Lupita Hightower is the superintendent of a school district outside Phoenix, Arizona, that’s 82 percent Latino and where 89 percent of kids qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. The Tolleson Elementary School District doesn’t ask families their immigration status, but judging from the concerned calls from teachers and principals, there’s a good number that include undocumented members. Hightower’s staff know that she herself was once undocumented—her parents brought her to the United States when she was in 7th grade—and often ask for her help whenever a student is having a crisis. “I think, a lot of times, the principal feels that I’ll be able to understand and give them hope,” she says.

The day after Donald Trump‘s election, Hightower got on the phone with a 7th-grade boy, an American citizen, who was crying inconsolably because the president’s rhetoric made him think his undocumented parents would be deported. More recently, Hightower spoke with a middle-school girl whose parents had been deported to Mexico. The girl and her siblings didn’t have a guardian; their 21-year-old brother was taking care of them. The girl began cutting herself as a means of coping with the stress. Hightower called a crisis team, to start the process of getting the kids help.

It seems true that she understands them. “I feel their pain,” she says.

Tolleson Elementary’s problems are disturbingly common across the country, according to a new survey from the University of California–Los Angeles. Teachers and administrators from more than 700 schools in 12 states reported to researchers that they’re feeling the effects of the Trump administration’s harsher immigration policies in their classrooms. In recent months, their students seem to have exhibited more emotional and behavioral problems, more school absences, and worse academic performance. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has a policy of not making arrests in “sensitive locations,” such as schools and churches, which means enforcement actions don’t typically occur at schools (although ICE recently made headlines for arresting undocumented parents as they dropped their kids off for the day). But educators report that the stress at home is still hitting their classrooms, hard.

“The additional burden of trying to educate children who are, very often, U.S. citizens, and are living in terror of losing their families, may simply be too much to ask of our schools,” says Patricia Gándara, an educational psychologist who led the survey. Among the schools Gándara and her team analyzed, those with high proportions of students from low-income families, like Tolleson, were especially likely to report dealing with the ripple effects of immigration enforcement. “The ones that struggle the most to close achievement gaps are hit the hardest by this enforcement regime,” she says.

“The calls coming into NEA about immigration have never been higher or more frightening,” says Lily Eskelsen García, president of the National Education Association, a professional group for public-school workers.

Immigrant advocates have long criticized President Barack Obama for his administration’s high number of deportations. But those removals usually happened at the border, according to ICE numbers. The Trump administration has overseen many more so-called “interior” deportations, of people who are already living in the country. Those are much more likely to affect families with children enrolled in American public schools.

The reasons for the behavioral and academic problems that teachers and staff are seeing can be obvious. Children are worried about themselves or their parents, like the students Hightower has had to soothe. There are also myriad other ways immigration enforcement can affect schoolkids. Some of Gándara’s respondents said local workplace raids had put parents out of jobs, throwing families into poverty or forcing older kids to become breadwinners. Hightower, whose district participated in the survey, says she often sees formerly high-achieving students stop trying because they don’t see a future for themselves in America. And it’s not just undocumented students, or the children of undocumented adults, who are affected. Of the 5,400 teachers, principals, and school counselors who answered Gándara and her team’s survey, about 2,000 said kids at their schools whose families aren’t threatened by deportation have nevertheless had their learning affected by their worries for their classmates.

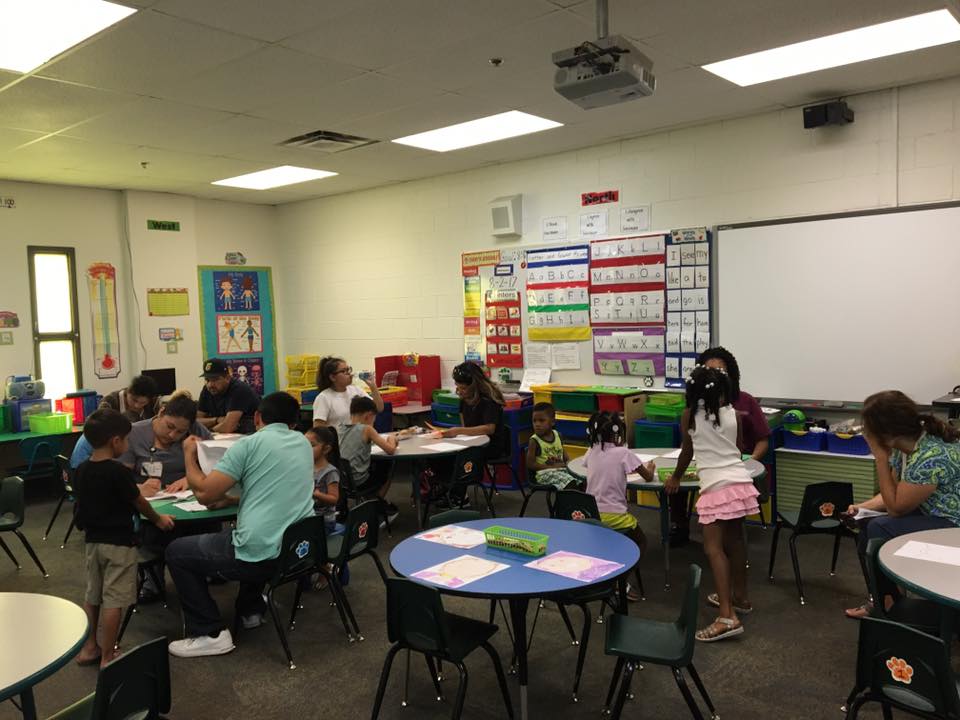

(Photo: Facebook)

“The empty seats that are left in the classroom when these children are taken away are a constant reminder, to everyone, that some of their classmates are missing,” Gándara says. “Both teachers and students can experience grief, as though a classmate has died.”

To help them deal with the stress of the Trump administration’s policies, Gándara’s respondents said they needed more information on what help schools can and cannot legally provide families. They also wanted to see schools hold forums to answer questions and myths churning in communities where ICE is performing immigration raids. The Tolleson Elementary School District holds classes for undocumented parents, clarifying their rights and teaching them how to build safety plans: “Things that the families would need to have if the students would go home and not find the parent,” Hightower says. The classes began last school year, in direct response to the Trump administration.

Hightower had her own ups and downs on her way to her current position, including praise for her teaching skills—former First Lady Laura Bush visited her class—and a University of Arizona professor who told her she would never get a teaching job because of her Spanish accent. She gained legal residency when she married, at age 20, and then later became a citizen. She still shares her experiences to try to motivate kids, when she gets those crisis calls. But in these troubled times, how can she assure them they’ll be OK?

“We try to create the safest atmosphere at the school. If they come to us with those fears, we have to do what we can while we’re at school. That’s what we focus on,” she says. “But I see your point. We don’t know.”