problems remain entombed in secrecy.

The Community Assistance Panel has obtained more than 22,000 documents from an in-progress vapor intrusion study on the buildings at Camp Lejeune up to the present time. The study documents a clear and ongoing risk of exposure, as the groundwater plumes and utility lines—the pathways of exposure—are still located under the buildings.

This summer, a report to the CDC said that a recent test, at a building used as a barracks, had revealed the “highest recorded on-base indoor air TCE [trichloroethylene] detection due to vapor intrusion” since the EPA issued its guidance. This measurement exceeds both state and federal screening levels, which can cause health problems for those exposed, especially women who are in the first trimester of pregnancy. Which brings me back to my mother.

The Damage Is Done

My mother grew up poor on a farm, traumatized (she said) from having to break chicken’s necks, and dropped out of high school mid-way through. But Mary Freshwater knew her powers, and they were a force when she conjured them.

In 2007, the National Academy of Sciences convened a panel to talk about the water at Lejeune. It took place at the Jacksonville USO, the oldest USO building in the country, which sits on banks of New River under old Carolina shade trees. My mother was sitting in the audience while experts went on about statistics until it was time to hear from the people affected by the poisoned water at Camp Lejeune. Mom was there to tell them about Rusty and Charlie, the two babies she’d lost: one born with an open spine, the other with no cranium. Behind my mom, the Marines and family members were there to listen and tell their own stories.

(Photo: Lori Lou Freshwater)

Wearing a light pink turtleneck, her hair an uncharacteristic mess, she stepped up to the microphone and placed a small cardboard box on the podium in front of her. In black marker in small letters on the top of the box was the word Baby. This was all my mom had left of Rusty, my brother who had lived a month and died on New Year’s Eve in 1978.

As she spoke, she opened the baby box and unpacked it, eventually holding up a dingy bottle with the nipple still on it and liquid still inside, and a blue onesie, with a yellow stain which she would explain was her son’s vomit that she had not been able to wash.

“We are not numbers in a study. We are human beings that have had great tragedies,” she said.

After my mom died, this same baby box was one of the things I knew I had to find and keep. She had it with her all the time, even as we moved all over the place. It was my family history, but it was also now something public—a part of the country’s history too.

My mom’s leukemia, and her unwillingness to give up the fight, made her extended illness one of terrible suffering. After her death, my mother’s much younger husband fell apart and fell into the bottle again. One night I got a call saying that he hadn’t paid the rent and that the landlady was putting all my mom’s stuff in the old barn out back. Some cousins had already shown up and taken things. I was living in Rhode Island and had to drive down to rural North Carolina overnight. By the time I could get there the place was a mess.

After a few minutes of walking around the house, I was able to find the baby box.

It was sitting with junk, looking like the next candidate for the trash. I went into the kitchen to get some water; it was hot already and I was thirsty. On the counter there was another box, and this one stood out because it was new and had no name.

I opened it. Inside was a clear bag of ash and small fragments of bone. It was what was left of my mama. It was the first time I had seen someone’s ashes like that. It was not what I expected, not elegant ash like the kind the Kennedys would puff into the air from their boat and watch settle into the sea. Instead, it was undeniably the remnants of a human being, heavy with bits of stubborn bone.

I went and got my little brother’s box and sat it on the counter too. Right next to her.

And then, after packing up as much as I could, I took them both home.

The New River is not one of the most beautiful rivers. The banks are scrappy, with wild bushes crouched and waiting to sting your legs. It starts and finishes in Onslow County. It is our river, and it seems to say it is majestic until it makes believers out of us all. Sometimes it looks like the banks are falling into the water, like a claw came along and took root and dirt, rot and leaves. This kind of thing can look spooky. Maybe because we want to wonder, but never actually know, what is buried. We don’t want a storm to come along and dig up the things that have been covered, forgotten.