(Photo: Rebecca Kiger)

Jim Probst’s house and adjacent furniture shop are in Hamlin, a town in Lincoln County, West Virginia. Hamlin is populated mostly by trees clustered along soft, low-lying hills. The main road at some point tapers into two narrow strips of gravel, arced by the high boughs of trees. (When giving me directions to his house, Probst cautions, “You will think you have come to the ends of the Earth.”) When I first arrive at his place, Probst is waiting for me outside, wearing bronze-rimmed glasses, jeans, and a loose-shirt with a pen clipped to the pocket—a permanent fixture, along with a notebook to jot down any stray thoughts.

Probst seems to operate with two expressions: a wry scowl or a wide-mouthed smile. When discussing climate change, you can expect either one to surface on his face. As we sit on his front porch and talk about the seemingly impossible challenge that lies ahead—one not just of climate change mitigation, but also economic turbulence—he peers ruefully into the clear Appalachian sky.

“I’m 66 years old,” he tells me. “I’ve lived my whole life off the benefit of fossil fuels, and then leaving behind this world that’s going to hell.” Two of his grandchildren, Elliot and Eva, play on the front yard. Probst turns his gaze in their direction, his voice continuing: “The thought of my grandkids at some point saying: ‘My grandparents knew about this. What were they doing? Did they just ignore it?'”

For the past five years, Probst has dedicated himself to building a climate movement focused on transitioning West Virginia away from its fossil fuel-centered economy. It’s a quixotic goal (and, in a nod to Miguel de Cervantes’ iconic dreamer, Probst describes himself as a “tilting at windmills kind of guy”) given that the Mountain State is the largest producer of coal east of the Mississippi. Probst cringes when he hears people go on about how, as the coal industry shutters, people will need to uproot and move to Cleveland. “That’s the opposite of a just transition,” he tells me, referencing the concept, popular in climate circles, of a concurrent shift in energy resources and employment opportunities. It is, essentially, the idea that those very people who mine our coal and drill our wells, and the communities they live in, don’t get left behind. It is Probst’s hope that, with enough people and organization, a just transition from coal to clean energy will be possible.

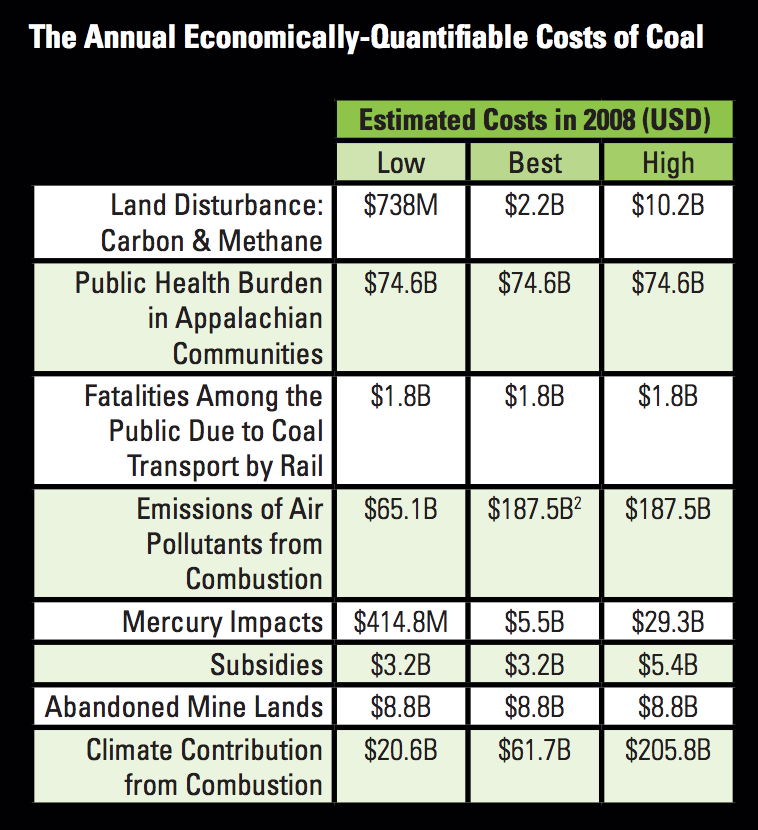

West Virginia has long been plumbed for its resources—first timber, then coal, gas, oil. People often claim that coal is the cheapest source of energy, but that estimate doesn’t incorporate its total cost, namely the toll it takes on the land, water, and miners’ health. To that end, a study from the Harvard University Center for Health and Global Environment estimated $345 billion in “external costs” for coal, a figure that factors in pollution and communities’ health.

It’s this accounting for the community, Probst claims, that’s so often lacking in climate activism. “A just transition means putting the needs of the workers, families, and communities that will be most affected by the transition to renewables first, over shareholders dividends and company bottom line,” Probst says. From a strategic standpoint, this makes sense: Show the people that you care and suddenly your cause becomes much more palatable.

A furniture maker for most of his life, Probst’s interest in climate work waned and waxed for some time, but then solidified when he became a grandfather in 2011. It was then that he began thinking more critically about the future of his grandson, Elliot. Probst attended an introductory session with the Citizens’ Climate Lobby, a grassroots non-profit, created in 2007, that trains people to become citizen lobbyists, helping them forge relationships with both congressional representatives and newspapers’ editorial page editors. It’s a pragmatic organization, and one that’s had some promising results: The group held 1,669 meetings with members of Congress in 2017; in 2010, the earliest year for which data is available, it held 106 such meetings.

Not long after Probst attended the intro session in late 2013, Elli Sparks, the field development director for Citizens’ Climate Lobby, dialed up the furniture maker. Sparks had a simple question—a persuasion, really: Why not act as a coordinator and make your own series of chapters in West Virginia? Probst recalls talking to his wife, Glenda, after the call. Her response, in Probst’s own words: “Well I guess somebody has got to do it.” That was all it took. He’s has since been devoting his time to creating chapters—five in all—throughout the state.

Probst leads me into his furniture shop. This is where he still spends most of his mornings even though he is retired (it’s apparently a word he uses more in theory than practice). The interior of the shop feels like it belongs to an industrial artist: everything in its proper place, no signs of sawdust or stray materials, aside from a sign that reads “Probst Furniture Makers” propped up on a wood stove. Probst built the shop himself using ash trees from his property. Today Probst is in high spirits: He’s just gone to the barber for what he refers to as his “go-to-Congress haircut.”

Probst and his cohorts will be traveling to Washington, D.C., the next day to lobby and on behalf of the Citizens’ Climate Lobby. By now, Probst is an old hat at this. “I’ve had a coat and tie on more times in the last five years than I have in the last 66 years of my life,” he jokes. He estimates that he has had a total of 60 meetings in congressional offices, including face-to-face meetings with both of West Virginia’s senators, Shelley Moore Capito and Joe Manchin, and his congressman, Evan Jenkins.

Just a day prior to my arrival, Probst finally wrote down his lobbying strategy for the trip: He intends to push for the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, a federal fund established in 1969 to support coal miners with black lung and their families in cases where their employer has gone bankrupt. Currently, one in five miners who have been working for over 25 years have black lung, a debilitating, painful, and yet preventable disease.

A recent NPR investigation found a spike in cases of advanced black lung disease—more recorded instances than ever before. Despite the dire need, the fund is set to be slashed by 55 percent, according to a recent report from the Government Accountability Office. Probst sees this fund as a safe starting point for a conversation that will allow him to build up to harder demands. “So once again we can talk economic development and then, you know, we could also talk about how this helps with the transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy, which will then lead to climate change,” Probst says.

(Photo: Rebecca Kiger)

He will also be lobbying for the Revitalizing the Economy of Coal Communities by Leveraging Local Activities and Investing More Act (better known as the RECLAIM Act), proposed legislation that would redistribute money into economic revitalization projects in abandoned coal fields, which present a huge public-health liability. If passed, the RECLAIM Act would invest 200 million over five years in West Virginia and, in turn, create jobs in reclamation work—the kind of jobs that many people are already skilled for in West Virginia. While all the funds from RECLAIM would go toward reclamation projects, they would also be tied to long-term economic development projects. What’s more, Probst believes the RECLAIM Act and the Black Lung Trust Fund could together satisfy wonky and byzantine congressional spending rules: The increased revenue in the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund could act as a federal offset necessary to accelerate the disbursement of existing funds under the RECLAIM Act.

The goal for the RECLAIM Act is that it would not be just a temporary fix, but would ensure long-term planning around future work opportunities in a given area—an objective that Probst sees as necessary before a transition to clean energy can be achieved.

The issue of a transition lies not just in fossil-fuel dependency, but also poverty, which has a firm grip over Probst’s own Lincoln County, which is 24.2 percent below the poverty line, according to the United States Census Bureau. (Probst estimates that he sold 80 percent of his furniture to out-of-state buyers.) Still, Lincoln fares better than others—for example, McDowell County, where 36.3 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. (According to an article in the Guardian, McDowell County has a population of 18,000, compared to 100,000 in 1950, when the area was a major coal producer.)

Necessity, they say, is the mother of invention, and Probst’s career as a furniture maker is no exception to that proverb. In the 1970s, he and Glenda had just moved into a small, frameless house, entirely supported by its sideboards, with no running water or electricity. (That house sits about three-quarters of a mile from his current one.) They needed furniture, so he built a set of rickety bookshelves. They weren’t exactly artisan-quality; they could barely stand up straight.

But he kept building furniture. Eventually his pieces became both more functional and more artistic, drawing on the clean-lined elegance of Shaker and missionary furniture. His latest pieces, organically shaped pieces of walnut wood balancing on a more narrow base, are meant to resemble ice calving, the process where sheets of ice break off from the glacier. Ice calving contributes to overall sea level rise, which has, in turn, heightened the intensity of flooding in West Virginia in recent years.

A rivulet of amber-colored hand-blown glass runs through the walnut wood, meant to signal this harsh divide of ice from glacier—a moment that Probst fears, and a moment that motivates him to keep working.

A just transition for West Virginia is not just about the economy, but is also cultural. Probst is influenced by the work of Nick Mullins, a writer and lecturer on justice issues in Appalachia. Mullins, a former coal miner, talks frequently about the ways the environmental movement has stereotyped and failed to listen to Appalachians, causing them to feel unrepresented in the movement. Environmentalists often fail to account for the fact that many coal miners don’t want to be coal miners, but, like Mullins, fell into it out of necessity. “Coal miners are not anti-environment; if anything they are anti-environmentalists,” he tells me.

But a just transition is not a concept that’s explicitly built into the larger Citizens’ Climate Lobby agenda, which focuses on pushing for a federal carbon fee. By placing a fee of $15 per metric ton of C02 equivalent emissions imposed at its point of sale, they hope to account for the overlooked health and environmental toll of carbon. This fee would be collected by the Department of the Treasury and returned to affected households every month as a dividend. If passed, in 20 years, a carbon fee and dividends is projected to reduce carbon emissions by 50 percent below 1990 levels and avoid 230,000 premature deaths.

But a carbon fee would also be a tough sell in a place like West Virginia, where it would quickly hasten the decline of coal, the most carbon-intensive fuel. The national leadership of the Citizens’ Climate Lobby recognizes this; they’ve given Probst their blessings in shifting the goals of his group, to be more aligned with West Virginia’s needs in preparing for this future. “Being totally transparent, I don’t know where their work is going to lead and it might not end up with those folks getting on board with carbon fee and dividends, and that’s ultimately OK,” says Daniel Richter, the vice president of government affairs of the Citizens’ Climate Lobby. “I think they’re starting from the right place—they’re starting with a place that’s important to them, to the community.”

(Photo: Rebecca Kiger)

Another approach, adopted by climate justice groups like the New York Renews coalition, is for frontline communities (i.e. those more affected by climate change) to receive a higher percentage of the dividends, and for the allocation some of the funds toward investment in green infrastructure and jobs in those areas. New York Renews’ philosophy is predicated on the idea that, from the onset, bolstering disadvantaged communities should be emphasized. That’s in contrast to the national agenda of the Citizens’ Climate Lobby, which makes the case that a scheme wherein the money collected from the fee is distributed evenly—known as a revenue-neutral approach—has the best chance of passing in Congress.

It’s a narrow but important policy question: How and when do we account for those who will be most affected by the transition to clean energy? For Probst, the answer became clear early on. “Just going into West Virginia congressional office and asking for a fee on carbon emissions,” he says, “they just smile at us and say: ‘That’s nice. We don’t want to do that.'” Probst realized he would need to shift his strategy to better address the communities who would be most affected by this policy before anything else.

A few days after our meeting at his home, Probst and a handful of his team sit in the ornate Omni Shoreham Hotel in D.C. They’re here for the Citizens’ Climate Lobby Conference, where members from all 50 states meet to discuss lobbying strategy. As a state coordinator, Probst is expected to deliver a few quick remarks and a progress update. Most of these speeches center, not surprisingly, on carbon fees and dividends and membership growth.

But Probst has a different address in mind. Holding a heavily underlined GAO report on black lung, Probst warns everyone that he’s “about to go off the rails.” He continues:

Black lung is a debilitating, painful, fatal disease. There is a fund that’s known as the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund and coal companies pay a per ton excise tax on it. It is currently running at a one billion plus deficit on a yearly basis. You and I make up that difference. But the fund is intended to assist miners who have been afflicted with black lung disease with their treatment, helps to support their families and their widows.

Probst goes on to talk about how extending the Black Lung Disability Trust could be paired with additional long-term economic revitalization efforts through the RECLAIM Act, and urges everyone to pick up a flyer to bring to their lobbying meetings. He concludes his decidedly non-environmental speech, delivered to environmentalists: “This is a national disgrace, to allow an industry’s workforce … to be sacrificed to a disease and not have the industry that is employing these people have to take care of their workforce.”

Probst apologizes once more to the hushed audience for throwing them for a loop. His soliloquy is met with a resounding applause.

A few days later, when Probst is back in Hamlin, he muses on the conference. “I’m pretty tickled by the fact that we had members from five different groups in West Virginia and all three congressional districts [represented] in D.C.,” he says. “That’s progress and I’m proud of it.”