By November of 2018, Natalee Fisher was well into her transition. For nearly a year, she had seen a therapist and begun hormone treatments. Her business partner and employees were used to her appearance in heels, painted nails, and blonde hair at StickyLife, their small decal and sticker business in Raleigh, North Carolina. To all who knew her, she was a 39-year-old woman.

Then November 6th, Election Day, arrived.

Fisher panicked. She wanted to vote, but worried about the reaction from neighbors and poll workers when she showed up as a woman while her driver’s license read “Nathaniel.” Usually, in states with more lenient voter ID laws, like North Carolina at the time, poll workers would primarily verify that the address listed on the ID matched the ID listed on the voter roll, and not necessarily scope for corresponding gender. But as a trans woman, Natalee’s fears abounded about the complications that could arise given that her ID’s listed gender was different from her gender presentation.

Changing the gender on her driver’s license was out of the question: At the time, in North Carolina, it required proof of sex reassignment surgery, documentation of these procedures by a doctor, a change of listed gender with the Social Security Administration, and more. The process was both expensive and invasive.

She wondered if going to the polls as the woman she is would create a scene. Would she be escorted out? Could her right to vote even be in jeopardy?

Fisher eventually came to a solution that saddened her and betrayed her true identity: She went to the polling place dressed as a man.

In the polling center, in men’s clothes, Fisher returned to a more complicated phase of her life, a time when she hid her true self even from the wife she deeply loved. “I stood there in that voter line wearing clear glossed fake nails, girls’ socks that weren’t visible, and panties just to feel comfortable in my own skin,” Fisher recalls. It was a stark reminder that, as a transgender woman, neither her place in society nor her constitutional rights seemed guaranteed in an America where various state governments are enacting discriminatory policies to keep minority groups from the polls.

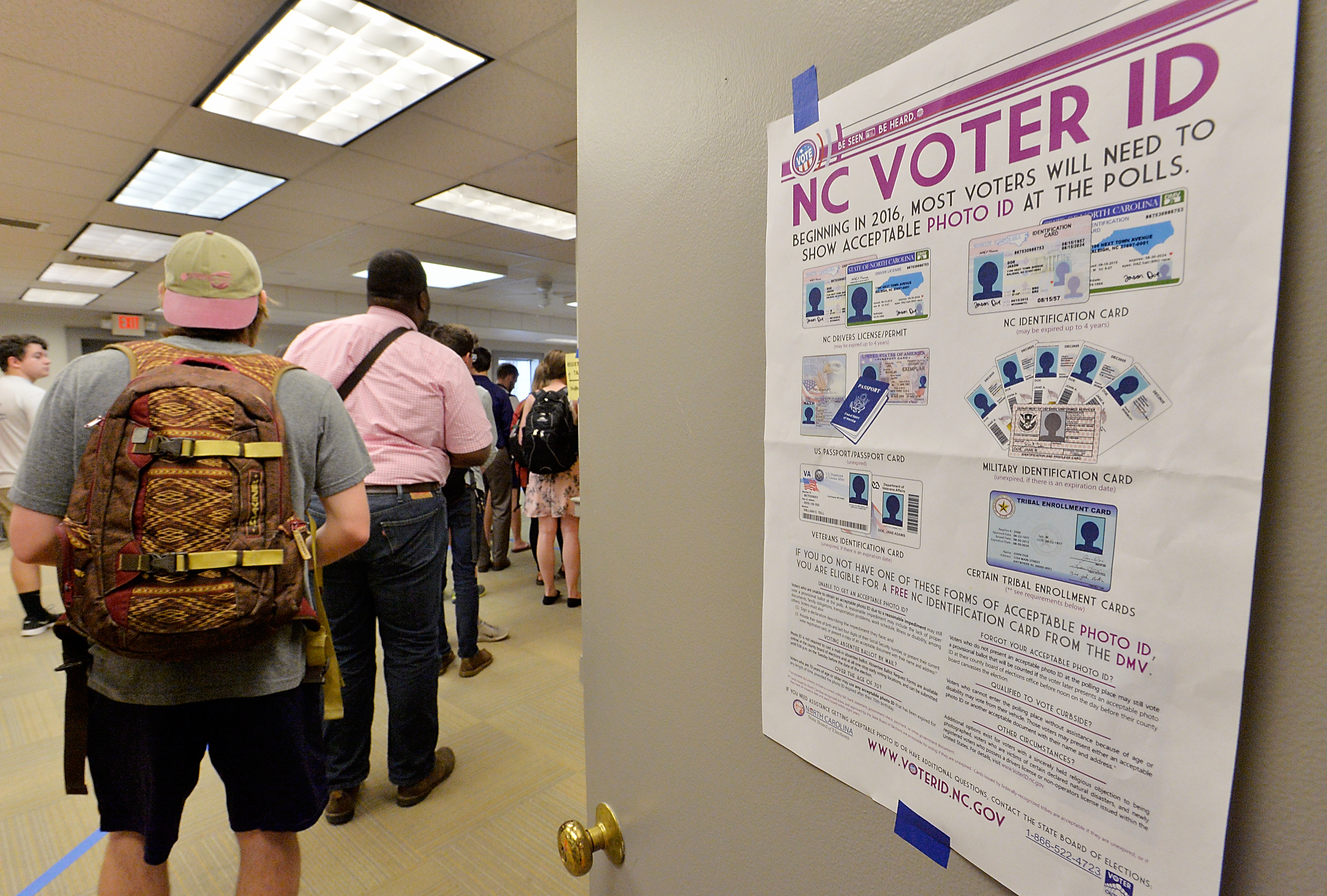

During the 2018 mid-term elections, voters in 17 states had to show state-issued photo ID to vote. Seven of those 17 states are strict in their enforcement: If a voter does not have the right photo ID, they can only vote provisionally and are required to follow up after Election Day. North Carolina wasn’t included in that list in 2018, but on its ballot was a measure to make the state’s voter ID laws some of the harshest in the country despite all the studies that show that such laws disproportionately impact black and Latino voters.

For years, North Carolina did not require a photo ID to vote, despite numerous attempts to gerrymander and implement voter ID laws. But on November 6th, 2018, 55 percent of North Carolinians approved a constitutional amendment that goes in effect in 2020 and requires some of the nation’s strictest voter ID laws. Solidified into law by an overriding of Governor Roy Cooper’s veto 72–40, the amendment requires North Carolinians to show photo identification before casting ballots at the polls.

Largely overlooked in the public debate and court hearings on Voter ID laws is their effect on another demographic: the transgender community. North Carolina’s new laws could put barriers in the path of trans people trying to vote. The Williams Institute at the University of California–Los Angeles School of Law estimated in 2018 that strict voter ID laws in eight states stood to disenfranchise upwards of 78,000 transgender people that year. With North Carolina becoming yet the newest state to enact equally strict voter ID laws, the number could have become much larger for 2020 without the quiet and intentional activism of a small group of transgender people and allies.

As the state made ID laws stricter, the North Carolina trans community, motivated in part by fear of what was coming, worked to ameliorate the process for changing genders on drivers’ licenses. Since January, the North Carolina Department of Motor Vehicles has significantly eased the process and allows anyone to change their sex on their driver’s license; the change still requires endorsement, but that can come from a variety of officials, including case workers, social workers, physicians, physician’s assistants, psychiatrists, psychologists, licensed therapists, or counselors.

North Carolina’s bathroom bill (the Public Facilities Privacy & Security Act) galvanized many Americans on behalf of the trans community in North Carolina, but the challenges the community faced went far deeper than the one bill alone. The general population interacts easily with bureaucracies, but for trans people, dealing with an outdated listed gender was a herculean task. Simple events and interactions with state agencies, like those at a polling center, induced fear and terror. In the case of Natalee, outdated ID’s made casting a ballot a dangerous affair. In other notable cases in the state, it cost invitations to high-profile events, and made daily life fraught. As Ames Simmons, a trans man and Director of Transgender Policy at Equality North Carolina, says, with a misgendered ID “you can instantly become subject to a different form of violence: administrative violence.”

As a child, Elaine Martin, first realized that she was female around age six. She recalls, “My first experience was trying to wear a silk lampshade.” At age 11, she was looking through her parents’ collection of old LOOK magazine articles. A picture of Christine Jorgensen, who had sex reassignment surgery not long after serving as a drafted enlistee for the United States Army during World War II, graced a spread of the 1952 issue of the magazine. Martin, “just mooned over it. … I just remember thinking this can happen, you know? … I remember going to sleep and hoping that an angel would come in the window and I could somehow wake up transformed.”

Years later, in 2009, Martin was invited to a briefing on LGBT issues at the White House. A leading trans rights activist, Martin chaired the board of Equality North Carolina. She knew White House visits required background checks, and it occurred to her she hadn’t changed her social security records yet. “When I go, I’m going to be Elaine Martin and I’m going to look like I’m Elaine Martin,” she recalls thinking, “but my Social Security card hasn’t changed yet, and I don’t want to get caught in one of those gender incongruent situations.”

Martin declined the invitation, but decided, “if you’re going to be an activist and you’re going to be out there, and I was very out at that point,” that she needed her documentation in order and to change the process. “We’ve got to fix that somehow—you just got to fix it,” she recalls thinking.

(Photo: Sara D. Davis/Getty Images)

Only a year later, she found even checking into a hotel for a Human Rights Campaign banquet would prove difficult. As she puts it, “The whole hotel was full of queer people and when I tried to check in, they wouldn’t let me because my driver’s license didn’t match [the name of] my [hotel] registration.” Another time, she tried to replace her lost room key in an Atlanta hotel. “They wouldn’t believe that I was the person on the room reservation because my appearance was Elaine Martin and I had to prove I was me and I had no idea how I could prove it was me.”

Martin eventually acquired an ID that identified her as a woman. When Martin changed her gender marker in 2010, the North Carolina DMV guidelines were vague. The guidance was a single clause: “If a customer desires to change gender code on driver’s license or ID card, a court order or physician’s statement verifying procedure must be presented.” This allowed DMV clerks to determine if the applicant’s appearance was, as Simmons puts it, “trans or transitioned enough.” For some trans people, this meant answering intrusive questions in public DMV offices about their genital make up, procedures undergone, and treatment received.

In 2011 when Bev Perdue, a Democrat, was governor of North Carolina, Martin and her team created a gender designation form that would allow trans people to select the gender that most reflected who they were without having to undergo surgery or without need for a physician to confirm treatment or surgeries. But within 24 hours, the under-the-radar plan tanked when an attorney in the Republican attorney general’s office deemed that they would not approve this administrative change—arguing that it needed to be legislated.

By 2017, under Republican Governor Pat McCrory, North Carolina’s administrative guidelines for getting a gender marker changed became more stringent. The physician’s statement had to “indicate that surgery, not merely ‘treatment,’ was completed.”

But once Democratic governor Roy Cooper was elected in 2017 with Democratic Attorney General Josh Stein, Martin and Simmons reignited the fight. This time, they won, changing the DMV guidance to allow trans people a faster, easier, less-intrusive way to change their gender to reflect who they actually are.

For Kaye Vassey, an accomplished animator, getting invited to a speak at a conference in Canada was exciting, but her attendance would require an updated passport, and that inspired fear. She recalls wondering: “Would my current passport that lists me as a male get me into a trouble? Would they accept me as who I am or would they be confused?”

Vassey, now 41, needed a passport that reflected who she is. She was already down the path of changing her name, a standard process that is no different for trans people than for anyone else. Surprisingly, she found the passport process quick and easy: In June of 2010, the Department of State changed its policy from requiring proof of specific medical treatment to a simpler form from a physician confirming clinical treatment of some kind. As she says, “there’s an easy, fill-in-the-blank form” available online. She sent the form to her medical provider and therapist and a short time later she received her passport. With the help of a trans attorney, updating her social security card also went smoothly. But the ease of the process would end when it was time to change her driver’s license.

Under the 2017 DMV regulations in North Carolina, surgeries and treatments had to be documented. A DMV clerk, called an “examiner,” had primary responsibility to determine whether the documents matched the person under review. As recommended by her lawyer, Vassey was professionally dressed when she went to the DMV. She chose the Carborro, North Carolina, location, which had a reputation for being very liberal, a safe haven that borders multiple college towns.

(Photo: Sara D. Davis/Getty Images )

Vassey went to the clerk with her binder full of documents collected and organized by her lawyer. She remembers how comfortable she was made to feel as the DMV clerk told her “Oh my sister is transgender, and it was just so awesome!” Vassey handed the clerk her paperwork. But as the clerk read the physician’s statement, she said, “I don’t think this is going to work because it has to demonstrate irreversible physical change.” Essentially, the wording of the physician’s statement didn’t make Kaye “trans enough,” in the clerk’s eyes.

The clerk’s supervisor supported the clerk. And despite her pleas, Vassey couldn’t get the gender marker change. Every time she showed her ID with the changed name and changed picture, but with the “male” designation, she essentially outed herself to everyone viewing the license.

“It is so messed up that the Social Security Administration says ‘female’, the IRS says ‘female,’ and the State Department [through the passport] says that I’m female and has given me an ID that says I’m female. And yet this state and its driver’s license still says ‘M’ because they just want to make it hard,” Vassey recalls thinking at the time.

This March, less than a month after reassignment surgery, Vassey heard about the DMV guideline changes allowing her to designate who she is. In a 10-minute visit to the DMV, she had the female designation on her license.

Around the country, there are transgender people suffering similar indignities.

The 2011 National Transgender Discrimination Survey found that only 33 percent of transgender people have “surgically transitioned,” which remains a barrier to change IDs in 10 states. Despite the relaxed DMV requirements, only 10 percent of trans North Carolinians have “all of their IDs reflecting the name and gender they preferred.” The costs associated with the transition of those documents serves as a hindrance: The unemployment rate among trans North Carolinians is nearly four times the national unemployment, and nearly 30 percent of trans people in the state are living in poverty.

“Many obstacles get in the way of modernizing gender change policies in other states, from bureaucratic agency barriers to a lack of understanding of transgender issues,” says Arli Christian, state policy director for the National Center for Transgender Equality.

There’s considerable inconsistency among the states regarding documentation for transgender people.

In states like Oregon and Maryland, trans people make their own decisions as to who they are and what their gender is: No medical or social services provider needs to certify anyone’s gender or sexual identity. If Vassey lived in Minnesota, where gender-neutral options are provided and no medical provider attestation is required, she wouldn’t have tussled with DMV officials about having the requisite information to change her gender marker. If Martin’s driver’s license was from Oregon, where the same rules as Minnesota exist, she wouldn’t have had disparate gender identity claims between how she presented and her driver’s license. And if Fisher had lived in Maryland, where the same rules as Oregon and Minnesota are observed, she wouldn’t have felt the need to dress as Nathaniel to avoid being outed during a routine casting of a ballot.

But in nine states, the process of changing IDs remains structurally difficult. In Alabama, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, proof of surgery, court order, and/or amended birth certificate are required to change the listed gender on a state ID.

When Simmons, then living in Atlanta, tried changing his listed gender on a driver license, Georgia required reassignment surgery and a notarized, certified letter from the surgeon who performed it. While Simmons’ top surgery was deemed sufficient for a gender change, the whole process of getting surgery, a letter from the doctor, and notarization was costly—altogether nearly $20,000, mostly in cash. He had the time and opportunity, as a salaried worker with a supportive boss, to change his gender marker—a luxury many trans people don’t have. If Ames had his way, we would “move away from letting these gatekeepers, whether they’re medical or legal, create these artificial barriers about who gets to be trans or trans enough.”

That’s what the DMV changes in North Carolina have allowed, in part. Brimming with pride, Fisher now brandishes her new ID. “Natalee Fisher” it reads, in bold, typeface capital letters with the capital letter “F” after the word “Sex” in the bottom, center-left, just adjacent to her smiling face. She never had to have surgery, and never wrangled angrily with a DMV clerk. Fisher, like every American, just wants assurances she can continue to vote without the approval of a gatekeeper to her identity.