Last Wednesday, we commemorated the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. On the same day, we witnessed the killing of Saheed Vassell, another unarmed black man, this time by New York City cops.

This week marks 50 years since the passage of the Civil Rights Act, which bars housing discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, or sex.

But residential segregation is still very much alive: In Chicago, where I live, 23 neighborhoods clustered on the city’s South and West sides are more than 80 percent black, even though black people make up just a third of the city’s population. Where residential segregation persists, so does educational segregation.

Five decades after his martyrdom, most white Americans have come around to some soft-focus idea of King himself—but not necessarily to integration on the block or in the classroom. These days, though, segregation is usually remembered as something others did, as though it was a minority of cross-burning thugs—a few bad apples—who were Jim Crow’s toughest defenders.

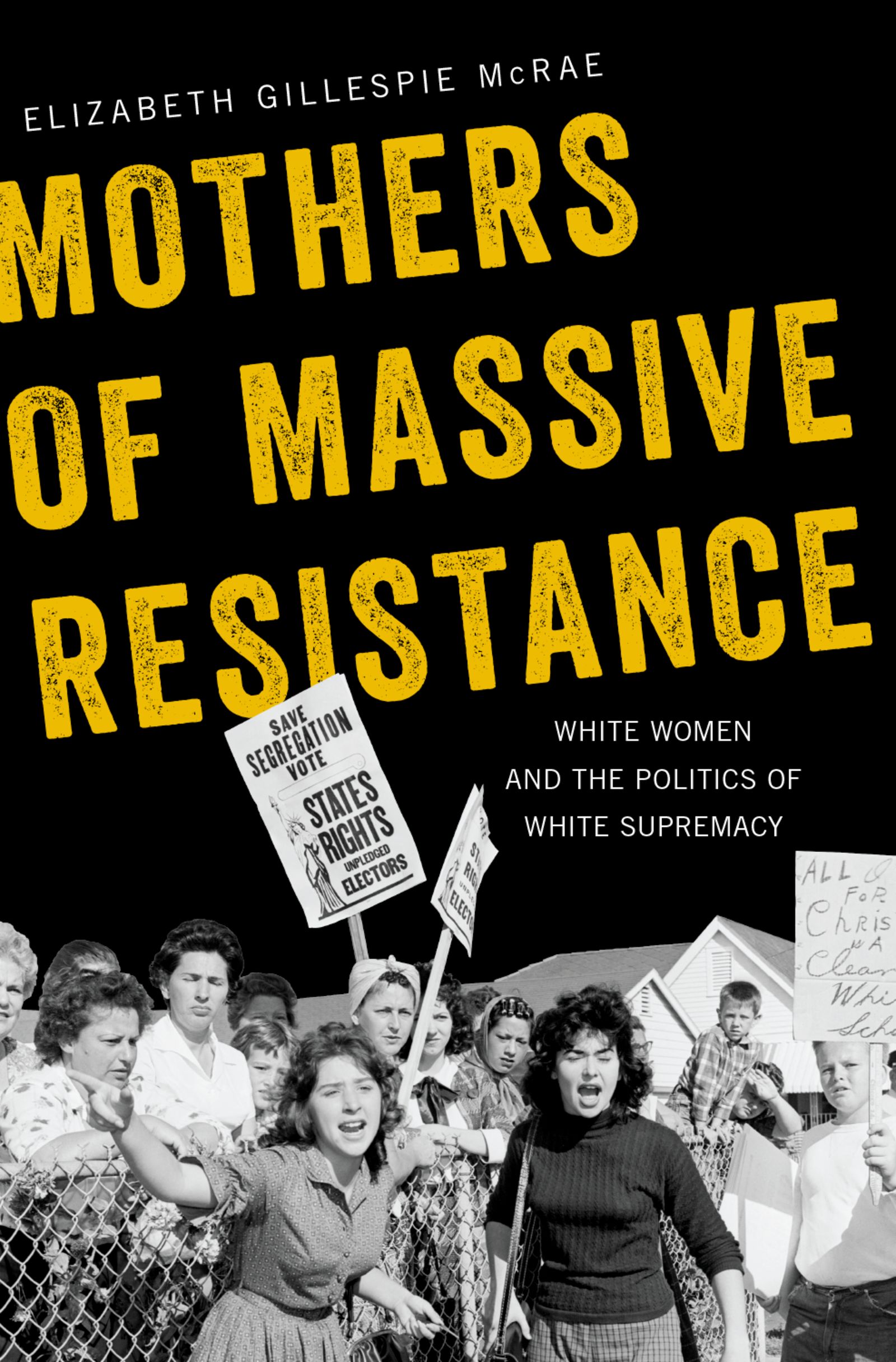

Recently published by Oxford University Press, Elizabeth Gillespie McRae’s Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy takes a sharp look at mainstream, everyday segregationism: the segregationism of respectable white women. How, McRae asks, did those white women work to maintain segregation across the 20th century? What was their role in the battle to preserve Jim Crow? Why do many still support racist policies and politicians?

Unlike governors or legislators, white women couldn’t directly enforce Jim Crow with state power. Unlike the Klan, they generally eschewed direct violence. Their sphere of authority was family, home, and those local spaces considered extensions of the domestic sphere—most notably public schools. Their work was daily, grassroots, and rarely glamorous. White women, McRae writes, were “segregation’s constant gardeners.”

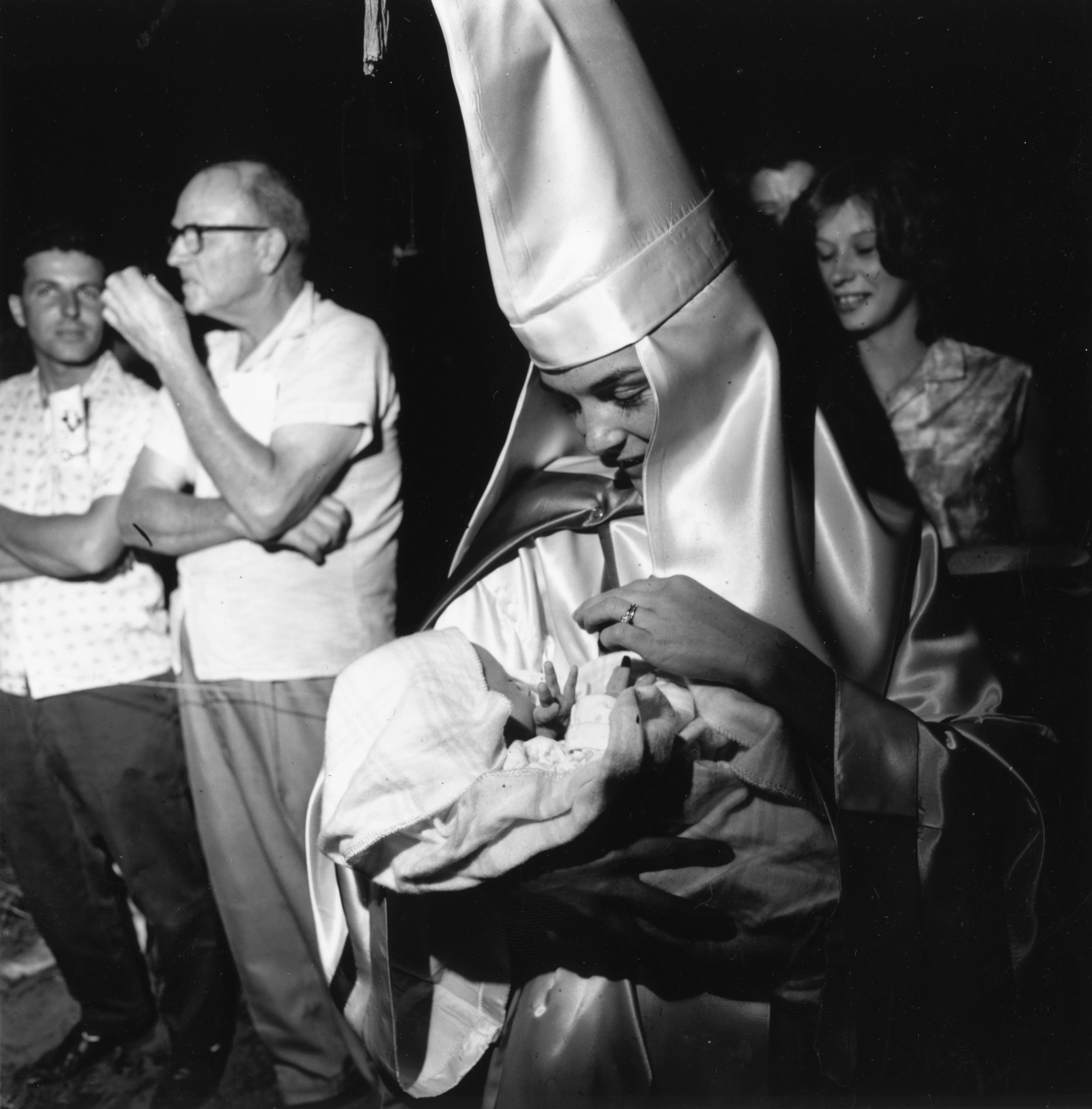

Good white women, and especially good white mothers, “married gender roles [with a] devotion to racial segregation.” They had a special obligation to police the color line where public and private life intersected: Midwives classified the race of the babies they helped bring into the world; public school teachers plucked students suspected of being mixed-race from their classrooms. Some educated women nourished the illusion of a more “affectionate segregation,” in columns containing fond tales of their housemaids and childhood mammies.

(Photo: Oxford University Press)

White women’s work to maintain a segregated America extended much further than we tend to believe, in both time and space. That work wasn’t confined to the years between Brown v. Board of Education and the Voting Rights Act; rather, McRae argues that it started in the 1920s, when white women employed as teachers, registrars, social workers, and midwives began to engage in the waged labor of racial classification, and it continues today.

Massive resistance—the wave of legislative, legal, and public protests against integration—is usually seen as a Southern project. Not true, McRae counters: In fact, white segregationist women in the South built alliances and shared strategies with women from California to Michigan who were also seeking to maintain white supremacy in their communities.

As McRae demonstrates persuasively, white women’s efforts accounted for the “endurance and shape-shifting capabilities of white resistance,” which kept segregation in place even as judicial and legislative victories seemingly cleared the way for racial equality.

McRae’s book is an excellent history of white women’s politics generally, but it’s especially strong as a history of white women acting to protect “their” public schools. The women McRae writes about insisted that their concerns about integration were not racist. Instead, they invoked their identity as mothers to elevate their supposedly moral opposition to integration, and to distinguish themselves from open bigots. Some of them used baby strollers to block buses that were meant to take children to integrated schools.

These mothers also spoke of their rights as property owners. McRae cites a 1972 New York Times article, in which working-class whites emphasized the struggle and sacrifice that let them “buy homes in good school districts which would make the American Dream possible for their children.” Bussing, McRae writes, “threatened to erode that dream and to violate their rights as property owners.”

Compare that to the complaint of a St. Louis parent in 2013, six decades after Brown v. Board of Education. That year, Missouri offered students from the nearly all-black Normandy school district—so poorly performing it lost state accreditation—the chance to transfer into the nearby Francis Howell district, which is 85 percent white. At a public meeting, a mother of three argued against the proposed integration: “I shopped for a school district. I deserve to not have to worry about my children getting stabbed, or taking a drug, or getting robbed.”

McRae reminds us that opposition to bussing was often couched in the race-neutral language of school choice. In the midst of a 1972 “mothers’ march” protesting bussing, Irene McCabe, the leader of the anti-bussing National Action Group in Pontiac, Michigan, insisted that she wasn’t opposed to integration—just, as she told a reporter, to “the long arm of the federal government reaching into my home and controlling the children I gave birth to.”

(Photo: Harry Benson/Getty Images)

Now, as then, ostensibly race-neutral policies like “school choice” can conserve a segregated status quo. The Century Foundation, a non-partisan think tank, has found that, “On balance, voucher programs are more likely to increase school segregation than to promote integration or maintain the status quo.” More than 1,000 of the nation’s 6,747 charter schools have over 99 percent minority enrollment, AP reports.

Knowing this history is key to detecting the bad faith of what McRae describes as “color-blind conservatism … that disguised policies supporting racial inequality behind the language of property rights, law and order, good motherhood, and constitutional intent.” This form of politics is still troublingly influential. Secretary of Education and “proud mother, grandmother, and wife” Betsy DeVos is one of the country’s most vocal proponents of school choice—and she seemingly betrayed the segregationist bent to her policies when she described historically black colleges and universities as “pioneers” in the movement for choice.

McRae’s project fulfills nearly all the requirements for a feminist history. She uncovers the role women played in a well-known historical movement, in which powerful or violent men—Klan members or George Wallace—are usually assigned the lead. She shines a light on their under-recognized, feminized work to shape and support that movement. She even demonstrates how women responded to gendered and class-based limitations on their power to perpetuate segregation in the public sphere with creativity and resilience.

The New Orleans “cheerleaders,” a group of mothers protesting integration of an elementary school, “knew they lacked political capital” because they were female and working-class. They fought desegregation in the ways available to them: with taunts, harassment in the streets, phone calls to integrationist employers, and by weaponizing their own children, whom they encouraged to bully former classmates who now attended desegregated schools.

The history that McRae lays out is something any contemporary feminist would be ashamed to own, of course. These women are not on the right side of history, as women tend to be in most feminist narratives. There is no sense of essential female goodness. Their gender—and by extension, their familiarity with oppression—does not keep them from becoming oppressors.

“The grassroots politics of massive resistance was also a women’s movement,” McRae argues, though one distinct from the liberal feminist women’s movement. In McRae’s account, white segregationist women were alienated by liberal feminism’s refusal to embrace “women’s issues” that were also issues of white supremacy, like an opposition to bussing. Instead, McRae shows, pro-segregation women found a political home in the emerging New Right, among conservative politicians who continued to reify traditional notions of white womanhood and white motherhood.

Many white women continue to choose to spend their political capital on men with racist, misogynistic track records, rather than on promoting the liberal conception of women’s rights. A majority of white women gave Donald Trump their vote, even though he was caught on tape bragging about grabbing women “by the pussy.” In Alabama’s special election this December, more than two-thirds of white women went to the polls for Roy Moore, a man credibly accused of sexually assaulting teenage girls.

It is easy to stand in judgment of dead bigots. It is more difficult, and does more justice to this history, to begin to interrogate our own politics, our own bigotry, and our own quietly racialized defenses of social and economic relationships—especially around property rights—that are ultimately incompatible with racial equality.

By the 1970s, McRae writes, few white women were willing to acknowledge their racism, even as they worked for a politics of white supremacy. On some level, a lot of present-day whites—like those women—are aware that racial equality represents a threat to a measure of our own comfort and security. What we don’t have is a sobering sense of our own place in history, of how clear it will likely be to future generations that, when it came time to choose between our anti-racism and our socio-economic power, we had already made the decision long ago.

The women McRae writes about were aware that what they had was tenuous and dependent on racial inequity. It’s impossible to dismiss them: They look too much like us.