The town of Lowell, Massachusetts, is notable for having successfully navigated a number of economic reincarnations. For much of the 1800s and the first half of the 1900s, Lowell, which straddles the Merrimack River and sits about 30 miles northeast of Boston, was home to a thriving textile industry. With its five-story mills lining the Merrimack and sophisticated canal system, Lowell served as a shining example of urbanization; Massachusetts Governor Edward Everett once wrote that the city’s growth “seems more the work of enchantment than the regular process of human agency.”

When the city’s textile industry failed after World War II, Lowell successfully reinvented itself as a regional technology hub, home to (most notably) Wang Laboratories. But with the bankruptcy of Wang in 1992, Lowell set about reincarnating itself once again, transforming its old textile mills and abandoned Wang facilities into affordable housing and corporate office space. The Lowell Development and Financial Corporation provided low-interest loans to local business owners, many of them drawn from the local immigrant and refugee communities. City leaders also worked hard to invest in and leverage the assets of Lowell’s sizable population of Cambodian refugees, offering ESL classes, providing technical assistance to non-profits serving the community, and encouraging the development of events like the Southeast Asian Water Festival.

As a result of these initiatives, Lowell not only successfully recovered economically but actually became more racially and economically inclusive during its recovery. Between 1990 and 2000, there were decreases to residential segregation, the proportion of the population classified as rent-burdened, and racial home ownership and education gaps.

Lowell’s story of racially and economically inclusive growth and recovery runs counter to that of the country at large after the Great Recession. In the United States, recovery has been slow and uneven—some cities bounced back quickly, others are still struggling. It has also been defined by stagnant wages. In many of the cities that recovered most quickly—New York and San Francisco, for example—the combination of a skyrocketing cost of living and wage stagnation have produced severe economic burdens for all but the wealthiest residents. This paradox raises an important question: Can economic recovery and increasing inclusivity go hand-in-hand?

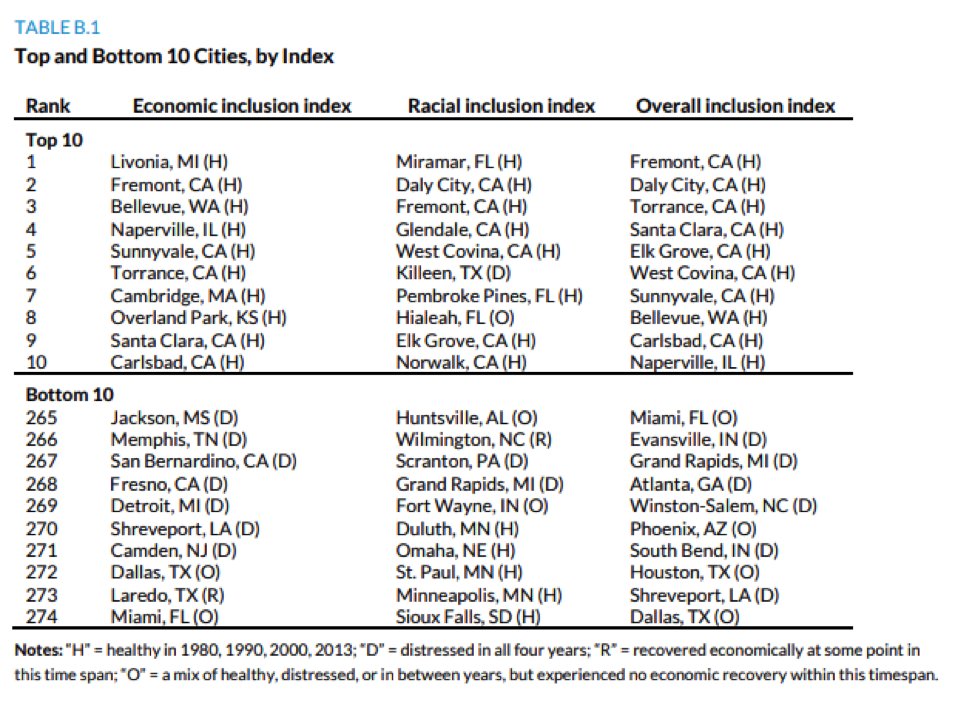

This question is the topic of an interesting new report and data tool from the Urban Institute, a non-partisan think tank. The report measures both economic and racial inclusivity in 274 cities across the country, identifying the most and least inclusive cities in the country (the data tool allow users to search for their own cities as well). As the chart below illustrates, the most inclusive cities are often small- and mid-sized cities:

The researchers also used this new data set to study past economic recoveries (back to 1980) and identify cities that underwent economic recoveries while also improving on measures of racial and economic inclusiveness. The goal, says Erika Poethig, an Urban Institute researcher and co-author of the report, is to inspire leaders to view periods of economic recovery as opportunities for needed change. Poethig also served as an acting assistant secretary at the Department of Housing and Urban Development during the Obama administration.

“The research is really inspired by the idea of being optimistic about places that are more distressed today,” Poethig says. “And imagining that, as we work through this recovery process, we can make intentional decisions to move the dial on both economic and racial inclusion.”

Relying on case studies of Lowell and three other cities—Columbus, Ohio; Louisville, Kentucky; and Midland, Texas—Poethig and her colleagues identified eight common characteristics of inclusive economic recoveries: the adoption of a shared vision, bold public leadership, cross-sectoral partnerships, a process that builds voice and power even for historically marginalized communities, the identification and leveraging of existing assets, a regional mindset, the reframing of inclusion as integral to growth, and the adoption of policies that specifically support inclusion.

In other words, investing in priorities like affordable housing, education and training, and community development can actually help drive an economic recovery forward.

“There’s no question these can be counterintuitive decisions to make when resources are constrained,” Poethig says. “But one of your biggest assets is the human capital that lives in your city—investing in your diverse communities can really drive economic growth.”

It’s a sentiment that many U.S. policymakers—at both the national and local levels—have thus far ignored.