This story was produced in collaboration with the Guardian and Documented.

The Texas hornshell is a sleek green-gray mussel that once thrived in the Rio Grande watershed, its habitat stretching from southern New Mexico down into the arid Texas borderlands. Some of its habitat happens to overlap with rich deposits of oil and gas.

Amid a long-term decline in its range, the Obama administration in 2016 proposed to declare the mussel an endangered species. Upon taking office, however, the Trump administration changed tack.

A top official at the Department of the Interior (DOI), Vincent DeVito, appears to take credit for helping to delay federal protections for the species at the behest of fossil fuel industry groups, one of several examples of his willingness to prioritize the needs of extractive industries with business before the government, according to public records obtained by the Guardian and Pacific Standard as well as Documented and the Western Values Project, both watchdog groups.

DeVito, a Boston energy lawyer and the former co-chair of Donald Trump‘s presidential campaign in Massachusetts, is a little-known figure in the United States government. He is one of a host of political appointees hired by Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke, whose department oversees well over 400 million acres of public land and can determine the fate of the species that inhabit them.

Yet DeVito is now emerging as a critical player. At a speech last summer to Americans for Prosperity, a political advocacy group backed by the Koch brothers, DeVito described his role at the department as “the office of energy dominance.” Officially, there is no such office, though “energy dominance” has become a slogan for the Department of the Interior’s fossil fuel-first policy agenda.

“The war on American energy is over,” DeVito told the activists, according to a recording of the speech obtained by Pacific Standard. “And, matter-of-fact, if there is a war, we’re going to win it and we’re going full bore,” he said, before adding that the administration’s approach would be a “responsible” one.

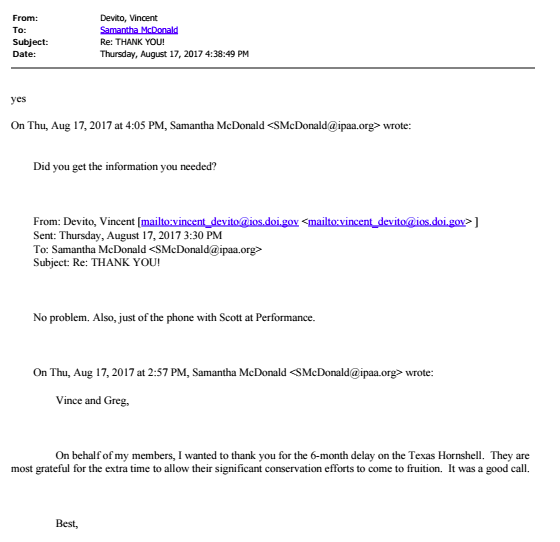

Matters for the Texas hornshell case came to a head in June of 2017, when the Independent Petroleum Association of America, an industry trade group, met with DOI officials, including both Zinke and DeVito. Two weeks later an IPAA staffer emailed DeVito to ask that the species listing be delayed for six months, citing industry opposition.

“We really hope that you can intervene before this species gets listed next month,” Samantha McDonald, the IPAA’s government relations director, wrote to DeVito. In his reply, DeVito asked that McDonald keep him apprised of “what you may be hearing as this unfolds.”

Less than a month later, in August, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service granted the delay that IPAA sought. McDonald again wrote DeVito, as well as the acting director of the fish and wildlife service, in an email with the subject line “THANK YOU!”

“On behalf of my members, I wanted to thank you for the six-month delay on the Texas Hornshell,” she wrote, adding that it was “a good call.”

DeVito responded to McDonald that same day. “No problem,” he wrote.

Although the mussel was eventually granted protections in February of 2018, former DOI officials with knowledge of the department’s rules and procedures say DeVito’s apparent involvement in the listing process raises both ethical and legal questions.

“Listing decisions under the Endangered Species Act are meant to be entirely science-based decisions that result from—in some cases—years of review by experts in the field, not political appointees,” says Elizabeth Klein, a former associate deputy secretary at the DOI during the Obama years and now the deputy director of New York University’s state energy and environmental impact center.

“A delay in and of itself might not be the end of the world—but then again it very well could be for an imperiled species.”

Charles Randklev, a research scientist at Texas A&M’s Natural Resources Institute who has closely studied the hornshell, says the species is “standing on the brink.”

“We were all taken by surprise,” he says of the listing delay.

In a statement, the DOI press secretary, Heather Swift, said that DeVito “disagrees with [Pacific Standard‘s] analysis of the emails.”

DeVito “maintains that he simply responded with an acknowledgement of receipt on the mussel email and maintains he had no role whatsoever in the listing,” Swift said.

Referencing comments by Zinke, she noted: “Political appointees are not at the department to manipulate data, they are here to make informed decisions and policy.”

DeVito’s penchant for “energy dominance” has played out in other ways as well. As chairman of the DOI’s royalty policy committee, he helps determine the royalty rates that energy companies must pay to drill and mine on federal lands and waters, effectively encouraging or disincentivizing them.

(Photo: New Mexico State Land Office)

At his Americans for Prosperity speech, DeVito described how he consulted closely with fossil fuel groups before recommending to Zinke in February that the DOI reduce royalty rates on offshore oil and gas drillers by a third, from 18.75 percent to 12.5 percent.

Ultimately, Zinke rejected that proposed reduction, but DeVito’s committee and its affiliated working groups labored to deliver on other industry desires as well, including drafting proposals to roll back regulations.

DeVito’s energy agenda also took him to West Virginia last year, where he helped coal interests obtain federal approval for a new mine near the habitat of Appalachia’s imperiled Big Sandy crayfish.

“Mining is the single biggest factor that has eliminated this species from a lot of its range,” says Roger Thoma, a senior research associate at the Midwest Biodiversity Institute who has surveyed the crayfish extensively.

In 2016, the Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Big Sandy crayfish as threatened, meaning new coal mines are required to consult with FWS before initiating projects that might prove harmful. One such project was the Berwind mine, an underground coal operation in the southern West Virginia owned by the company Ramaco Resources, several of whose board members are major Trump campaign contributors.

As the Fish and Wildlife Service deliberated through 2016 and early 2017 over how best Berwind and other mines might mitigate potential harm to the crayfish, the industry chafed at the wait. “That is a long time to have multi-million-dollar mine project investments that would employ hundreds pending” due to uncertainty around crayfish protection standards, says West Virginia Coal Association vice president Jason Bostic.

(Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

On June 14th and 15th last year, DeVito traveled to West Virginia and came to the industry’s aid. According to records, his trip was planned in part by the West Virginia Coal Association itself, which submitted a trip schedule to one of DeVito’s colleagues. The schedule included meetings with the coal association as well as both state and FWS regulators overseeing crayfish conservation in the region.

Four days after DeVito’s trip, the Fish and Wildlife service approved the Berwind mine’s protection plan for the crayfish. In his speech to Americans for Prosperity, DeVito highlighted his role in enabling the mine’s approval.

He loved “fixing small problems the best,” he told the crowd, “because if I go out to West Virginia and I rescue a coal project from bureaucratic entanglement, and then you see two days later the company in the field with guys going back to work, that is pretty rewarding.”

Conservationists, however, say the DOI’s decision to approve the Berwind mine’s crayfish protection plan was deeply flawed.

Such plans “are supposed to be these very thorough documents … about how mining operators will protect the species,” says Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, which sued in 2012 to have the Big Sandy crayfish listed under the Endangered Species Act. “This one is short, and doesn’t go into detail. It is woefully inadequate.”

While intervening in crayfish matters, meanwhile, DeVito went even further, and added his signature in red pen to a plan that guides regulatory scrutiny of future mines operating in or near crayfish habitat. Former DOI officials familiar with FWS rules and regulations say that a lawyer and political appointee like DeVito has neither the scientific expertise nor the authority to approve such science-based guidance.

“It is a scientific integrity violation for a political appointee to essentially leapfrog the Fish and Wildlife Service’s process when you have an Endangered Species Act listing involved,” says Joel Clement, a long-time scientist at the Department of the Interior and now whistleblower who left the department after being pushed out of his post.

“It is absolutely inappropriate. As a senior adviser [DeVito] has no authority of position—so essentially that guidance was not worth the paper it was written on.” Nevertheless, the guidance DeVito signed appeared to remain in effect for nine months, until state and federal regulators updated and approved a more stringent version in late March.

In the end, DeVito’s trip to West Virginia helped feed a broader narrative that Trump has promoted.

Less than two months after the trip, Trump arrived in West Virginia too, where he held a boisterous political rally.

“As president,” Trump said to his adoring crowd, “we are putting our coal miners back to work.”

This story is published in collaboration with the Guardian as part of its two-year series, This Land Is Your Land, with support from the Society of Environmental Journalists.