For someone with as long a list of enemies as President Donald Trump—a guy who once dedicated his New Years wishes to his many haters—it says something that American media tops the list. Epithets like “Little Marco” and “Crooked Hillary” marked his candidacy, but since taking office, the standout slur is the all-purpose one that he uses against journalists: “Fake News.”

During his first year in office, Trump averaged more than a daily use of the word “fake,” a CNN analysis of his tweets found, and while his use of the word “fake” was occasionally applied to such things as the Russia dossier, it was almost always directed at the news media as an insult.

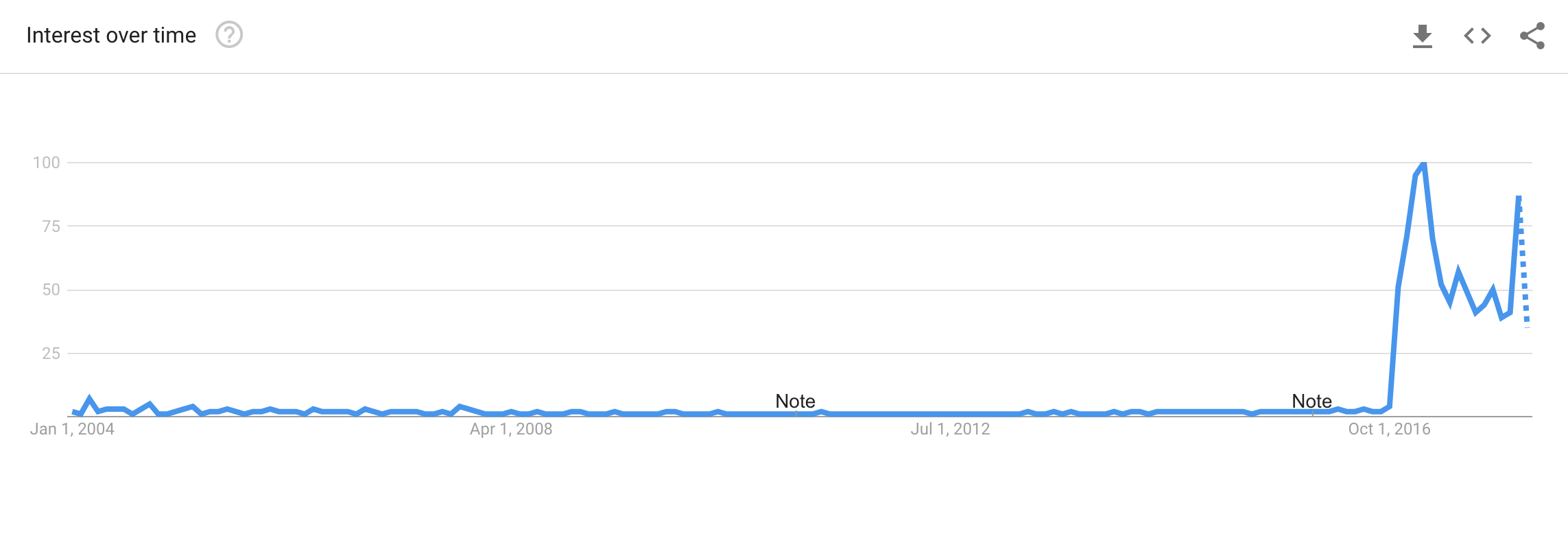

Over time, examples of the phrase have popped up here and there, but Google Trends shows it didn’t become commonly cited until Trump essentially made it so:

“Fake news” was dubbed the “Word of the Year” for 2017 by the Collins Dictionary, which found that the term’s usage had risen by 365 percent since the 2016 election. But if Trump helped popularize the misuse of the term, he didn’t invent it.

During the 2016 campaign, “fake news” was used to describe actual fabricated news stories from websites that publish hoaxes, as well as from hyper-partisan websites purporting to offer real news. Some of those stories—including false scoops about Pope Francis endorsing Trump and Hillary Clinton selling weapons to ISIS—went viral on Facebook in the final months of the election. Overwhelmingly, the stories tended to favor Trump.

Such revelations might have been used to question the legitimacy of Trump’s electoral win, but once elected, Trump weaponized the term, turning its meaning on its head. Instead of using it to describe a specific corrupt phenomenon (which, again, overwhelmingly aided his candidacy), he used it to discredit the non-fake news sources that might keep his power in check. With the help of his 48 million Twitter followers and the most powerful political platform in the world, his campaign to transform “fake news” into an all-occasion put-down has worked, at least by some measures.

Now, “fake news” can refer to biased media, editorial malfeasance, spurious content produced overseas for profit, or simply any news Trump doesn’t like—depending on who’s listening.

A majority of Americans now think “fake news” poses a threat to democracy, according to a recent Gallup-Knight Foundation survey; they just can’t agree about what that actually means. And what they think it means varies by political persuasion.

There is no evidence that real news outlets have become radically more inaccurate, for instance, but the survey found that 42 percent of Republicans now consider any news critical of a politician to be “fake news.” (Yes, you read that right.)

Meanwhile, research from Dartmouth College’s Brendan Nyhan and others has found the reach of fake news to be wide but shallow: During the election, only a subset of Americans visited fake news websites—websites promoting faux election stories—and most were likely exposed through Facebook in a glancing way.

What’s more, the promotion of fake news stories online is just one part of a larger social media-fueled phenomenon some call “information disorder.”

Such worthy concerns have become little more than a footnote in a larger hysteria around traditional media, however, fueled by Trump’s obsession with demonizing those who report on him.

Of greater concern than the drivel promoted at the margins of social media is how Trump has used its existence to say that everything is broken. Just as he tapped into people’s fears of joblessness or anger at feeling displaced in their own country, Trump has exploited fear and uncertainty around the media for his own political advantage.

In doing so, he’s already done much more to disrupt and obfuscate the flow of truthful information than anything spread by some spurious websites on Facebook.

A Brief History of Fake News and Its Political Exploiters

Fake news, broadly defined, has been around a long time, as a thumbnail history by the Columbia Journalism Review shows.

One of the best-known hoaxes occurred in 1938, when Orson Welles’ portrayal of a Martian invasion, which aired on CBS, incited widespread panic in listeners who missed the initial disclaimer that the segment was not news but a live radio drama.

Then as now, the panic stemmed not so much from the content itself, but rather from perceptions about the medium. As Benjamin Naddaff-Hafrey has argued in Pacific Standard, public anxiety over War of the Worlds centered on “notions of aural suggestibility that made an imaginative radio play the focus of extraordinary popular concern.” In other words, then, as now, the panic over “fake news” outweighed the actual problem.

Among the most high-profile examples of fake news in modern American history involved the retraction of a Pulitzer Prize awarded to the Washington Post‘s Janet Cooke in 1981, when her story about a child heroin user was found to be fabricated. It was a shocking revelation, particularly coming under the nose of the same editor who had led the Post‘s heroic coverage of Vietnam and Watergate. And while we don’t know just how much damage Cooke’s story did to the country, its pernicious effect on Americans’ perceptions of media are clear: More than 30 years later, overall trust in the institution has not recovered, research indicates.

Politicians have used such distrust to their advantage—and not just recently: For as long as there’s been fake news, there have been those who’ve sought to capitalize on it politically.

There’s the term Lügenpresse (“lying press”), which found an audience in Nazi-era Germany, among other places. And there’s Joseph Stalin’s “vrag naroda” (“enemy of the people”) language, used to encompass a broad array of opposition, which Trump has co-opted and applied to media. Trump even seems to have inspired a few foreign dictators himself: A Google trends map of “fake news” under the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte parallels the term’s use in the U.S., and a Politico review demonstrates that leaders and state media in at least 15 countries use the phrase to dismiss critics.

The Founding Fathers expressed concern about “fake news” too. In 1807, then-President Thomas Jefferson wrote, “It is a melancholy truth, that a suppression of the press could not more compleatly [sic] deprive the nation of its benefits, than is done by its abandoned prostitution to falsehood. Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper.”

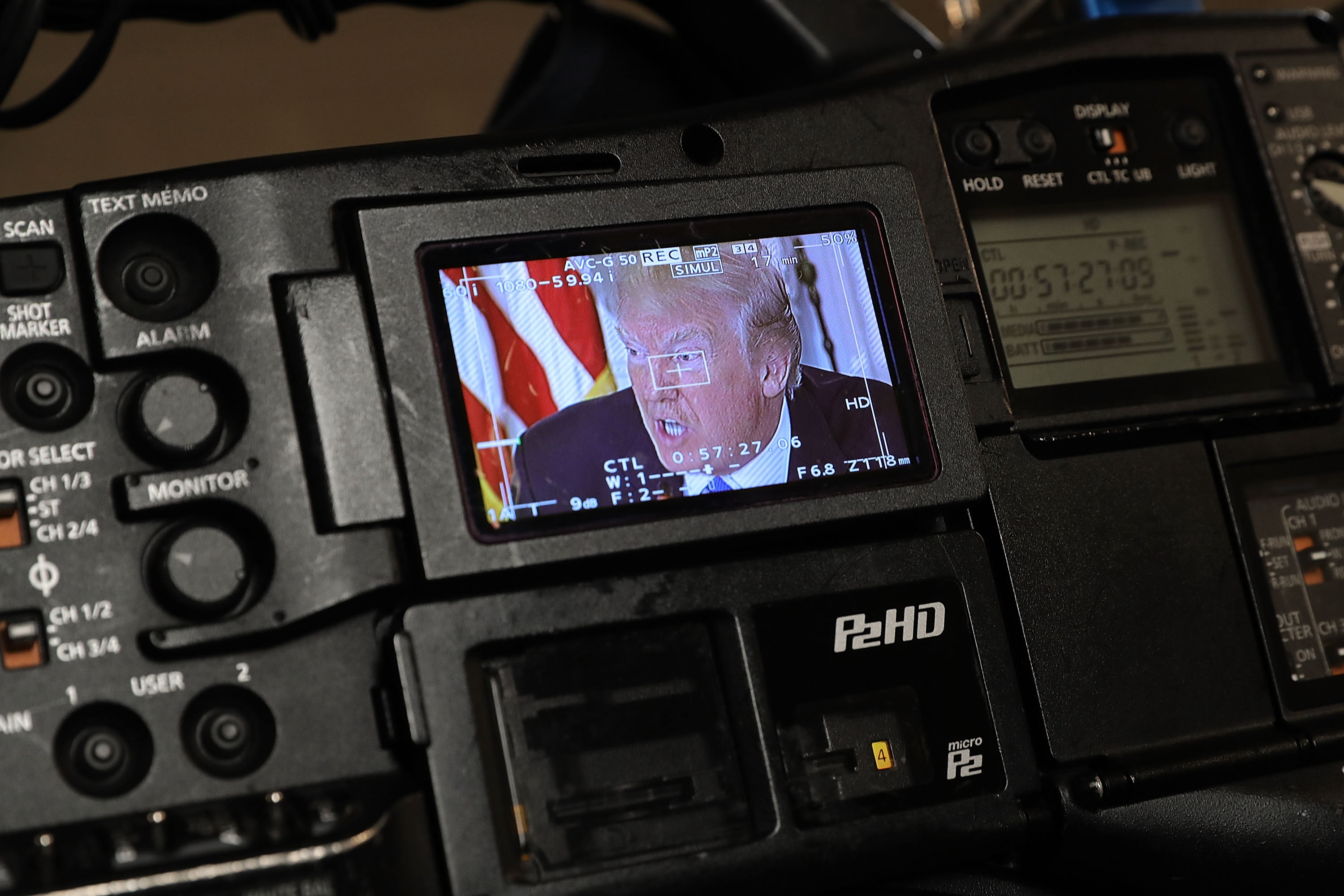

(Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Yet the modern press, which strives for evenhandedness, bears little resemblance to what Jefferson saw. “In the 1800s, you had editors who were party operatives and papers written solely to whip up the crowd,” Mark Feldstein, a journalism historian at the University of Maryland, tells me.

“That’s different from the kind of notion that Trump has spread, and that’s spread on the right. That is a malicious, deliberate, demonic kind of falsification for political purposes,” Feldstein says, adding, “that’s a relatively new and insidious development.”

As Nyhan tells me of Trump: “He’s certainly not the first politician to attack the media. But in contemporary American politics, we’ve never seen a president go after the media so frequently and with such vitriol. ‘Fake news’ is one version of that that is potentially the most damaging.”

The Biggest Lie of Fake News

The birth of “fake news” as we know it can be traced to January of 2017, when Trump used it to dismiss tough questioning about his ties to Russia. But the political theater reached new heights in January of this year, when—having parlayed racist conspiracy theories about America’s first black president right into his seat at the White House—Trump decided he should play high judge to accuracy in reporting with his “Fake News Awards.”

Vocally hyped, then subsequently delayed, then downgraded to a “potential event,” it amounted to little more than a rehash of the president’s old Twitter gripes. Many of the stories singled out were indeed inaccurate but had been duly corrected, with serious repercussions for journalists who erred.

If the stories had a commonality, it was how few of them—be they about crowd size at a rally or a handshake with the Polish first lady—could be said to matter at all. And if they underscored anything, it was how little of the most consequential disinformation was actually disseminated by the outlets that Trump likes to attack, as well as how little of it had anything remotely to do with editorial malfeasance.

As with nearly any point in American history, the most damaging misinformation has come from the people whose power the press exists to check.

Consider how the Nixon administration misled the public around the Vietnam War—lies paid for in the flesh and blood sacrifice of American soldiers. Then consider Trump’s “Fake News Awards,” which among other things focused on whether he had overfed some fish in Japan.

At times, the president’s “fake news” circus can feel frivolous—but it’s not. And what his whole phony fixation with “fake news” threatens to distract us from is that the violence of what he’s suggesting is only just barely under the surface. He has called for the jailing of journalists and kept them cordoned off in pens during his campaign rallies. In January, when a teenager called up CNN and threatened to gun down everyone at their “fake news” headquarters, nobody had to ask where he’d gotten that notion.

No One Agrees What Fake News Is (or What to Do About It)

Even the dictionary doesn’t know how to define fake news. In Dictionary.com’s next update, the online reference will add a definition for “fake news,” Time has reported, but the proposed definition ignores crucial political context, offering: “false news stories, often of a sensational nature, created to be widely shared online for the purpose of generating ad revenue via web traffic or discrediting a public figure, political movement, company, etc.” The move has been described as part of the dictionary’s commitment to neutrality, but it’s hard to ignore that it’s precisely the definition Trump would want in the dictionary. (In an email, Dictionary.com’s Jane Solomon tells me, “we’re closely monitoring developments in meaning of this term, and we’ll make changes to our entry if that’s where our research leads us.”)

Similarly, students at top high schools around the country have whole courses dedicated to media literacy, so they can differentiate real news from fake news online. But who will teach them about how Trump has politicized “fake news”?

Perhaps it’s telling that Craig Silverman, the BuzzFeed reporter whose investigative reporting on Facebook helped ignite the conversation around “fake news,” has offered a mea culpa for his role in popularizing the term. “I should have realized that any person, idea, or phrase—however neutral in its intention—could be twisted into a partisan cudgel,” he wrote.

That’s why some critics, like Claire Wardle—a research fellow running First Draft, a project of the Shorenstein Center at Harvard University’s Kennedy School—have abandoned the term “fake news” entirely, even as she strives to tackle the real problems of information pollution online.

“The reason I don’t like the phrase now is it’s used as a term to describe everything,” Wardle told the BBC. In a widely shared 2017 paper for the Council of Europe, “Information Disorder,” Wardle and her team lay out some more precise terms, which account for the intent of the speaker or author in differentiating between “mis-information,” “dis-information,” and “mal-information.” They also offer suggestions for how technology companies, government actors, and others can work toward solutions.

In the short term, the outlook for solving the real problem, specifically one that’s enabled by companies like Facebook, is grim: The Facebook-friendly Trump administration has already knee-capped regulators. And there’s little reason to think companies for whom profit is king will do all that’s necessary to self-regulate, though recently Facebook has promised some changes.

Even on the most basic front—defining the terms of the “fake news” conversation—experts face a wall: Few things carry farther than Trump’s Twitter feed, after all, and the fast pace of online information makes it hard for nuanced definitions to break through.

That means even the relatively simple task of illuminating the greater issue—how Trump is exploiting the situation to sew distrust in the institution of media, and experts everywhere—will continue to be an uphill battle.

As with anything, the first step in solving a problem is recognizing that you have one—and false reports about fish feeding aren’t it.