Since his 1991 book There Are No Children Here, Alex Kotlowitz has worked as one of the most in-depth chroniclers of urban American life. Kotlowitz is a documentarian (The Interrupters), a broadcaster (a This American Life segment on Harper High School), a journalist (he’s contributed to the Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker, and others), and an academic (he teaches a course in “The Journalism of Empathy” at Northwestern University).

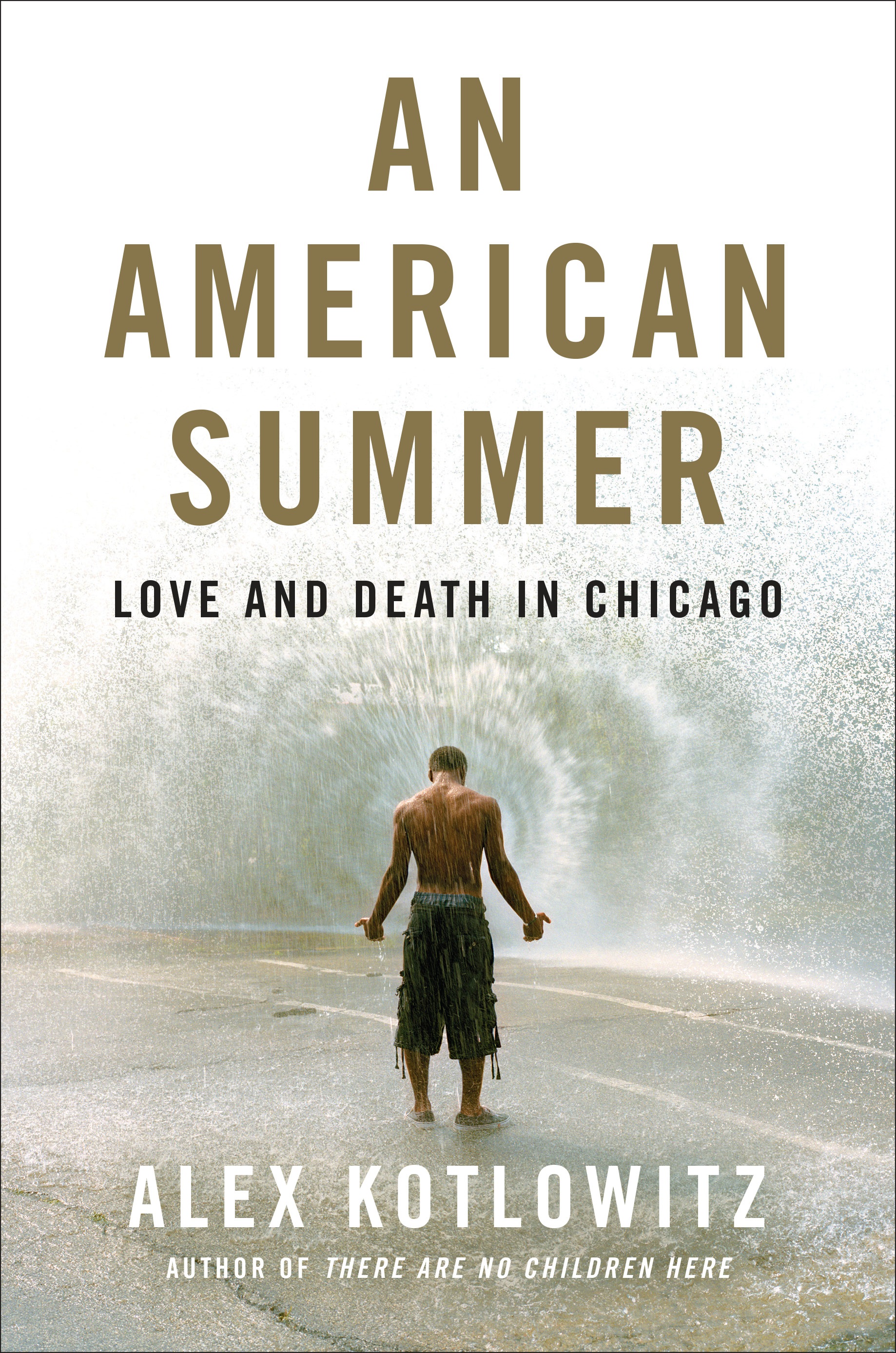

Kotlowitz’s new book, An American Summer: Love and Death in Chicago, is a beautifully written, nuanced, and empathetic book about tragedy, courage, and heartbreak in Chicago during the summer of 2013. In the introduction, Kotlowitz describes the book as “a set of dispatches, sketches of those left standing, of those emerging from the rubble, of those trying to make sense of what they’ve left behind.” Describing the violence of the summer of 2013 in Chicago, Kotlowitz writes: “Over the course of three months [that summer], 172 people were killed, another 793 wounded by gunfire.” An American Summer tells the story of “how, despite the bloodshed, some manage, heroically, not only to push on but also to push back.”

Kotlowitz says he hopes that Chicago communities like Englewood and North Lawndale, and families like Ramaine Hill‘s, will begin to receive the same kind of national attention and sympathy that communities such as Newtown and Parkland have received after tragedies in those places.

“It’s in these, the most ravaged of our communities, among the most desperate and forlorn, that we can come to understand the makings of who we are as a nation,” Kotlowitz says.

Kotlowitz spoke with Pacific Standard to discuss gun control, the uses of empathy, and what he loves about Chicago.

There’s a moving scene in your and Steve James’ classic documentary The Interrupters when Ameena tells Caprysha, “You gotta love yourself first.” Is that a lesson people might take from your new book?

That moment stayed with me, the notion that people are searching for a sense of respect, a sense that they belong, a sense that they matter. That is certainly something I saw in the people I spent time with for An American Summer. One of the consequences of the violence is that people often feel utterly alone, certain that no one could possibly understand what they’ve experienced. There’s a moment in the book when Nijajuan Hill, who has lost his brother Ramaine, tells me, “It’d be nice to speak to someone who’s been through the same thing. Nobody understands. … It’s like I feel nobody cares.” That sentiment was echoed by so many. They were just looking for validation of the sorrow and the grief they carried with them.

What is the central moral question of An American Summer?

In these stories, as people emerge from the violence and try to reckon with it, they grapple with notions of forgiveness and justice, two notions central to the American character. We like to think of ourselves as such a forgiving country, and yet we can be terribly unforgiving, especially when it comes to people who are struggling, who have been pushed along the margins. And justice, of course, is a central underpinning of our nation—and yet spend time in these communities and it’s clear that life is not just; that life is not fair. What does that say about us as a nation, that reality falls so short of our aspirations?

(Photo: Kathy Richland)

What can An American Summer tell us about the future of Chicago policing and about race relations in the city?

There’s one story in the book that left me reeling with anger: the shooting death of a young man, Calvin Cross, by the police. There are so many questions around that shooting, not the least of which is, it appears the police officers lied under oath when recounting the events of that evening. They were not only not held accountable, but were awarded merits of valor. Trust between the police and communities of color has eroded significantly in recent years, especially after the shooting death of Laquan McDonald, which happened the summer after the one in the book. Much of the tension, I believe, stemmed from the War on Drugs, which even by its rhetoric—this notion that we were “at war”—suggested there was an enemy out there.

I’m hopeful, though. There’s now a consent decree in place, and the two candidates for Mayor both have talked firmly and candidly about the need to shape a police force that sees itself aligned with these communities and not in battle against them.

What were the surprising elements you found while reporting the book? What might surprise readers?

I knew going in that the terrain—writing on violence—was rather grim. But I came away in awe of many of the people I write about. Most are standing erect in this world slumping around them, and some of them are moving forward, heroically, pushing back. Some of the stories, indeed, are heartbreaking; but I found so many of them to be inspiring, not only in the fortitude of the people in these pages, but also in their capacity to forgive and to love.

“The guns come up from the South,” Steve James [Kotlowitz’s co-director for The Interrupters] once told me, speaking about gun control. “From any number of states where there are no real gun laws. Until this country decides—if this country decides—to really tackle it on a much broader level nationally, it’s always going to be hard to really make meaningful impact on that issue because it’s too easy to bring guns across state lines and into cities,” he said. Do you agree? How might we limit access to guns in Chicago?

(Photo: Nan A. Talese Books)

That’s right. Chicago is surrounded by states, especially Indiana, with weak gun control laws. And so while the city has put reasonably tough restrictions on gun ownership, it means little if you can drive just an hour to a state where you can easily purchase guns. Every year, the police take off the streets 7,000 to 10,000 illegal guns. Every year. It’s this constant river, and there’s no cutting off that supply until we have some kind of national movement toward tightening gun ownership. It seems so reasonable. I’m not talking about eliminating gun ownership, but I am talking about regulating it so that, as best we can, we ensure that those who have guns don’t mean harm. It seems so common sensical, but of course we have the National Rifle Association to contend with, an organization that appears to lack much common sense.

You have a passion for fairness, for untold stories about the marginalized. Can you talk about one of your main influences: fellow Chicagoan Studs Terkel?

Studs was a mentor and a good friend. He recognized the poetry in the lives of everyday people. He saw what others didn’t. He told the stories of those who were struggling but persevering—individuals who were deeply reflective, who saw things others didn’t see, who asked questions the rest of us stopped asking. Moreover, central to Studs’ work was this rather simple notion that life ought to be fair. Hanging above my desk is something Studs once said:

My goal is to survive the day, to survive it with a semblance of grace, curiosity, and a sense I’d done something pretty good. I can’t survive the day unless everyone else survives it too. I live in a community and if the community isn’t in good shape, neither am I.

What do you love about Chicago?

I love the city for its people, for its messy vitalities. Through my reporting, I’ve made these lifelong friendships that have made my life and my family’s life so much richer. It’s also America’s city, a place where you can find all the fissures in the American landscape within the confines of the city. So many stories to tell. So many stories that need telling.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.