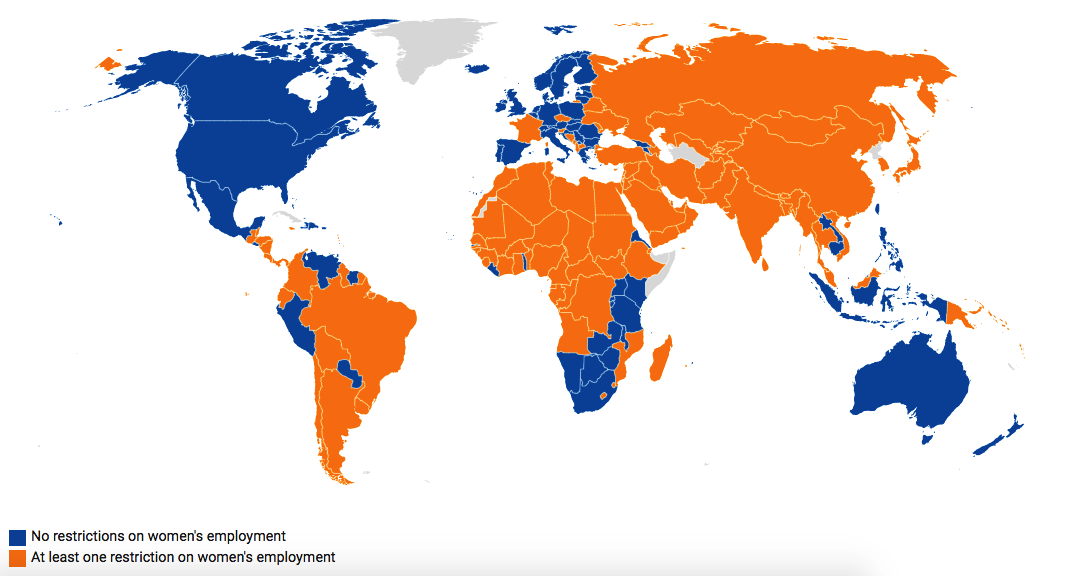

Around the World, 167 countries have at least one law on the books that restricts women’s economic opportunity, a new study from the World Bank has found.

The Women, Business and the Law report measures how legislation in 189 countries affects women’s access to jobs, property, justice, and credit, as well as provisions to protect them from violence and discrimination.

While the proportion of countries with discriminatory laws remained more or less the same since the last survey—88 percent of countries surveyed this time had at least one restrictive law compared to 89 percent in 2016—the report found there had been 87 legal reforms made in 65 countries to increase women’s economic opportunities over the past two years.

Since 2016, 28 countries have made it easier for women to get jobs, and 24 lifted restrictions on women building credit.

One of the most striking findings this year is that women in 104 countries are prevented from working in the same way as men—a figure that surprised even the project’s program manager, Sarah Iqbal.

“It was shocking to me that so many economies all around the world restrict women’s work,” she said.

Most Improved Countries

The report cites the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, and Iraq as having made the most progress on legal rights for women in the past two years.

The DRC reformed its family code in July of 2016, giving married women the right to take on work, open bank accounts, and register a business without needing their husband’s permission. The DRC was also one of the countries to remove restrictions on women working at night, as well as introducing a range of anti-discrimination laws.

Kenya brought in legal aid provisions that improve women’s access to justice, and made it easier to build credit—often a barrier for women who want to start their own businesses.

Iraq, the only country in the top five outside sub-Saharan Africa, abolished the need for a woman to bring a male guardian with her to apply for a passport; it also criminalized sexual harassment and outlawed gender discrimination at work.

Work to Do

There is only one nation left—Equatorial Guinea—that requires a woman to have her husband’s permission to sign a contract. But women still need their husband’s permission to get a job in 18 countries.

Seventeen of them prevent women from traveling outside the home in the same way as men, and six restrict women’s ability to travel outside the country—both figures unchanged since 2016.

(Map: Women, Business and the Law Database/World Bank)

A major barrier raised in the report is women’s right to work at night.

Women are prevented from working the same night hours as men in 29 countries, including India, which prohibits them from working in factories between 7 p.m. and 6 a.m. India’s female labor participation rate is one of the lowest in the world at 24 percent. In Sri Lanka, women are not allowed to work after 10 p.m. in the retail sector—a restriction, Iqbal said, that employers aren’t happy with.

“It should be a matter of choice—women should be allowed to get the jobs that they are qualified for,” she said.

Colonial Holdovers

The report notes that many of the most restrictive laws—including those that require a woman to have her husband’s permission to work or restrict the kinds of work a woman can do—come from old European legal codes that were introduced to sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia under colonization.

“The laws are just on the books but policymakers, who are mostly men, don’t realize that they’re holdovers. Because it’s not at the top of anyone’s agenda, it remains,” Iqbal said

This was the case in the DRC, whose original family code was introduced by the Belgians. “It was based on the Napoleonic Code,” Iqbal said. “Married women had the same legal status as children.”

She refers to these laws as “low-hanging fruit” that can often be reformed by making lawmakers aware that they are a hangover from colonization, and that the colonizing nations themselves—such as the United Kingdom, France, and Spain—have already abolished them.

Slow Progress on Property

Of the 87 legal reforms enacted across the world since the last survey, property rights improved in only one country. Ecuador repealed a law that favored husbands’ decisions in cases of disagreement between spouses on marital assets.

A trend that we’ve noticed is that property laws are much slower to change than labor laws and gender-based violence laws,” Iqbal said. “These issues are very slow to change because they affect asset allocation.”

But, she said, that might not be such a bad thing in the long run. “If you reform property law too quickly you can engender a backlash that can work against women’s rights.”

Will #MeToo Make a Difference?

Iqbal is hopeful that, in the wake of the #MeToo movement, we’ll see more progress on laws that protect women from harassment at work in time for the next report in 2020. Today, 59 countries lack laws prohibiting sexual harassment, with Japan the only Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development high-income country not to offer women protection.

“A lot of laws that affect women don’t get enough attention,” she said. “The #MeToo movement has gotten everyone’s attention, and the law can make a difference in this area.”

Iqbal said a big message to take from the report was that every country in the world can do better on women’s equality, pointing to the United States—the only industrialized economy that does not have paid maternity leave—as a prime example.

“Nobody’s perfect, and I think that’s important for us to know. Often people assume that it’s a developed versus developing country issue, but every country could improve on something.”

This article originally appeared on Women’s Advancement Deeply, and you can find the original here. For news coverage and community engagement focused on women’s economic advancement, you can sign up to the Women’s Advancement Deeply email list.