Xenophobic rhetoric may actually target American citizens more than immigrant communities.

A new study published in the journal Social Science & Medicine shows that anti-immigrant prejudice is associated with higher mortality rates among non-white American citizens.

After spending years listening to anti-immigrant rhetoric from politicians, lead researcher Brittany Morey, a postdoctoral fellow at University of California–Riverside, wanted to examine the effect of this charged rhetoric on the health of immigrant communities and American-born people of color.

The study, performed by researchers from the University of California–Los Angeles Fielding School of Public Health and the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, examines data from the General Social Survey, an assessment conducted every two years to gauge American public opinion toward a range of social issues, including immigration. The researchers then compare this data with mortality rates in the chosen communities to examine whether anti-immigrant sentiments affect mortality rates among members of those communities.

Among other questions, the GSS survey asked respondents to rate on a scale from one to five their agreement or disagreement with statements such as:

- “America should take stronger measures to exclude illegal immigrants.”

- “Immigrants take jobs away from people who were born in America.”

- “Immigrants increase crime rates.”

- “Immigrants are generally good for America’s economy.”

The final sample of the study included 3,242 respondents living in 123 communities. The sample also took into account respondents’ race and whether they had been born in or outside the United States. Its racial breakdown was 79 percent white, 14 percent black, and 8 percent “other race,” with 47 percent of “other race” respondents born in the U.S. and 53 percent born in foreign countries.

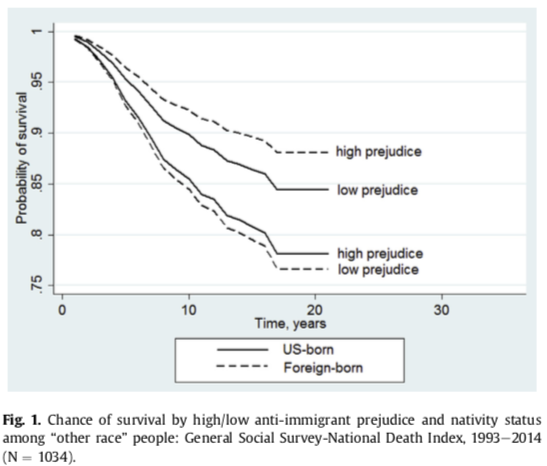

(Chart: Social Science & Medicine)

The study finds that living in a community that demonstrates significant anti-immigrant prejudice does not seem to affect the mortality rates of immigrants as a whole. However, a more nuanced look at the data reveals that non-white (characterized in the survey as “other race”) U.S. citizens have increased mortality risk in communities with high anti-immigrant prejudice.

“It was surprising to me that those who were U.S. born were the ones who were most negatively affected [by anti-immigrant prejudice], even though they’re not immigrants themselves,” Morey says.

The researchers posit that this may be because people born in the U.S. could likely have spent more of their lives in the U.S. and thus had more exposure to racial bias, or that immigrants to the U.S. often form closely knit communities and may interact less with the general population.

“Moving forward, we need to examine how political rhetoric and policies currently under consideration have affected not only immigrants but the people who are already living here—including U.S.-born children,” Morey says.