Ask a cop, physician, or EMT in Chicago about July 4th of last year, and most, if not all, will have a story to tell.

The city has a history of violence over this holiday, and police worried that the extra-long weekend in the summer of 2017 would produce exceptionally bloody results. They weren’t wrong.

Over the five-day weekend, 101 Chicagoans were shot; of those, 15 were slain. The holiday drew national headlines and scorn from the Trump administration and others who saw the shooting spree as emblematic of a city intractably stained by violence.

In 2016, 771 people were killed in Chicago, its highest homicide tally since 1996 and the largest number of murder victims by volume of any United States city. Per capita, this wasn’t the highest rate in the nation—it ranked ninth among cities with a population of 250,000 or greater. St. Louis officially held the title of most murderous large city in the U.S. in that year. In 2017, Baltimore—recently declared the most dangerous in America by USA Today and the site of 343 homicides in 2017—is likely to top the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s forthcoming list of most lethal American cities. Baltimore’s police chief was sacked in January due to the rising crime there.

But it’s Chicago that feels like America’s murder capital: The nation’s third-largest city ended 2017 with 650 killings, more than twice the toll in larger New York City or Los Angeles. That represents an improvement over 2016’s numbers, but the sheer scale of the Chicago-style carnage remains striking.

There’s something else that’s extraordinary about Chicago’s murder rate. Take that holiday weekend: While 15 people died, 86 were shot—but survived. They lived because the city’s first responders and emergency room staff have adapted to accommodate combat-zone conditions. Chicago boasts one of the oldest and largest urban emergency medicine networks in the world, with six certified Level 1 trauma centers within the city limits. Indeed, criminologist Arthur Lurigio of Loyola University Chicago credits the strength of this network, and recent improvements in trauma care, with the historic drop in the city’s homicide rate since its mid-1990s peak.

“I have often wondered how many homicides we’d have in Chicago if it wasn’t for the skilled physicians in our ERs,” Lurigio said. “We could very well have surpassed 700, 800, even 900 [murders] into the 2000s.”

The story of why that didn’t happen is a story about what Chicago’s murder statistics can and can’t say about the true scale of its gun violence.

The Twist in the Chicago Murder Narrative

If you watch the seasonal ebb and flow of homicide numbers in Chicago since 1957, as the Chicago Tribune did recently, you see how violence flares in the summer, then retreats every winter. Pull further back and the six-decade saga—39,000 killings, by the paper’s count—seems to assume a three-act structure, dominated by a ferocious second-act stretch from 1969 to 1998 in which the annual toll topped 650, peaking in 1992 with 943 killings.

Then comes a slow decline during the 2000s and 2010s, with a low of 415 total homicides in 2014. The last two years form a troubling coda. As violence surged, sank, and spiked anew, law enforcement officials and local politicians were quick to claim the credit—and then get hammered with the blame.

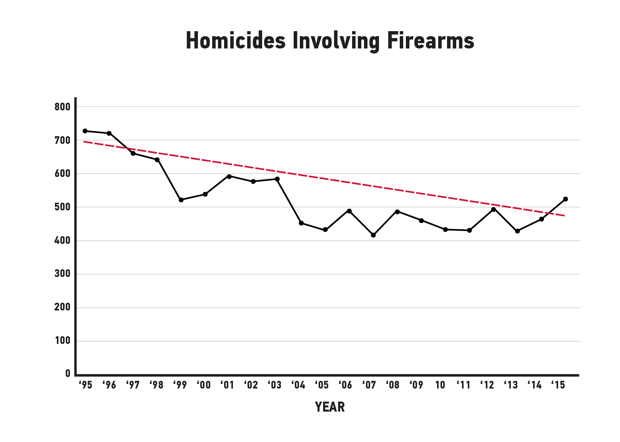

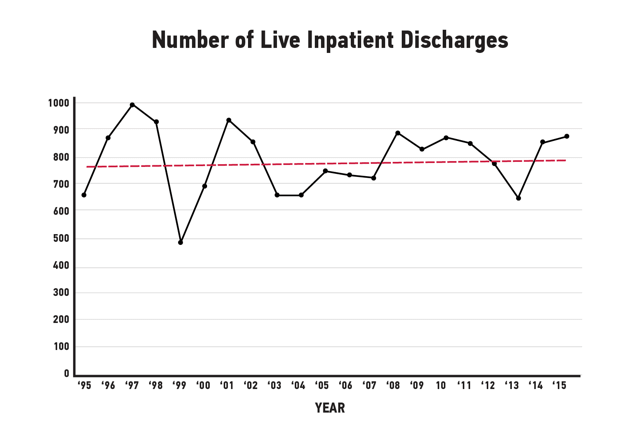

But telling the story of gun violence in Chicago only through the rise and fall of the Chicago Police Department’s homicide stats misses another narrative entirely. To see this, reporters from Chicago’s Data Reporting Lab looked at homicide and shooting data covering Cook County, which contains the city of Chicago. These figures from the Illinois Department of Health and official Chicago police statistics reveal not only the number of gun-related homicides but also the number of patients discharged from county hospitals with gunshot wounds from 1990 to 2015.

The narrative they tell is a slightly different one: As murders trended down overall, the number of shootings has been holding relatively steady—and even scaling up.

(Chart: Data Reporting Lab/CityLab)

Take 1995, when guns accounted for 73 percent of all homicides in Cook County. There were 995 total slayings. Fast forward to 2015, and there were 604 killings, with guns accounting for a larger proportion—84 percent—of them. The homicide toll during that 20-year span was lowest in 2013: 536 killings, with guns making up 80 percent of them, or 430 homicides.

But while homicides by firearms went down over that stretch—by 30 percent overall—shootings do not appear to follow the same pattern. The annual number of Chicago-area gunshot victims who survived and were discharged from the county’s hospitals bounced up and down, starting with 677 in 1995 and ending at 870 in 2015, according to hospital inpatient discharge records.

(Chart: Data Reporting Lab/CityLab)

In other words, the story of Chicago’s lower homicide rates during the 2000s and 2010s doesn’t seem to be intimately connected to law enforcement tactics, as city leaders and police officials often suggest.

During the years when homicide was in decline, police regularly touted new programs and legal strategies that were used to lop the head off the gangs that bloodied the streets of Chicago for generations. It was an easy sell: More community policing, hit the hotspots of drug dealing and gun trafficking, and use random stops to clear out cars of drugs and weapons. But that explanation came unglued after 2015.

The Chicago Police Department and the Mayor’s Office did not respond to requests for comment. But current Chicago Police Superintendent Eddie Johnson has cited new policing strategies and tactics as the chief reason the slayings dropped by more than 100 in 2017. “The fact that we’ve got it over 100 in terms of reduction is really room for encouragement and positive thinking going into 2018,” Johnson told the Tribune, which uses a different methodology for calculating homicides in Chicago: Their calculations bring the 2017 toll up to 670, which includes slayings on expressways (which are patrolled by state police).

It’s also worth noting the period covered in this analysis was a turbulent one for the Chicago Police Department, which saw a turnover of several superintendents and was the target of a scathing Department of Justice investigation in 2015. As crime surged in that year, Mayor Rahm Emanuel remarked that the department had gone “fetal” in their policing tactics in the aftermath of controversial police shootings, a comment that drew fierce opposition from officers and contributed to the national debate around the “Ferguson effect” and its possible role in explaining crime upticks in several U.S. cities.

Other first responders might be less surprised by the relationship between policing, shootings, and homicides.

“Everyone knows it’s the fire department that saves lives in Chicago,” said one high-ranking Chicago Fire Department official who declined to be identified, “not the police.”

It’s a distinction that the city’s policymakers should heed. “It’s not really the murder rate but the shootings that we ought to be looking at,” said Toni Preckwinkle, president of the Cook County Board of Commissioners and a former alderman representing the South Side’s Fourth Ward. “The world-class nature of our trauma care masks, to some extent, the problem. … Looking at the gun violence issue as simply a policing issue is a terrible mistake.”

“Shifting the Spectrum”

In a way, there’s a remarkable medical success story buried in this data. “People that would have died are now surviving with disabilities, and people who would have survived with disabilities are now surviving with a full recovery,” said John Barrett, former director of the trauma unit at John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County. Trauma specialists “are shifting the spectrum backward. The end result is that less people are actually dying of those who were shot.”

But to Mary Sheridan, the city’s chief paramedic, this is an achievement laced with tragedy. “It’s sad that our paramedics are great at what they do,” she said. “Navy and Army medics are training at Rush [Medical Center], and they ride with us. It’s sad that they should be getting that kind of experience on the streets of Chicago.”

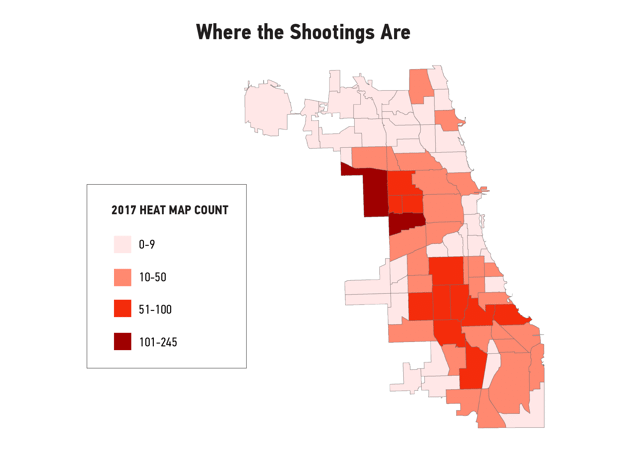

Chicago’s success as a national leader in trauma care also has a stark geographical limitation, one that community members have long sought to address. The vast majority of Chicago slayings—94 percent in 2017—occur in the city’s South and West sides, in places marked not only by poverty but, in some cases, a lack of swift access to medical care. The southeast corner of the city marks a perilous “trauma desert,” where shooting victims are often shuttled out of the city to suburban centers, or north to Stroger Hospital near downtown. It can be a deadly delay.

(Map: Data Reporting Lab/CityLab)

That will soon change: 25 years after closing its trauma facility, the University of Chicago broke ground on a new trauma center in September of 2016. The estimated $43 million facility is set to open in May, after years of protests and pressure from the South Side community. According to Sheridan, the University of Chicago trauma center is expected to have “a significant impact” on survival rates. “Our ambulances may have a seven- to 10-minute ride, versus 20 minutes. The times are going to fall by half or better.”

Those minutes can be critical. In emergency care, the concept of the “golden hour” following severe injury—a bedrock principle of the field since the 1970s—emphasizes the urgency of getting victims to hospital care. Transport time is particularly critical in cases of penetrating wounds like gunshots, where severe blood loss makes every moment count. But, according to research from Dr. Marie Crandall, a trauma surgeon and former Northwestern University Hospital associate professor of surgery, more than a quarter of shooting victims from parts of southeast Chicago experience transport times of 30 minutes and up. If you take a bullet in front of UChicago hospital today, you might have to take a ride north to Stroger before receiving hospital care, losing precious moments.

“For every mile away [that] a gunshot victim is from a trauma center, there’s an increase in the mortality rate,” said Crandall, now professor of surgery and director of research at the University of Florida College of Medicine Jacksonville. “We found that people shot more than five miles away from a trauma center door increased the risk of dying more than 23 percent.”

Besides time, the men and women trying to save Chicago’s shooting victims are racing another enemy: the growing lethality of modern weaponry. “There has been this drastic increase in the number of gunshot victims we’ve been seeing over the last two years—but also, we are seeing an increase in the number of wounds,” said Dr. Ponni Arunkumar, Cook County’s chief medical examiner. “Before we’d see gunshot victims with maybe two or four gunshot wounds. Now we see victims with eight to 10.”

Semiautomatic weapons like the AR-15—the rifle used in the Parkland, Florida, school shooting this month—are becoming a more common tool in the arsenal of some gangs in Chicago. Last year, an AR-15 was recovered after the shootings of two Chicago police officers. The rifles shoot high-velocity bullets that can be vastly more damaging than bullets fired from typical firearms. Arunkumar also cites the destructive nature of so-called R.I.P bullets (for “radically invasive projectile”), a type of hollow-point round designed to fragment inside a person’s body, in order to cause maximum trauma. Their manufacturer markets them as “the last bullet you’ll ever need.”

When shooting victims in Chicago started turning up with these wounds, “we didn’t know what we were dealing with,” Arunkumar said. “We had to look it up. Then we looked up the casing and the kind of projectiles and how they produce injury.” What they found was frightening. “Once it impacts the soft tissue, it fragments and goes in different directions. One surgeon described it to me as like little paper clips.”

Essentially, Chicago’s world-class trauma system is deadlocked in a kind of technological arms race, with first responders deploying the latest combat-proven gear and techniques against weaponry on the streets that has become more lethal. Given this escalation, the current survival rates of Chicago’s shooting victims stand as an even more impressive achievement. But it has come at a daunting cost—and it can’t be sustained indefinitely.

Stopping the Bleeding

Start with the costs to the city of dispatching a fully loaded ambulance. Each new vehicle costs the city up to $400,000; to fully staff and equip it runs the bill to around $2 million, per ambulance, per year, according to city officials.

Then add the costs of surgery to repair (if possible) the victim’s wounds and the weeks and months of aftercare and rehabilitation. In Chicago alone, a study from the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab in 2009 estimated that the costs associated with shootings total $2.5 billion annually—a staggering figure that factors in “lost worker productivity, medical costs, mental health costs, and costs to the government vis-à-vis the criminal justice system,” the study authors wrote. The same study concluded that the national figure was $100 billion. In 2015, Mother Jones ran the gun violence bill for 2012 up to $229 billion; that figure included $169 billion worth of impact on victims’ quality of life and $49 billion in lost wages.

But there’s considerable guesswork in such figures, as the issue has been only lightly researched, and estimates are all over the fiscal map. Consider: A Johns Hopkins study found last year that the yearly total for hospital costs associated with gun violence as just under $3 billion nationally. And a Chicago Tribune analysis last year showed Chicago-area hospitals and trauma centers got a $447 million bill covering the care of about 12,000 victims between 2009 and the middle of 2016.

Part of the explanation for the varying public-health costs related to gun violence is that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—the very government entity charged with studying and tracking what ails Americans—has been effectively blocked from funding research on the topic since 1996, when the GOP-led Congress threatened to strip CDC funding over the issue. In the wake of the Parkland shooting, calls to reverse that have intensified recently.

To stanch this bleeding of dollars as well as blood, Sheridan advocates a model known as community paramedicine, which is currently being used in a few pilot areas in Chicago. That model integrates emergency response with primary care; it connects 911 dispatchers, social workers, nurses, EMTs, paramedics, surgeons, cops, firefighters, and after-care specialists to provide a coordinated “continuum of care” throughout a longer period of time—and identify problem patients and hot spots earlier. “It’s a whole change of the health-care system,” Sheridan said, “and a wild change to the billing system would have to take place. Because, as it is, the cost to the city is too huge.”

Especially in low-income neighborhoods, emergency responders now tend to function as an extremely costly form of primary care. Community paramedicine would allow first responders to intervene in troubled areas earlier, providing care on the spot instead of making unnecessary ER runs. “What do you say to the elderly woman who wakes up scared and lonely and calls 911?” Sheridan said. “We could put 50 more ambulances on the streets of Chicago, but if we’re not using them appropriately, it won’t make a bit of difference.”

The Chicago Fire Department has studied community paramedicine in Rockford, Illinois, and Minnesota, as well as several pilot areas of the city. Sheridan said the department and others are working to keep in closer contact with any victim or patient after release, to better keep tabs on their health and ward off re-victimization. “This is not just Chicago, but a national focus,” she said.

Not long ago, Sheridan and others went to Washington to lobby on behalf of this model. “I think we had everyone’s ear, but the changes from Obamacare to Trumpcare to whatever is coming has pushed it back months, if not years.”

So, for now, Chicago’s first responders will keep running their race with gun violence, doing what they do to keep a lid on the city’s murder rate. There’s a limit, however, to what even the most well-equipped trauma centers and the most advanced emergency care technology can achieve without more social and political willpower. “We have not done anything to alter the root causes of violence in those communities,” said Loyola’s Lurigio. “We need to change the climate. Climate change takes a very long time.”

And in Chicago, that hasn’t happened yet. Winter here is often a time when harsh weather offers a respite from the killing; so far, 2018 has failed to provide much of a pause. In the first week of February, Cook County Board president Toni Preckwinkle checked the numbers.

“As of Monday of this week,” she said, “we’ve already seen 51 gunshot homicides in the [medical examiner’s] office.”

With additional reporting by Kevin Stark of the Data Reporting Lab. This story is part of a collaboration between CityLab, The Data Reporting Lab, and Reveal, a podcast from The Center for Investigative Reporting and PRX. To listen to the full episode, go to revealnews.org/podcast.

This story originally appeared on CityLab, an editorial partner site. Subscribe to CityLab’s newsletters and follow CityLab on Facebook and Twitter.