In America today, the average white family currently holds almost seven times the wealth of the average African-American family, and five times the wealth of the average Hispanic family. This disparity is nothing new: The racial wealth gap hasn’t changed in 50 years, despite decades of policies aimed at reducing discrimination in the labor market and improving African Americans’ access to higher education.

The causes behind this wealth gap, while not simple, are clear: Centuries of slavery, segregation, and government-sanctioned discrimination dramatically curtailed African-American families’ ability to amass wealth and pass it along to their children. All the while, white families were slowly accumulating wealth, thanks in part to government policies designed to help them afford college tuition and a home mortgage, and to later pass such benefits on to their children. As William Darity, a professor at Duke University, told me last month, “[t]hese inequalities are baked into the system through the process of transfers that take place across generations.”

A new report from Rachel Fishman of the New America Foundation, a non-partisan Washington, D.C., think tank, highlights yet another federal government program that’s similarly widening the wealth gap: the Parent PLUS loan program. The Parent PLUS program was created in 1980, its primary goal to help middle-income families pay for college during an era of high interest rates and increasing tuition. The loans, which are not subject to the borrowing limits on other types of college loans, carry a higher interest rate than student loans and are typically used by parents only after other kinds of financial aid and loans (i.e., student loans, federal subsidized and unsubsidized loans, etc.) are tapped out.

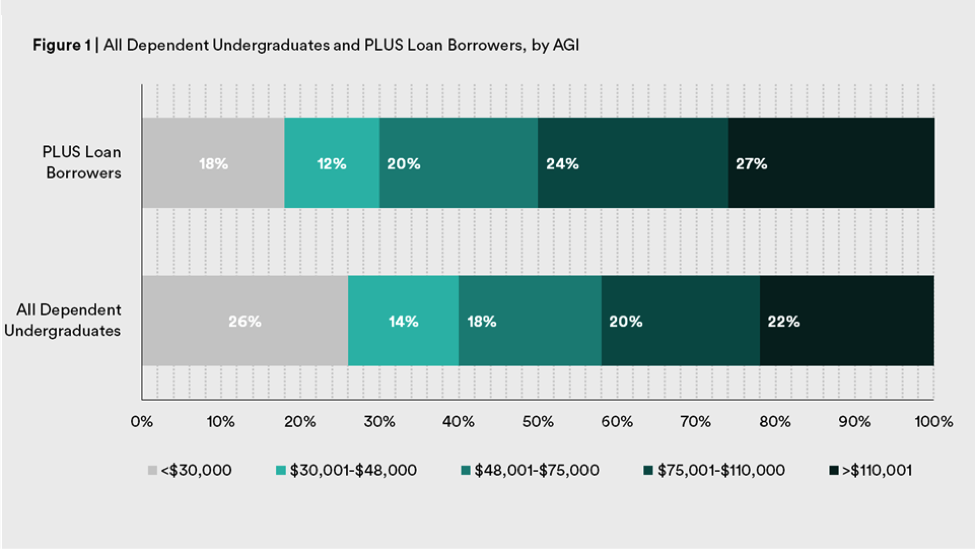

Indeed, the majority of Parent PLUS borrowers fit this profile. As the chart below, from the report, shows, over 50 percent of borrowers in 2012 had a family income over $75,000:

Among white borrowers, the Parent PLUS program appears to work as intended (i.e. as a financing mechanism for wealthier families). Among white families, the share of PLUS borrowers increases alongside income: Only one in 10 white PLUS borrowers in 2012 had a family income less than $30,000, and a third had an income over $110,000. Among black families, however, the opposite is true: a third of black PLUS borrowers in 2012 had an income under $30,000, while one-in-10 had an income over $110,000.

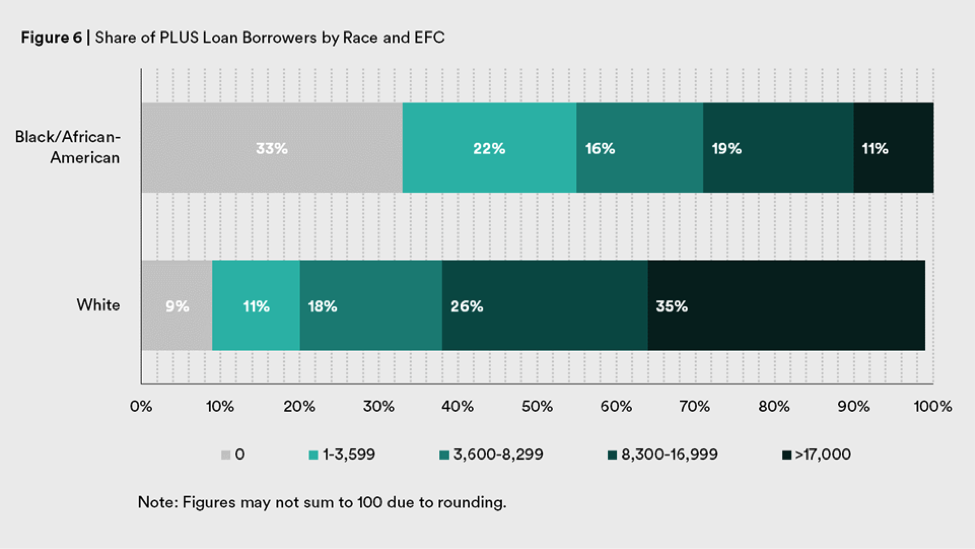

Fishman finds a similar disparity for families with an expected family contribution (EFC) of $0. The EFC, which is calculated when determining eligibility for various forms of financial aid, is meant to indicate how much money a family can contribute to their child’s education. Families with an EFC of $0 are typically quite low-income and, by definition, cannot afford to contribute anything to their children’s education. As Fishman writes, “[a]rguably, no family with a zero EFC should take on a PLUS loan, as EFC is a rough approximation of the ability to repay a loan.”

Nonetheless, as the chart below illustrates, 33 percent of black PLUS borrowers in 2012 came from families with a $0 EFC, compared to only 9 percent of white PLUS borrowers:

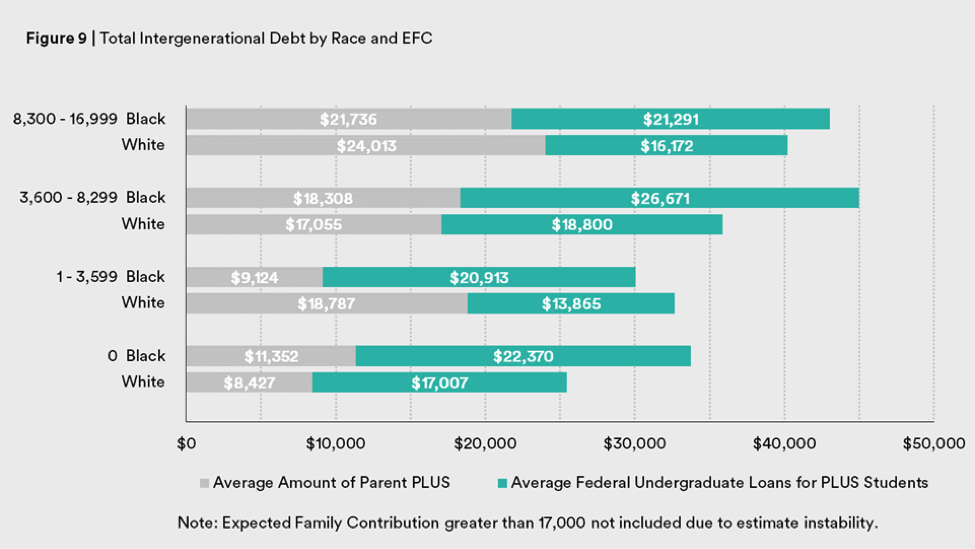

Perhaps not surprisingly, all this borrowing adds up to significant disparities in total family indebtedness, particularly among the poorest families. The chart below illustrates total intergenerational indebtedness:

“Black families with zero EFC accumulated an average of $33,721 in intergenerational debt, of which $11,352 was in PLUS loans,” Fishman concludes. “By contrast, white families with zero EFC accumulated $25,434 in debt, 25 percent less. Even among families that the EFC formula judges equally needy, debt outcomes for white and Black families are very different.”

So how, in Fishman’s words, did the Parent PLUS loan program go so far off the rails and “end up serving exactly who it was meant to for white families but not families of color, especially Black families?” Fishman points to all the usual known drivers of the racial wealth gap—discriminatory housing policies, labor market discrimination, etc.—that have put African-American families in the difficult situation of having few other options for funding their children’s education, but she makes another point as well: America’s retreat from public financing for higher education has disproportionately harmed African-American families.

As Sara Goldrick-Rab documented in exhaustive and devastating detail in her 2016 book, the federal financial aid system has simply failed to keep up with the demand for, and cost of, higher education. Pell grants, which were created to allow low-income Americans to go to college without wracking up tons of debt, no longer cover even community college tuition in many places, let alone living expenses or the tuition costs at more expensive institutions. Public institutions of higher education, meanwhile, have responded to education funding cuts by increasing tuition. These trends, while painful for middle-class white families as well, have been disastrous for black families with much less familial wealth to draw on.

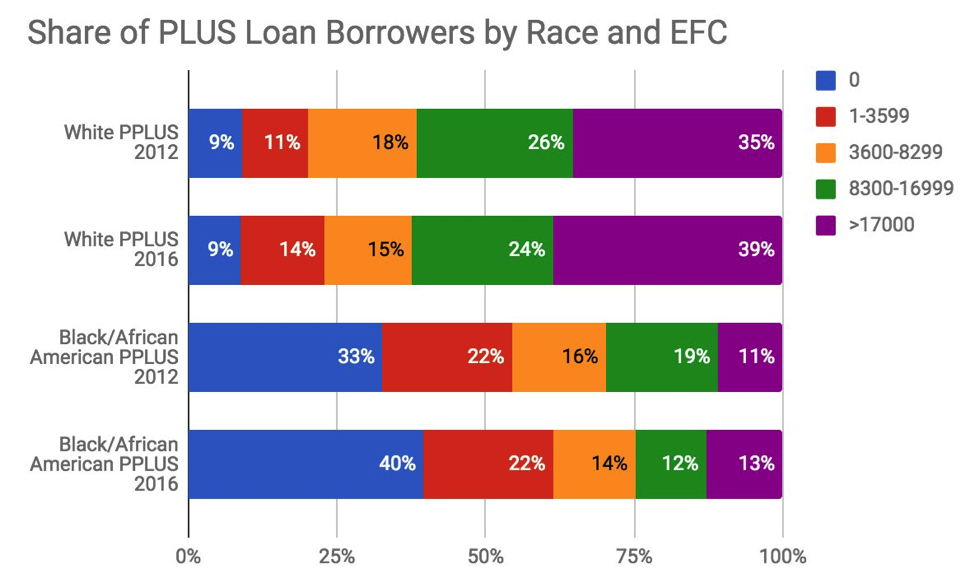

The chart below, which Fishman recently posted on Twitter and which contains new data, illustrates the change in the share of white and black PLUS borrowers, at various EFC levels, between 2012 and 2016:

Fishman’s findings are all the more concerning in light of the ample body of evidence concluding that black students are much more likely to struggle to repay back their student loans. In a report for the Brookings Institution, the researcher Judith Scott-Clayton projected that 70 percent of black student borrowers may ultimately default on their loans and concluded that “[d]ebt and default among black college students is at crisis levels.”

Fishman’s report proposes a number of feasible, short-term reforms to the PLUS program—things like improving counseling, disclosure, and servicing procedures around the loans—but she ultimately concludes that a true fix must be much bigger.

“The federal government’s role in higher education is important, and it already provides grants and loans to help students afford it, but that is not enough,” Fishman writes. “In order to provide true access for low-wealth families, there must be a targeted investment that is not debt-financed and will completely bring down the cost of, at a minimum, public two- and four-year universities while holding institutions accountable for that investment.”