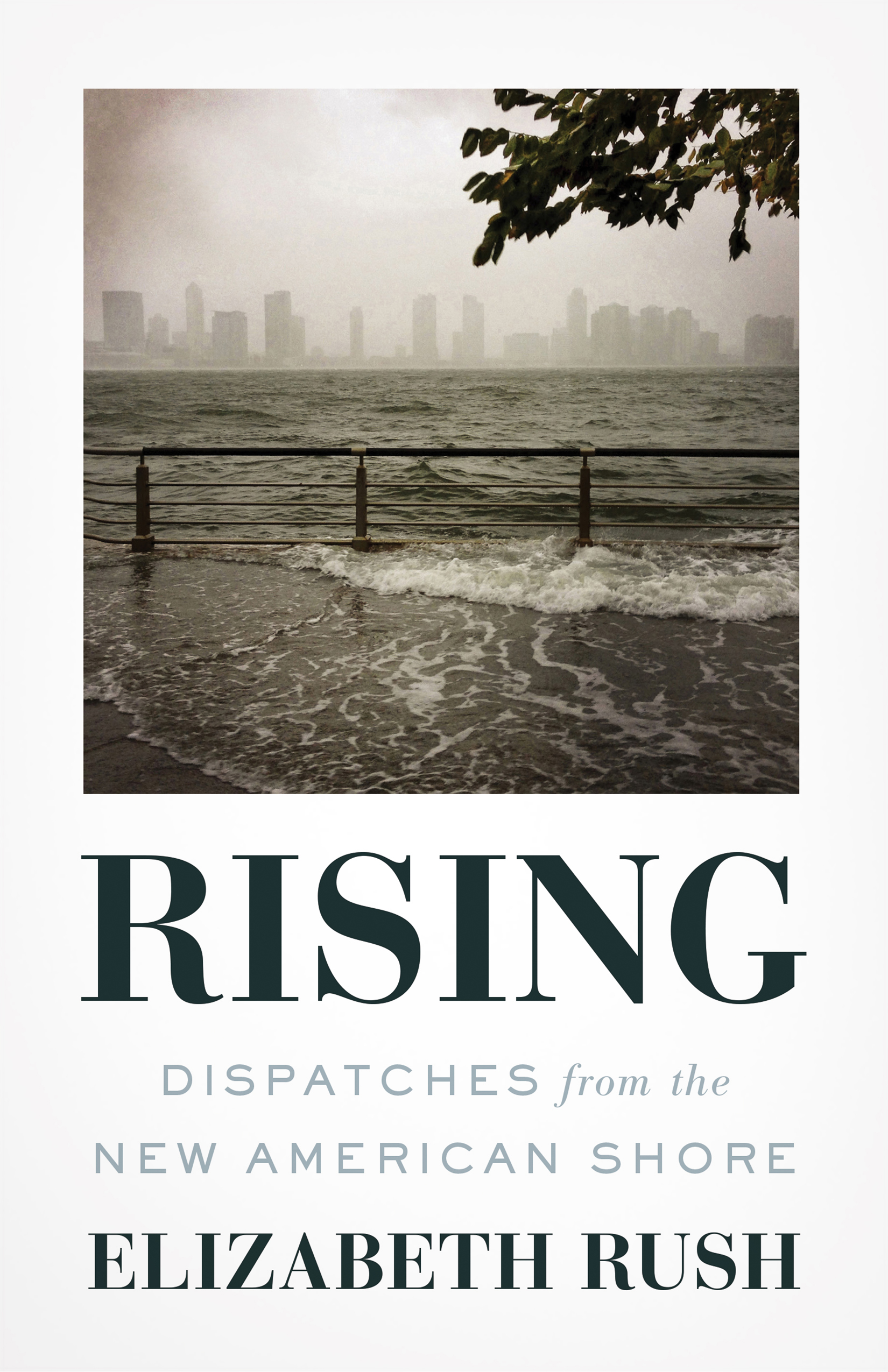

(Photo: Suzanne Lettieri and Michael Jefferson)

Excerpted From Rising: Dispatches From the New American Shore.

In 1890, just over 6,000 people lived in the damp lowlands of south Florida. Since then, the wetlands that covered half the state have been largely drained, strip malls have replaced Seminole camps, and the population has increased a thousandfold. Over roughly the same amount of time, the number of black college degree holders in the United States also increased a thousandfold, as did the speed at which we fly, the combined carbon emissions of the Middle East, and the entire population of Thailand.

About 60 of the region’s more than six million residents have gathered in the Cox Science Building at the University of Miami on a sunny Saturday morning in 2016 to hear Harold Wanless, or Hal, chair of the geology department, speak about sea level rise. “Only 7 percent of the heat being trapped by greenhouse gases is stored in the atmosphere,” Hal begins. “Do you know where the other 93 percent lives?”

A teenager, wrists lined in aquamarine beaded bracelets, rubs sleep from her eyes. Returns her head to its resting position in her palm. The man seated behind me roots around in his briefcase for a breakfast bar. No one raises a hand.

“In the ocean,” Hal continues. “That heat is expanding the ocean, which is contributing to sea level rise, and it is also, more importantly, creating the setting for something we really don’t want to have happen: rapid melt of ice.”

A woman wearing a sequined teal top opens her Five Star notebook and starts writing things down. The guy behind her shovels spoonfuls of passion fruit-flavored Chobani yogurt into his tiny mouth. Hal’s three sons are perched in the next row back. One has a ponytail, one is in a suit, and the third crosses and uncrosses his gray street sneakers. The one with the ponytail brought a water bottle; the other two sip Starbucks. And behind the rows and rows of sparsely occupied seats, at the very back of the amphitheater, an older woman with a gold brocade bear on her top paces back and forth.

A real estate developer interrupts Hal to ask, “Is someone recording this?”

“Yes.” The cameraman coughs. “Besides,” Hal adds, “I say the same damn thing at least five times a week.” Hal, who is in his early 70s and has been studying sea level rise for over 40 years, pulls at his Burt Reynolds mustache, re-adjusts his taupe corduroy suit, and continues. On the screen above his head, clips from a documentary on climate change show glacial tongues of ice the size of Manhattan tumbling into the sea. “The big story in Greenland and Antarctica is that the warming ocean is working its way in, deep under the ice sheets, causing the ice to collapse faster than anyone predicted, which in turn will cause sea levels to rise faster than anyone predicted.”

(Photo: Milkweed Editions)

According to Marco Rubio, the junior senator from Florida, rising sea levels are uncertain, their connection to human activity tenuous. And yet the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change expects roughly two feet of rise by century’s end. The United Nations predicts three feet. And the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates an upper limit of six and a half feet.

Take the six million people who live in south Florida today and divide them into two groups: those who live less than six and a half feet above the current high tide line, and everybody else. The numbers slice nearly evenly. Heads or tails: Call it in the air. If you live here, all you can do is hope that when you put down roots, your choice was somehow prophetic.

But Hal says it doesn’t matter whether you live six feet above sea level or 65, because he, like James Hansen, believes that all of these predictions are, to put it mildly, very, very low.

“The rate of sea level rise is currently doubling every seven years, and if it were to continue in this manner, Ponzi scheme-style, we would have 205 feet of sea level rise by 2095,” he says. “And while I don’t think we are going to get that much water by the end of the century, I do think we have to take seriously the possibility that we could have something like 15 feet by then.”

It’s a little after nine o’clock. Hal’s sons stop sipping their lattes and the oceanographic scientist behind me puts down his handful of M&M’s. If Hal Wanless is right, every single object I have seen over the past 72 hours—the periodic table of elements hanging above his left shoulder, the buffet currently loaded with refreshments, the smoothie stand at my seaside hotel, the beach umbrellas and oxygen bars, the Johnny Rockets and seashell shop, the lecture hall with its hundreds of mostly empty teal swivel chairs—will all be underwater in the not-so-distant future.

Dig into geologic history and you discover this: When sea levels have risen in the past, they have usually not done so gradually but rather in rapid surges, jumping as much as 50 feet over three centuries. Scientists call these events “meltwater pulses” because the near-biblical rise in the height of the ocean is directly correlated to the melting of ice and the process of deglaciation, the very events featured in the documentary footage Hal has got running on a screen above his head.

Hal shows us a clip of the largest glacial calving event ever recorded. It starts with a chunk of ice the size of Miami’s tallest building tumbling, head over tail, off the tip of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Then the Southeast Financial Center goes, displaying its cool blue underbelly. It is a coltish thing, smooth and oddly muscular. The ground between the two turns to arctic ice dust and the ocean roils up. Next, chunks of ice the size of the Marquis Residences crash away; then the Wells Fargo Center falls, and with it goes 900 Biscayne Bay. Suddenly everything between the Brickell neighborhood and Park West is gone.

The clip begins again and I watch in awe as a section of the Jakobshavn Glacier half the size of all Miami falls into the sea.

“Greenland is currently calving chunks of ice so massive they produce earthquakes up to six and seven on the Richter scale,” Hal says as the city of ice breaks apart. “There was not much noticeable ice melt before the ’90s. But now it accelerates every year, exceeding all predictions. It will likely cause a pulse of meltwater into the oceans.”

(Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

In medicine, a pulse is something regular—a predictable throb of blood through veins, produced by a beating heart. It is reliable and steady, so definite that the lack of a pulse is sometimes considered synonymous with death. A healthy adult will have a resting heart rate of 60 to 100 beats per minute, every day, until they don’t. But a meltwater pulse is the opposite. It is an anomaly. The exception to the 15,000-year rule.

From 1900 to 2000, the glacier on the screen retreated eight miles. From 2001 to 2010, it pulled back nine more; over a single decade, the Jakobshavn Glacier lost more ice than it had during the previous century. And then there is this film clip, recorded over 70 minutes, in which the glacier retreats a full mile across a calving face three miles wide. “This is why I believe we are witnessing the beginning of the largest meltwater pulse in modern human history,” Hal says.

As the ice sheets above Hal’s head fall away and the snacks on the buffet disappear, topography is transformed from a backwater physical science into the single most important factor determining the longevity of the Sunshine State. The man seated next to me leans over. “If what he says is even half true,” he whispers, “Florida is about to be wiped off the map.”

A few days later I spend the afternoon in Shorecrest, a neighborhood a couple of miles north of downtown. To get there I leave the beach behind and drive past Arky’s Live Bait & Tackle, Deal and Discounts II, Rafiul Food Store, Royal Budget Inn, Family Dollar, and Goodwill. As I continue north, the buildings all lose their mirrored glass and their extra floors, until most are single story and made from stucco.

It isn’t raining when I arrive in Shorecrest, and there isn’t a storm offshore; the day is as clear and as blue as the filigree on a porcelain plate. But the streets are still full of water. I watch as a woman wades ankle-deep across Tenth Avenue. She has gathered her long russet-colored skirt in her right hand, and in her left she holds a pair of Jesus sandals. When she reaches the bus stop, she sits and puts her shoes on. On the corner a man stands facing traffic, holding a sign that simply reads, “Please help FOOD.”

“We get flooded with just about every high tide,” the woman tells me, glancing in the direction of the panhandler and the approaching bus. “And if the moon is big it’s worse.”

All along the East Coast, from Portland, Maine, to Key West, “sunny-day flooding” is increasingly frequent. Many places in the Sunshine State are so low lying that high tide—when coupled with something as innocuous as a full moon—can cause the streets to brim with water. Sometimes the tide simply rises above the seawalls and starts to spill into the roadways; in other cases it enters the neighborhood through the storm-water infrastructure belowground. The very pipes designed to reduce flooding by ushering rain out instead give salt water a chance to work its way in. In Shorecrest, I spend a minute watching the bay burble up through the street grate and onto Northeast Little River Drive before whipping out my camera and snapping half a dozen photos. Just then a man walks up behind me, peers down, and says, “I’ve seen fish come swimming out.”

“No, you haven’t!”

“I have,” he says, pushing his sunglasses up. “I’ve been here 20 years. When I first moved we used to flood once a year, maybe twice. Now it’s constant.” His name is Robert Cisneros. He grew up in Cuba and moved to Florida in 1962, dropping the final o in Roberto. He thought the name change might help his fledgling boat repair company succeed.

I had heard about the flooding in Shorecrest from Nicole Hernandez Hammer, a sea level rise researcher turned advocacy coordinator for the Union of Concerned Scientists. The daughter of Cuban and Guatemalan immigrants, Nicole left academia for activism when she observed firsthand the disproportionate risk that climate change poses for the Latinx communities of south Florida. “We know that people of color are often the most vulnerable to climate change, and that these communities also tend to receive disproportionately low funding for adaptation, resiliency, and relocation,” she told me over the phone. “You’re staying out on the beach, right? Just drive up to Shorecrest. It will take you 20 minutes, and you’ll see what I mean.”

(Photo: Suzanne Lettieri and Michael Jefferson)

Robert points to his house and his yard, which are catty-corner from the drain we stand by, and says: “I used to have a nice garden here, and now you see how it is. The water comes in and sits. And everything dies because of the salt. It’s not rain that floods this place. It’s the ocean. I just bought some stones to put here to try to keep the water out. But other than that, what can I do?”

I ask if the city is helping the neighborhood come up with short-term solutions. Robert gets upset. “I think they need to raise the street. They need to install pumps. But those kinds of things only happen on the beach. They’re not giving any of us here any relief.”

Like Miami Beach, Shorecrest was built atop a former wetland. On the strip, where billions of dollars in real estate investment are at risk, the government is using a mix of property taxes and municipal bonds to invest in formal sea level rise adaptation. But in Shorecrest, Hialeah, and Sweetwater—low- to- middle-income neighborhoods where the majority of residents are people of color and municipal services have long been difficult to maintain, thanks to the discriminatory banking practice known as redlining and the resulting decline in property taxes—residents are expected to remove their shoes and wade through the water.

Robert shakes his head in disbelief. “I wanted to leave this house to my kids, but soon it’s going to be worthless,” he says. On his stoop sit two pairs of rubber boots, ready for the flood that is already here.

The following Friday, as I drive from my hotel back to the Cox Science Center, I think about what would happen if all the water stored in Antarctica’s and Greenland’s ice sheets were released. The Atlantic would rise up, up over our driveways, up over our decorative bushes and front steps, up over our decks and railings, up over the windows and the roof gables, until all of our coastal homes disappeared beneath the flat blue surface of the sea, where clouds would skate and bloom as though nothing and no one had ever existed below.

I drive past the high-rises currently under construction, with breezy names like Aria on the Bay, One Paraiso, and Solitair. Past two Lamborghinis, two Ferraris, one Rolls-Royce, and one brand-new Bentley with a matte white coat of paint and chrome hubcaps. Past the port where six cruise ships pause. Past a string of coin-sized islands covered in not-so-coin-sized houses: Star and Fisher, Belle and Hibiscus, San Marco and Rivo Alto. And as I pass, I imagine all of it underwater.

Past the new Pérez Art Museum, which already sits on 15-foot stilts as a safeguard against higher tides, stronger storms, and severe flooding. Past the Crescent Heights Inspirational Living construction site on the corner of Alton Road and Sixth Street—the intersection that flooded twice in 2000, four times in 2010, and eight times in 2013. Past the floodwater pumps and the street-elevation projects meant to serve the imagined residents of the “Wave,” the name Crescent Heights Inspirational Living gave its new development. Past CVS, Walgreens, H&M, and Forever 21. Past Petco Animal Supplies and Wet Willie’s cocktail lounge. Past the South Seas Hotel and Eden Roc, the Shore Club and the Ritz. Past a couple with sun hats and beach chairs and a dachshund.

In my mind there is no tidal wave and no wreckage. Instead everything is simply, coolly covered by blue.

I am ashamed to say that, when I finally reach the Cox Science Building, I sit in my rented Toyota Yaris and feel something close to smug. I imagine this is how the Oracle of Delphi felt divining the future from a fistful of smoke. “Love of money, nothing else, will ruin Sparta,” she said to Lycurgus. Yes, I think, love of money, nothing else, will ruin Miami.

But then I remember that water is not discerning. It doesn’t know the difference between a millionaire and the person who repairs the millionaire’s yacht. The thought stops me in my self-righteous tracks.

I once heard Katie Ford read from a book of poems she wrote after Hurricane Katrina. She said—in a voice I understood as God’s voice on the night the water arrived in the city:

What do you expect me to do

I am not human

I gave you each other

so save each other.

That night the moon is big and full, making the ocean weightier. The salt water unspools in the streets and continues drowning, by degrees, the low-lying land that lines our shore. Soon, I think, if Hal is right, all of this will be underwater, not just temporarily, but for good. In the meantime, in Miami Beach the water pumps whir, while five miles north of here there is a barefoot woman who carries her sandals in her hands, wades through the all of it that is always now rising.