California Governor Jerry Brown has long been calling for drastic action on climate change, which he has called an “existential threat” to the state, the country, and the world. And as the Trump administration has scaled back national efforts for climate action, the leader of the nation’s most populous state has become increasingly influential.

“Given the absence of leadership in Washington,” Brown told CalMatters in 2017, “the mantle of leadership falls on California, and we won’t shirk it.”

The Golden State has indeed fought hard to preserve its aggressive programs to control pollution, reduce demand for fossil fuels, and fulfill its pledges under the Paris Agreement. And as the world’s sixth largest economy, California has the potential to serve as a climate model for other states and nations alike.

But a new report out today from a coalition of environmental advocacy groups details one major oversight in California’s climate policies that could undermine its climate efforts: oil production.

Given all the attention to Brown’s environmental advocacy, it’s easy to forget that California is an oil state. Indeed, California is second only to Texas in the amount of oil extracted since 1900, and California crude is some of the dirtiest oil on the planet; much of what remains in the state’s reserves is thick as peanut butter, and energy intensive to both extract and refine.

While research shows that any expansion of oil production would exceed the planet’s carbon budget—the amount of greenhouse gases that nations around the globe can emit and still keep temperature increases below two degrees Celsius—California continues to issue new drilling permits. During Brown’s tenure, permit approvals by the state’s Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources reached a 30-year peak in 2015. Over the course of his administration, DOGGR has issued nearly 20,000 well permits.

Moreover, California’s oil industry is not as well-regulated as some might think. California is one of a minority of oil states with no legally mandated buffer zone between structures like homes, schools, or hospitals and active oil and gas wells. Fourteen percent of the population—some 5.4 million people—live within a mile of a well. And it’s one of only two states in the nation without a production or severance tax on the oil and gas industry—a “de facto subsidy” for the fossil fuel industry, according to the report.

These fossil-friendly policies could effectively cancel out the benefits of the state’s bold commitments to reduce oil consumption. For example, Brown pledged to cut oil use in vehicles by 50 percent over the next 12 years, which would save about 430 million barrels of oil. But business-as-usual permitting in California could lead to the production of an additional 560 million barrels of oil over the same time period.

“We need to keep dirty fossil fuels in the ground to avert climate and health catastrophe, but California continues to hand out new drilling permits like candy,” Kassie Siegel, the director of the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Institute, which endorsed the report, said in a statement. “This devil-may-care approach to oil extraction threatens to sabotage not just our state’s climate progress, but the world’s. That’s why we’re demanding Governor Brown halt new drilling in California and create a just transition plan to phase it out as soon as possible.”

The report calls on California to stop issuing permits for new extraction wells and implement a 2,500-foot buffer zone around existing wells, which would shut down about 8,500 active wells.

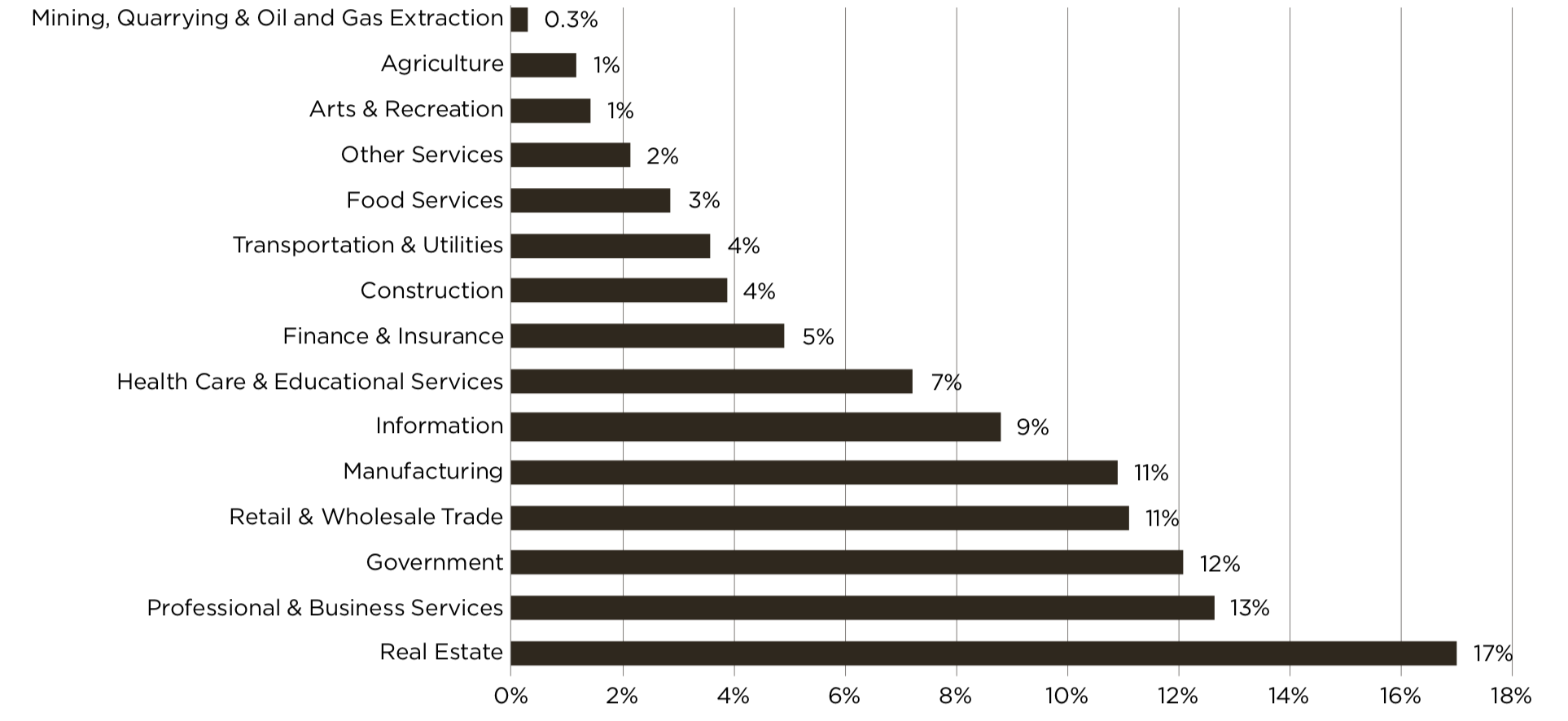

Wealthy oil producers like California not only have an “urgent responsibility” to lead the way on phasing out fossil fuel extraction, according to the authors, but the state is also uniquely positioned to do so. For one thing, California’s oil industry has been declining. As of 2017, mining in general, which includes oil and gas extraction, accounted for less than 0.3 percent of the state’s gross domestic product. In 2012, nearly 23,000 people worked in oil extraction in the state; as of 2017, that number had fallen to 14,500.

(Source: Oil Change International)

The report’s analysis finds that a 5 to 10 percent tax on oil production, which the authors call a “Just Transition Fee,” could generate enough revenue to cover up to five years of wages for those workers, plus four years of college tuition, and still have $2 billion left over.